Moment's Notice

Recent CDs Briefly Reviewed

(continued)

Tony Malaby

Paloma Recio

New World Record 80688-2

“Paloma Recio” translates as “loud dove” and it’s both the name of the album and the name of the band, a quartet in which Tony Malaby is joined by guitarist Ben Monder, bassist Eivind Opsvik, and drummer Nasheet Waits. There’s also a tune called “Loud Dove,” a densely polyrhythmic exchange that demonstrates the band’s penchant for both a keening lyricism and dense collective improvising. It suggests how central the phrase is to Malaby’s conception of the band. The name may not indicate contradiction exactly, but emphasizes a union of the unlikely, whether it’s the coexistence here of both a gentle lyricism and a certain force or, further, the complex relationship between improvisation and composition that the group explores. Malaby has described this as “new music dedicated to an angel flying over the Iberian Peninsula by a new quartet of omni-directionally improvising masters of ecstatic lyrical elasticity.” Hear the CD; you’d likely forgive him what might seem excessive: Paloma Recio (the CD) communicates almost instantly a sense of shared values and high achievement, as well as a certain fulsomeness. Malaby sticks to tenor saxophone, a central and unifying voice, and the band plays together with a rare intimacy, the listening so close that the four often exchange sonorities, bass passing into drums, guitar into tenor, guitar and bass into each other. That’s rare enough in texturally-oriented free improvisation, but Paloma Recio (the band) is usually playing strongly linear music.

“Paloma Recio” translates as “loud dove” and it’s both the name of the album and the name of the band, a quartet in which Tony Malaby is joined by guitarist Ben Monder, bassist Eivind Opsvik, and drummer Nasheet Waits. There’s also a tune called “Loud Dove,” a densely polyrhythmic exchange that demonstrates the band’s penchant for both a keening lyricism and dense collective improvising. It suggests how central the phrase is to Malaby’s conception of the band. The name may not indicate contradiction exactly, but emphasizes a union of the unlikely, whether it’s the coexistence here of both a gentle lyricism and a certain force or, further, the complex relationship between improvisation and composition that the group explores. Malaby has described this as “new music dedicated to an angel flying over the Iberian Peninsula by a new quartet of omni-directionally improvising masters of ecstatic lyrical elasticity.” Hear the CD; you’d likely forgive him what might seem excessive: Paloma Recio (the CD) communicates almost instantly a sense of shared values and high achievement, as well as a certain fulsomeness. Malaby sticks to tenor saxophone, a central and unifying voice, and the band plays together with a rare intimacy, the listening so close that the four often exchange sonorities, bass passing into drums, guitar into tenor, guitar and bass into each other. That’s rare enough in texturally-oriented free improvisation, but Paloma Recio (the band) is usually playing strongly linear music.

There’s a consistent focus on process here as well, a subliminal source of much of the musical dialogue. The intense and sustained “Alechinsky” employs graphic notation, while a series of relative miniatures are freely improvised, each initiated by a pairing with Malaby: “Hidden,” almost in undertones with Waits; “Boludos” a gritty sonic exploration with Monder prominent; “Puppets,” building from Opsvik’s minimal trailing line to the tenor saxophonist. That sense of process finds intriguing completion when the CD concludes with a straight “reading” of the melody of Federico Monmou’s “Musica Callada.” According to Mark Helias’ notes, Malaby drew the themes from improvisations recorded by another of his groups, the trio Tamarindo with William Parker and Waits, and there’s a sense here of Malaby’s concentration on the discovery of the kernel musical gesture and its amplification in the new contexts of both composition and the different group. There’s a sense in which Paloma Recio feels like an instant masterpiece, an inevitable consequence of the sheer brilliance of its surface. But there are some genuine depths here as well.

