Moment's Notice

Reviews of Recent Recordings

(continued)

Henry Threadgill Zooid

Tomorrow Sunny/The Revelry, Spp.

Pi Recordings Pi43

Henry Threadgill’s one of those rare musicians capable of making you think differently about music itself. It may be why he isn’t more fulsomely embraced: lots of admiration; plenty of critics prepared to dub him one of the most important of contemporary composers; and didn’t the saintly Studs Terkel include him in And They All Sang? And yet Threadgill doesn’t always get a prominent mention in orthodox narratives of development. That may be because he doesn’t proceed in a smooth, evolutionary way, but seems to make sudden leaps of language, usually expressed by the formation of a new group. Think of the number he’s fronted since Air (and the same air of polite neglect applies to them in spades) and most of us will forget at least one or two of them: the seven-person Sextett, Very Very Circus, X-75, Aggregation Orb, Make a Move and the larger Society Situation Dance Band. On a visit to London around 1990 he told me that changes of personnel were always tied to new compositional dictates rather than any need to rebrand: “I hear a bunch of instruments together and that’s a new sound, not just a new way of doing stuff.” The first recorded outings of Zooid are now a decade ago. Columbia had just about coped with the transition from Very Very Circus to Make a Move, but was plainly baffled by Threadgill’s emulation of Dr Who and didn’t stick with him for long after the subsequent regeneration. Listen a bit harder, though, and there’s perhaps more continuity than even he supposes between one group – or sonic concept – and the next.

Henry Threadgill’s one of those rare musicians capable of making you think differently about music itself. It may be why he isn’t more fulsomely embraced: lots of admiration; plenty of critics prepared to dub him one of the most important of contemporary composers; and didn’t the saintly Studs Terkel include him in And They All Sang? And yet Threadgill doesn’t always get a prominent mention in orthodox narratives of development. That may be because he doesn’t proceed in a smooth, evolutionary way, but seems to make sudden leaps of language, usually expressed by the formation of a new group. Think of the number he’s fronted since Air (and the same air of polite neglect applies to them in spades) and most of us will forget at least one or two of them: the seven-person Sextett, Very Very Circus, X-75, Aggregation Orb, Make a Move and the larger Society Situation Dance Band. On a visit to London around 1990 he told me that changes of personnel were always tied to new compositional dictates rather than any need to rebrand: “I hear a bunch of instruments together and that’s a new sound, not just a new way of doing stuff.” The first recorded outings of Zooid are now a decade ago. Columbia had just about coped with the transition from Very Very Circus to Make a Move, but was plainly baffled by Threadgill’s emulation of Dr Who and didn’t stick with him for long after the subsequent regeneration. Listen a bit harder, though, and there’s perhaps more continuity than even he supposes between one group – or sonic concept – and the next.

Zooid has a settled formation now and a solid-looking arrangement with Pi. The importance of the recording process itself is reflected here in a spoken (female voice) credit which occupies the last two minutes of the record: “I’m trying to take a long view / within reason / about the music / I cannot tell / or say / anything/ about the music / no expectations suggested / … the individual listener / let the music / is all I can offer” is the only programmatic content and it denies any kind of program. Threadgill’s roots, I’d argue, lie back in time with innovations that entered African-American writing and music back in the 1920s, a new vernacular confidence that doesn’t feel uncomfortable with modernity. Threadgill groups always have a faint whiff of the conservatory as well as the juke joint. The presence of cello (Christopher Hoffman these days) as well as trombone or tuba (José Davila), guitar (Liberty Ellman, who also produces), bass guitar and drums (Stomu Takeishi and Elliot Humberto Kavee) offers a group sound that simultaneously sets up quite different expectations. I have a hunch Miles Davis would understand this music and might have taken Michael Henderson down the route Takeishi follows in this group, but Miles didn’t have a composer’s sensibility at bottom. Threadgill does. “Stuff” is about as imprecise as he got in conversation. The stuff of the music is, as ever, detailed synchronization of quite different rhythmic lines. He understands completely that rhythms don’t have to coincide or work in proportions or come out in right phase at the end. Sometimes you put one against another, in the same way as you put a saxophone against a bass guitar and the juxtaposition is the music. That’s what “A Day Off” sounds like, a surreal congeries of musical … stuff that is as beautiful as anything he’s ever delivered and the perfect start to a record that just gets better.

Another reason for Threadgill’s slight marginality is that, on balance, flute is perhaps now his main instrument, not necessarily in terms of time played but certainly based on its importance to his concept. His playing on “Tomorrow Sunny” is titanium-hard, density 21.5 – the passing resemblance to Edgard Varèse in the motivic writing isn’t entirely incidental. There’s bass flute elsewhere, which has a more architectural quality.

“So Pleased, No Clue” starts with an ambiguous rustle, as if the previous act is being moved offstage. Then Threadgill plunges into the bluesiest idea of the set, exquisitely shaped and minimal. “See The Blackbird Now” is where Dolphy might have ended up if he had got back from Berlin, an amazing spacious idea with stunning use of pizz. effects and piezo-bright harmonics. The last two tracks, “Ambient Pressure Thereby” and “Put On Keep / Frontispiece, Spp” seem to track back round to the language of some of the earlier groups, the Sextett most obviously, but there’s so much richness here that one almost needs a pause before taking them on. I’ve been spelling Tomorrow Sunny/The Revelry, Spp with an awed trawl through the Mosaic box of Air, Novus and Columbia recordings. If you’re new to this work, or yet to be convinced, get this one, and then play it back to back with the peerless Rag, Bush and All – one of the most consistently rewarding sequences in the whole of “jazz.”

–Brian Morton

Urumchi

Nar(r)

Leo CD LR 633

This version of the band Urumchi – named for the capital of East Turkestan – is a cross-cultural improvising quartet in which Saadet Türköz, a refugee from East Turkestan who has spent her adult life in Turkey and Switzerland, sings with three Swiss instrumentalists: Hans Hassler on accordion; Alfred Zimmerlin on cello, paper and voice; and Fredy Studer on drums, water, bowed gong and water gong. It’s entirely appropriate that one of the musicians should be credited with playing one of the four elements, because Türköz chants, declaims, and intones songs of absolutely elemental passion. This is apparently not the first version of Urumchi. In 2005 Türköz recorded under the name in Kasakhstan with local musicians playing traditional instruments. In a brief note, she dedicates this CD to the memories of Werner Ludi, as co-founder of Urumchi [no recordings of this version appear to have been released] and to her late brother Ahmet who “was engaged for the independence of East Turkestan and human rights.”

This version of the band Urumchi – named for the capital of East Turkestan – is a cross-cultural improvising quartet in which Saadet Türköz, a refugee from East Turkestan who has spent her adult life in Turkey and Switzerland, sings with three Swiss instrumentalists: Hans Hassler on accordion; Alfred Zimmerlin on cello, paper and voice; and Fredy Studer on drums, water, bowed gong and water gong. It’s entirely appropriate that one of the musicians should be credited with playing one of the four elements, because Türköz chants, declaims, and intones songs of absolutely elemental passion. This is apparently not the first version of Urumchi. In 2005 Türköz recorded under the name in Kasakhstan with local musicians playing traditional instruments. In a brief note, she dedicates this CD to the memories of Werner Ludi, as co-founder of Urumchi [no recordings of this version appear to have been released] and to her late brother Ahmet who “was engaged for the independence of East Turkestan and human rights.”

To some extent Urumchi’s work resembles the way guzheng player Xu-Feng-Xia’s traditional vocals are integrated into performances of improvised music, or the way another Chinese musician, pipa player Yang Jing, integrates traditional compositions with western free improvisation in the Chinese-Swiss quartet Different Song on the recent Step in to the Future (also on Leo). Türköz’s work might be closest to the Tuvan singer Sainkho Namchylak, since the lines between tradition and innovation are very hard to draw here, Türköz drawing on shamanic traditions in work that’s both visceral and hallucinatory, whether she’s improvising lyrics or drawing on traditional melodies.