–Stuart Broomer

Rob Mazurek Quintet

Sound Is

Delmark DE 586

Forty years after Kind of Blue, this stakes some claim to being a new Zeitgeist record. It’s a trumpeter’s record, in a relatively conventional “jazz” format, though with a somewhat different instrumentation, and it’s just about easy enough on the ear to put on and forget. Just about, though I wouldn’t recommend it, for Mazurek’s deceptively restless eclecticism and unabashed appetite for lyricism-in-chaos hides an iron-hard conception, and even tougher – would that be tungsten-hard? – chops.

Forty years after Kind of Blue, this stakes some claim to being a new Zeitgeist record. It’s a trumpeter’s record, in a relatively conventional “jazz” format, though with a somewhat different instrumentation, and it’s just about easy enough on the ear to put on and forget. Just about, though I wouldn’t recommend it, for Mazurek’s deceptively restless eclecticism and unabashed appetite for lyricism-in-chaos hides an iron-hard conception, and even tougher – would that be tungsten-hard? – chops.

He’s not featured as a cornet player on the opening cut, “As If An Angel Fell From the Sky,” at all. It ascends in a shimmer of synth patches, softly chiming vibes from Jason Adasiewicz, and other less clearly provenanced sounds. Then, a palpable surprise as “The Earthquake Tree” relaunches the record in a post-bop direction, its descending hook maddeningly familiar: it wouldn’t be out of place on a classic era Miles quintet LP or one of Shorter’s more accommodating Blue Notes. Nobody was hitting drums in those days like Tortoise man John Herndon does here, and Ron Carter only later got the idea of playing electric bass like Matthew Lux does, heavy and subtle.

It’s interesting at this point to flip to the “Other Delmark albums of interest” strap under the CD. If you like this, they’re saying . . . you might want to try not just Mazurek’s work with the Chicago Underground Trio or his solo 2002 Silver Spines for the label, but also Sun Ra’s Sun Song and Sound of Joy, NRG Ensemble’s This Is My House, Braxton’s For Alto and Roscoe Mitchell’s Sound Is. The last of these is – surely deliberately? – referenced in this record’s title. At first blush it’s hard to detect any lineage, but by the time you’re thinking that, you’re likely be a couple of minutes into “Dragon Kiss.” a swirly, nasty, abstract/urban thing that rattles and thuds away under Mazurek’s declamatory horn line. It’s one of those pieces that is instantly hard to date. Sure, some of the AACM guys were doing things like this back in the day, but there’s something about the soundworld that won’t work for the late 60s.

Mazurek’s in São Paulo now and it’s clear that his musical orbits are as various as they are different from any of the Chicago “schools.” There’s no immediately evident “Latin” or “world” element, until you listen to the way the rhythms drive a line that turns out not to be a line at all, but a series of discrete episodes in sound that drift ambiguously over the rhythms. “The Star Splitter” starts out like an off-cut from one of Miles’s Warners sessions, except for the chiming piano; Josh Abrams doubles keyboard and bass. This time the drums have given place to an insistent metal chime and what threatens to turn into a shuffle but never does. It’s edgy, oddly disturbing music, and even the reassuringly processed horn on top doesn’t soften the impact.

We’re still not half an hour into a set that has another 45 minutes or so to go, but it’s becoming clear from casually repeated figures and allusions that Sound Is can most effectively be regarded as a continuous performance, not in the bland, faux-perceptive way that a row of tracks is revealed to be ‘really’ a suite, but in that this group’s conception is so self-defined and self-confident and its focus on the present material so complete that you’ll never hear music like this again.

As for the rest, “Le Baiser” (helpfully glossed as “The Kiss.” but oh, so much more!) is a minxy little number, a jazzers’ “Bolero” and the record’s most explicit nod to Miles. By contrast “Microraptagonafly” suggests recent (re)acquaintance with Dolphy, who Miles couldn’t listen to without pain. “Beauty Wolf” doesn’t quite come off, but “Aphrodite Rising,” “The Lightning Field” and “Cinnamon Tree” do, in quite different and intriguing ways. If it’s any measure at all, I’ve probably revisited Sound Is more often than any other 2009 release so far. It has its limitations, not least its lack of limitations, but it’s an endlessly fascinating set of music and, if I’m any judge, ushers in a new and freshly creative period for Mazurek.