The pieces here include “Hanci,” a keening song of rare power written by Turkish composer Selahattin Inal; works realized by the group with lyrics by Türköz; songs actually composed by her; and one song with lyrics drawn from Friedrich Nietzsche (the dream-like recitation called “Birds”). In the opening “Avul,” the melody sounds traditional while the orchestration has a kind of infernal repetition. The relative lightness of the instruments is an effective foil to Türköz’s demonic intensity, with Hassler, Zimmerlin and Studer sometimes developing long improvised passages that seem to inspire the singer, as with the intense “Davus” in which she literally chants herself breathless. It may be that the spontaneous music is an ideal foil for these traditions, harkening back to the emotional power that modal roots could often generate in early free jazz. This is music of trans-personal cultural friction in which people match up voice and instruments, contrasting their accumulated inner mathematics – pitches, reverberations – and childhood memories. As such, it’s part of the essential work of contemporary improvised music.

–Stuart Broomer

Various Artists

Echtzeitmusik Berlin

Mikroton CD 14|15|16

In the mid ‘90s, recordings began to come out from Berlin documenting a new sensibility, as groups like King Übü Örchestrü and Sven-Åke Johansson’s trio with Axel Dörner and Andrea Neumann began moving the language of free improvisation away from the brawn and heft that had predominated in the decades before. Then, in short order, came Dörner’s Trumpet on A Bruit Secret and Phosphor’s debut release on Potlatch featuring Dörner, Neumann, Burkhard Beins, Alessandro Bosetti, Robin Hayward, Annette Krebs, Michael Renkel, and Ignaz Schick, bringing notice to what was often referred to as “Berlin Reductionism.” There was a clear resonance with like-minded musicians, particularly in London, Boston, and Tokyo, and a free interchange began, sparked by international travel and an influx of artists who moved to the German capitol.

In the mid ‘90s, recordings began to come out from Berlin documenting a new sensibility, as groups like King Übü Örchestrü and Sven-Åke Johansson’s trio with Axel Dörner and Andrea Neumann began moving the language of free improvisation away from the brawn and heft that had predominated in the decades before. Then, in short order, came Dörner’s Trumpet on A Bruit Secret and Phosphor’s debut release on Potlatch featuring Dörner, Neumann, Burkhard Beins, Alessandro Bosetti, Robin Hayward, Annette Krebs, Michael Renkel, and Ignaz Schick, bringing notice to what was often referred to as “Berlin Reductionism.” There was a clear resonance with like-minded musicians, particularly in London, Boston, and Tokyo, and a free interchange began, sparked by international travel and an influx of artists who moved to the German capitol.

For those keeping tabs on the music via recordings, the burgeoning improv scene seemed far more homogenous than was actually the case. The book Echtzeitmusik Berlin (Wolke), which came out last year, helped put “Berlin Reductionism” within the context of an evolving group of venues and musicians that was more open and stylistically far-reaching. Through a series of essays written by those living in Berlin and frequent visitors, the book documents a community that came together in clubs, house shows, squats, and alternative cultural spaces that sprang up in the city after the fall of the Berlin Wall. The term “Echtzeitmusik,” literally translated as real-time music, began being used in the mid-‘90s, and the Web site echtzeitmusik.de was launched to announce the burgeoning number of concerts throughout the city. Allegiances were formed, cutting across genres, drawing on cracked pop, punk, noise assaults, site-specific sound installations, electronica, free jazz, and improvisation.

As a companion to the book, Mikroton Records, has now released a 3 CD set, compiled by Burkhard Beins and expertly mastered by Nicholas Bussmann, Werner Dafeldecker, and Valerio Tricoli. Over the course of 41 cuts and nearly four hours of music, this set provides an invaluable broad-brush overview of a wildly diverse scene. Taking cues from the scene itself, each CD is an amalgam, eschewing any pigeon-holing of trends or styles, jump-cutting from micro-quiet, timbral explorations to brash assaults, from solos to large ensembles, from sonic abstractions to beat-driven stomps. If any one aesthetic holds all of this together, it is a collective sense of exploration; a willingness to push various forms of sound production and spontaneous music making in new directions by crashing together new and existing forms.

That said, there are trends that emerge. Things kick off with Michael Vorfeld’s “Light Bulb Music No. 2” constructed entirely from the amplified sounds generated by various light bulbs and electrical actuators. Vorfeld transforms his sources into a compositional form of clinks, clatters, and flickering waves of electronic sound. That approach to close-micing and use of real-time manipulation of low-tech electronics pops up repeatedly throughout the set, such as in the piece “Brownout,” a recording of an installation by Serge Baghdassarians and Boris Baltschun utilizing balloons, water drops, and syringes to create a constantly morphing sound field of clicks, buzzes, bursts, and patter. Antje Vowinckel weighs in with “Topping and Tumbling” which is based on the sounds captured from spinning tops. Then there are those like Lucio Capece and Christian Kesten or MEK (Beins, Michael Renkel, and Derke Shirley) who incorporate fans, DC motors, and other mechanical detritus along with acoustic instruments, analog synths, and electronic manipulations into their improvisations.

Pianists are well-represented, though they tend to either heavily prepare their instruments, utilize old-school electric instruments like the DX7, or, in the case of Andrea Neumann, strip away everything but for the strings and soundboard. There’s pianist Magda Mayas’ delicate collaboration with drummer Tony Buck, Jürg Bariletti’s duo with bassist Mike Majkowski, or Hanno Leichtmann and Andrea Neumann’s bustling bursts of looped and processed electronics and amplified and mixed string resonance. Brass and reed instruments are utterly transmuted through the use of modifications and astonishing extended technique, whether trumpet players like Liz Allbee or Axel Dörner (whose duo with Tony Buck is a particular standout), the low end striated groans and growls of Robin Hayward’s microtonal tuba in concert with Morten J. Olsen’s rotating bass drum, or the tectonic shifts of the trio Ttrigger, with Chris Heenan’s contrabass clarinet, Matthias Müllers trombone, and Nils Ostendorf’s trumpet.

This is a scene that is inclusive enough to encompass extensions of the vocabularies of free jazz, thrash noise, and song forms as well. The Paul Lovens, Ignaz Schick, Clayton Thomas trio takes off from the reeds, bass, drums tradition by subverting the post bop language with a skewed sense of time and flow. The Magic I.D. with Margareth Kammerer’s plaintive vocals and guitar, Christof Kurzmann’s electronics and chanted vocals, and the paired clarinets of Kai Fagaschinski and Michael Thieke imbue song forms with a drama and mystery on “Love Is More Thicker” with its processed and looped vocals that weave in and out of the woody quavering clarinets. There’s room for flat-out stomp as well, as proved by the inclusion of MoHa! and their headlong charge with skirling feedback, pounding drums, and cracked electronics.

Each CD also features a large ensemble, providing a view of the cross-fertilization of the various musicians. The first CD showcases the mercurial dronescapes of The Pitch, a group featuring Boris Baltschun on pump organ, Koen Nutters on bass, Morten J. Olsen on vibes, and Michael Thieke on bass clarinet augmented by Johnny Chang on violin, Robin Hayward on tuba, and Chris Heenan on bass clarinet. The septet makes the most of the low-end range of the instrumentation, riding quavering waves of intersecting timbres over the reedy oscillations of pump organ. The inclusion of a piece by Phosphor on the second CD is a natural choice and their contribution, from 2006, was recorded around the same time as their second Potlatch release and fits in with the approach to collective improvisation from that release. This is a group that carved out a distinctive sound through the interaction of destabilized layers of activity as electro-mechanical sound sources skitter across abraded and distressed acoustic instruments. Their improvisation develops in a reverse arc, starting with dense, raw intensity which slowly centers in around spare, carefully placed sounds hung against a collective calm. The 3rd CD ends with a piece by The Splitter Orchestra, a 20 piece all-star ensemble made up of many of the musicians who appear across the set. As with many groups this size, the challenge becomes how to keep things from digressing into a massive blow-out; and it is clear that they all are fully aware of that potential. While working with the massing and sectional interactions, they manage to keep a transparency of sound as the multiple layers of voices weave in and out. It is evident that the group has logged considerable time thinking through their collective approach and the 15 minute piece displays a clear sense of structure and pacing.