–Brian Morton

Joe McPhee and The Albert Ayler 2000 Project

Angels, Devils, and Haints

CJR 7

Joe McPhee ushered in the 21st century with a tribute to the musician who inspired him to pick up the tenor saxophone – Albert Ayler. This double CD captures two concerts by the Albert Ayler 2000 Project, an unusual band featuring McPhee and a bass quartet of Michael Bisio, Dominic Duval, Paul Rogers, and Claude Tchamitian. This is essentially group music, with McPhee and the basses creating a dark, intricate sonic mass. Each bassist establishes his own sense of tension and release in relation to the underlying pulse, so the music is simultaneously expanding and contracting at different rates all the time. At times, they deploy themselves to different parts of the instrument’s range, with high arco wails sailing over high and low pizzacato lines, and deep rhythmic patterns. Textures are just as varied – dry rasps, dark molasses bowed tones, percussive rattles. The density changes as bassists drop in and out. The whole sound is constantly in motion, sometimes agitated and urgent, at others more contemplative or serene.

Joe McPhee ushered in the 21st century with a tribute to the musician who inspired him to pick up the tenor saxophone – Albert Ayler. This double CD captures two concerts by the Albert Ayler 2000 Project, an unusual band featuring McPhee and a bass quartet of Michael Bisio, Dominic Duval, Paul Rogers, and Claude Tchamitian. This is essentially group music, with McPhee and the basses creating a dark, intricate sonic mass. Each bassist establishes his own sense of tension and release in relation to the underlying pulse, so the music is simultaneously expanding and contracting at different rates all the time. At times, they deploy themselves to different parts of the instrument’s range, with high arco wails sailing over high and low pizzacato lines, and deep rhythmic patterns. Textures are just as varied – dry rasps, dark molasses bowed tones, percussive rattles. The density changes as bassists drop in and out. The whole sound is constantly in motion, sometimes agitated and urgent, at others more contemplative or serene.

When tempos quicken, McPhee is torrential, pouring out deeply contoured arabesques of sound; when the tempos slow, he rhapsodizes, pensively soaring over the mournful crags of basses. McPhee never plunges into bathos in the way Ayler did, or amplifies emotions into terrifying grotesqueries. He is far more human-scaled, more intimate than Ayler’s cosmos-spanning evocation of godhead. McPhee’s vocabulary of extended techniques, sounds, and textures is always at the service of a basically lyrical conception. This essential melodicism is one thing that gives his music its human dimension. It’s especially evident on “Going Home,” which ends the first disc, and the unaccompanied “Ol’ Man River,” which starts the second disc.

The first concert, from Le Mans, is primarily taken up by a sprawling hour-long improvisation during which the quintet explores its sonic potential. Rather than delve into one area in depth, they test different possibilities, letting curiosity and the music take them where they will. The search is the structure, and the knitting together of sound and feeling the content. There’s a rambling quality to it, with many peak moments to make up for the occasional less fruitful ones. The second concert, recorded 18 days later in Nantes, contains the album’s highlight, a tightly focused 24-minute improvisation, “Angels and Other Aliens.” The shorter length works in its favor, and the group improvises a clear narrative arc. There’s a keen sense of everyone working together and a relaxed rapport among the players that is always the hallmark of a McPhee group.

–Ed Hazell

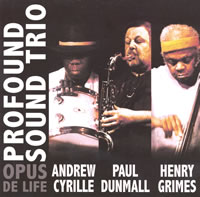

Profound Sound Trio

Opus de Life

FPorter PRCD-4032

Paul Dunmall’s recent success in the US has been understandable cause for celebration back in Blighty, much of the press has overlooked the fact that as a younger man the saxophonist spent some time Stateside, working with Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson, Alice Coltrane and others, this long before he made an impact at home with Spirit Level and Mujician on the jazz/improv front and with an array of folk-tinged projects. Persistence has paid off. For years, Dunmall released a steady stream of work on his own Duns Limited Editions CD-R imprint, documenting a confident appropriation of the saxophone family, clarinets and bagpipes. Now there’s sufficient international awareness of his talents to guarantee steady label interest.