This, of course, only scratches the surface of the 3 CDs, and all of the cuts are worth a listen. Through careful choices, well-constructed pacing, stellar production values, and a broadly inclusive reach, this compilation does a great job of providing the listener with a sense of the current musical scene in Berlin. The best that can be said of any compilation is that it leaves you wanting to dig in further; to hear more; to dig out recordings you haven’t listened to in a while and search for recordings by new discoveries. This is one that delivers on all counts.

–Michael Rosenstein

David S. Ware Planetary Unknown

Live at Jazzfest Saalfelden 2011

Aum Fidelity AUM074

I met pianist/multi-instrumentalist Cooper-Moore in 2001 in New York and one of the first opportunities we had to hang out was over pie and tea in a Manhattan diner. Cooper-Moore asked me who some of my favorite saxophonists were. I mentioned Frank Wright and he asked whether I was familiar with David S. Ware. I was, but I answered somewhat foolishly that my preference was for Wright. So it’s somewhat ironic that Ware’s most recent two ensemble recordings include both Cooper-Moore and the late Rev. Wright’s drummer of choice, Muhammad Ali. With regular foil William Parker manning the bass chair, the pie on offer by this ensemble is exceedingly good. The unit has a lot of history – Ware and Parker have played together consistently since the latter half of the 1970s, and the saxophonist’s work with Cooper-Moore goes back even earlier, when they worked together in Boston as part of the cooperative ensemble Apogee (well-represented by the 1979 Hat Hut LP Birth of a Being). But to my knowledge, the four musicians hadn’t worked as a unit before 2010, Muhammad Ali having only recently returned to the scene after years of obscurity.

I met pianist/multi-instrumentalist Cooper-Moore in 2001 in New York and one of the first opportunities we had to hang out was over pie and tea in a Manhattan diner. Cooper-Moore asked me who some of my favorite saxophonists were. I mentioned Frank Wright and he asked whether I was familiar with David S. Ware. I was, but I answered somewhat foolishly that my preference was for Wright. So it’s somewhat ironic that Ware’s most recent two ensemble recordings include both Cooper-Moore and the late Rev. Wright’s drummer of choice, Muhammad Ali. With regular foil William Parker manning the bass chair, the pie on offer by this ensemble is exceedingly good. The unit has a lot of history – Ware and Parker have played together consistently since the latter half of the 1970s, and the saxophonist’s work with Cooper-Moore goes back even earlier, when they worked together in Boston as part of the cooperative ensemble Apogee (well-represented by the 1979 Hat Hut LP Birth of a Being). But to my knowledge, the four musicians hadn’t worked as a unit before 2010, Muhammad Ali having only recently returned to the scene after years of obscurity.

Live at Jazzfestival Saalfelden 2011 captures the Planetary Unknown quartet (taking its name from last year’s barn-burning disc of the same name) performing Ware’s three-movement “Precessional,” which takes some architectural cues from the studio recording (especially the tenor-drum duet in the latter section of part one). The concert contains some of Ware’s most searing and intense “free” playing in recent years, albeit unprovoked by the compact and particulate grooves that worked their way into the “classic quartet” with pianist Matthew Shipp and drummer Guillermo E. Brown. That’s not to say that Planetary Unknown doesn’t move – the quartet swings, but with a robust and chunky energy all its own, buoyed by Ali’s dry, planar thrash and Cooper-Moore’s needling accompaniment and chopped-up barrelhouse. The pianist’s obsessive cellular dissonance on the second movement, which he occasionally builds upon but mostly keeps tightly reigned, is a winking near-affront to Ware’s garish swaths and panning mouthfuls and Ali’s soft breaks. A little goading goes a long way in this instance.