Paul Dunmall’s recent success in the US has been understandable cause for celebration back in Blighty, much of the press has overlooked the fact that as a younger man the saxophonist spent some time Stateside, working with Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson, Alice Coltrane and others, this long before he made an impact at home with Spirit Level and Mujician on the jazz/improv front and with an array of folk-tinged projects. Persistence has paid off. For years, Dunmall released a steady stream of work on his own Duns Limited Editions CD-R imprint, documenting a confident appropriation of the saxophone family, clarinets and bagpipes. Now there’s sufficient international awareness of his talents to guarantee steady label interest.

The ‘post-Coltrane’ label is now as shopworn as the ‘eclectic’ badge, and almost as meaningless, other than in the most unspecific of senses. Dunmall’s characteristic approach is plain-spoken and artisanal, favoring straightforward narration over harmonic complexity, a hard-forged blacksmith’s tone over anything overtly pretty or folkish. Paired with Andrew Cyrille and Henry Grimes, he sounds like a country boy who’s just arrived in town but already shown he’s the equal of anyone on the block, and with his own moves. Opus de Life was taped at the 2008 Vision Festival. It’s a decent enough recording, big and immediate; the crowd’s strongly in evidence, but you can’t quibble with their enthusiasm. The opening ‘This Way, Please’ doesn’t waste any time on preliminaries. Against Grimes’s immense bass sound, plucked and arco, and at an intriguing angle to Cyrille’s peremptory rhythm, Dunmall – on tenor throughout, apart from a digression on the pipes - delivers flurries of urgent, pared sound, like a Border balladeer. Liner note writer Marc Medwin PhD – what’s the doctorate in, Marc? – has him in “an Eastern dream of jasmine-scented melodic exhortations,” when I think you’ll find he’s snuffing pure English blackthorn and elder, which is only ‘Eastern’ from a very Western point of view. There’s nothing much here of Trane’s understanding of raga. It’s closer to Albert Ayler’s parade-ground manner, and Cyrille’s set-up, with rims and blocks already in evidence, is defiantly traditional: Baby Dodds isn’t far away in spirit.

Cyrille takes a grand solo on ‘Whirligigging’ and again on the long ‘Beyonder’, dominant enough to suggest that he’s the guv’nor here. He’s in the driving seat on ‘Call Paul’, where Grimes’s violin mysteriously morphs (less mysteriously if you were present at the Clemente Soto Velez Cultural Center, rather than listening on CD) into Dunmall’s pipes a couple of minutes from the end. Anyone of a Scots or Brythonic background tends to bristle when pipes are used in non-traditional settings, but Dunmall has nailed it and in the process revealed the crudity of Albert’s use of chanter on the late sessions for New Grass, Music Is The Healing Force . . . and The Last Album.

Grimes’s subsequent flurries on fiddle during ‘Beyonder’ and the encore make you wish he’d been carrying it during his time with Ayler, who incorporated strings into Fire Music more effectively than he’s often given credit for; there’s also the unworthy thought that Ornette has been doubling on violin for years without ever sounding this convincing. ‘Beyonder’ runs to a delightful false ending, then the Profound Sound Trio is called back for the scorching ‘Futurity’, which is much larkier (check out Dunmall’s ‘quotes’ and catcalls) than its high-octane delivery might immediately suggest. The guys seemed to have as good a time as the crowd. Let’s hope it’s a regular association.

–Brian Morton

Michael Snow + Alan Licht + Aki Onda

Five A’s, Two C’s, One D, One E, Two H’s Three I’s , One K, Three L’s, One M, Two N’s, Two O’s, One S, One T, One W

VICTO CD 111

This CD consists of two pieces by one of the more unusual improvising ensembles extant. The first piece, the 33-minute “Allorolla” was recorded at FIMAV (Festival international de musique actuelle de Victoriaville) in 2007; the 15-minute “Doo Rain” was recorded in concert in Toronto in 2006. Alan Licht and Aki Onda work regularly as a duo and have previously recorded together. Licht is a versatile and creative guitarist, combining both a strong linear sense and an ability to build densely layered electronic textures; Onda is an extraordinarily original musician, the one whose medium makes the group genuinely mysterious. Using cassette tapes as his fundamental instrument, he transfers them repeatedly until tape and signal degrade into often unpredictable and indecipherable transformations of concrete elements with which he improvises. Michael Snow often joins them and his particular mix of skills both complements and expands this work. Snow will turn 80 this year and it’s likely his international reputation rests primarily on his work as a filmmaker and sculptor. He is, however, a remarkable improviser. Like the late Hal Russell, a musician of the same generation, Snow has improvised over an extraordinary range of contexts. Strongly influenced as a pianist by Jimmy Yancey, he worked regularly in Dixieland in the early ‘50s, and he’s been involved in free improvisation since the 1960s. Like Russell, he’s an intrepid improviser, the free radical in the chemistry set, and here he manages to span the improvising range of his much younger partners, whether it’s developing an orchestral voice at acoustic piano, matching electronic lines and textures with an analogue CAT synthesizer or amplifying a radio to match the verbi-vocal elements among Onda’s taped messages.

This CD consists of two pieces by one of the more unusual improvising ensembles extant. The first piece, the 33-minute “Allorolla” was recorded at FIMAV (Festival international de musique actuelle de Victoriaville) in 2007; the 15-minute “Doo Rain” was recorded in concert in Toronto in 2006. Alan Licht and Aki Onda work regularly as a duo and have previously recorded together. Licht is a versatile and creative guitarist, combining both a strong linear sense and an ability to build densely layered electronic textures; Onda is an extraordinarily original musician, the one whose medium makes the group genuinely mysterious. Using cassette tapes as his fundamental instrument, he transfers them repeatedly until tape and signal degrade into often unpredictable and indecipherable transformations of concrete elements with which he improvises. Michael Snow often joins them and his particular mix of skills both complements and expands this work. Snow will turn 80 this year and it’s likely his international reputation rests primarily on his work as a filmmaker and sculptor. He is, however, a remarkable improviser. Like the late Hal Russell, a musician of the same generation, Snow has improvised over an extraordinary range of contexts. Strongly influenced as a pianist by Jimmy Yancey, he worked regularly in Dixieland in the early ‘50s, and he’s been involved in free improvisation since the 1960s. Like Russell, he’s an intrepid improviser, the free radical in the chemistry set, and here he manages to span the improvising range of his much younger partners, whether it’s developing an orchestral voice at acoustic piano, matching electronic lines and textures with an analogue CAT synthesizer or amplifying a radio to match the verbi-vocal elements among Onda’s taped messages.

“Allorolla” begins acoustically with Snow darting up and down the piano keyboard –hand over hand, bass rumble to random treble splash, with some tremoloed clusters in the middle register before Licht and Onda enter and Snow joins them in constructing a passage through electronic walls. There’s a fondness afoot for the notion that “an improviser is telling a story” and that may be true of some (was that “Little Bo Peep” or Ulysses I heard earlier? or the E flat’s loss of innocence? or does music emphasize their similarity?). Here it may be the epic of Gilgamesh in a flood of electrons, a thick swath of static, hum, pedal-altered guitar chords and taped street scenes and voices—near, distant, in several languages, occasionally singing. The layered sound can create voices of its own, beat patterns and vestigial elements that chime with other components to suggest submerged singers. The shorter “Doo Rain” functions without the acoustics. At times one seems to be listening through the surface sound, washes of noise making spoken messages more urgent, Onda's cassettes a charnel house of memories that somehow arise internally in the listener.

–Stuart Broomer