The solo tenor cadenza that opens the performance is reminiscent of Archie Shepp’s furious, blurred opening to “In a Sentimental Mood” from Live in San Francisco (Impulse!, 1966), both soulful and tousled. The ensemble enters in a loose, thick and colorful swirl and, while the music might at first seem to point in a number of different directions at once, the quartet’s internal logic becomes quickly apparent. Ali stacks rhythm in layers against Cooper-Moore’s chordal strikes, and Parker’s pizzicato is a deep and throaty undertow where he invents patterns of complete yet spontaneous symbiosis. Almost imperceptibly the quartet moves into an absolute whorl, high-pitched wails and spiky glossolalia offset by lush, swiping jousts. Ellington, Jaki Byard, and Hasaan Ibn Ali are the pianist’s starting-off points in a glorious, singing solo at fifteen minutes in, hangdog repetition and garish bluesy calls built into resonant pyramid forms that are spread throughout the keyboard. Following a section of introspective plucked rumble, Ware and Ali launch into a taut duet, the tenorman’s split-toned shouts economically supported by dry, rounded brushwork. Bass and piano reenter separately, by which point Ware is absolutely peeling the paint, but one never gets the feeling that any grandstanding is going on, nor is it a free-for-all. Ideas and responses move with extraordinary speed, but they’re organized and born out of respect and congeniality and with that sense of inner stability, it’s hard not to feel a very present swing.

The final section focuses on partnerships, beginning with a gorgeous arco bass and tenor duet that finds Ware’s pulpit-pounding shaded by dusky long tones and harmonic fiddling. Of course, Ware can preach while remaining lyrical – wistful, even – and passages of soaring, high-pitched cries are imbued with pathos. Cooper-Moore is stark and reflective, steely accents somewhat rarefied atop Parker’s wailing-wall. Swells of energy don’t seem to counter the quartet’s reflective state in this closing improvisation, with rhapsodic flickers and wrenching zigzags equally part of the equation. It’s a fine close to a beautiful performance, and though Ware has recently faced significant health challenges, the only fragility on offer here is part of nuanced creativity – all four musicians are elemental in their unwavering commitment to the music.

–Clifford Allen

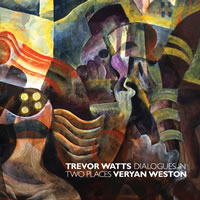

Trevor Watts + Veryan Weston

Dialogues in Two Places

Hi4Head HFCD010D

When Trevor Watts and Veryan Weston released 6 Dialogues on Emanem a decade ago, much was made of the reed player’s “return to free improvisation.” He had participated in the seminal London scene as an integral part of John Stevens’ Spontaneous Music Ensemble; probed at various fusions of rock instrumentation, free jazz and collective improvisation with his group Amalgam; participated in Steve Lacy’s Saxophone Special; and is a member of Barry Guy’s London Jazz Composers Orchestra. But Watts seemed to have shifted his interests in the ‘80s with various incarnations of his Moire Music ensembles which melded pan-cultural rhythms and pulse with free melodicism. Of course, a closer look reveals that the rift was never quite as dramatic or dogmatic as it appeared. While his main focus was certainly on his ensembles, he continued to play in a variety of ad hoc groupings.

When Trevor Watts and Veryan Weston released 6 Dialogues on Emanem a decade ago, much was made of the reed player’s “return to free improvisation.” He had participated in the seminal London scene as an integral part of John Stevens’ Spontaneous Music Ensemble; probed at various fusions of rock instrumentation, free jazz and collective improvisation with his group Amalgam; participated in Steve Lacy’s Saxophone Special; and is a member of Barry Guy’s London Jazz Composers Orchestra. But Watts seemed to have shifted his interests in the ‘80s with various incarnations of his Moire Music ensembles which melded pan-cultural rhythms and pulse with free melodicism. Of course, a closer look reveals that the rift was never quite as dramatic or dogmatic as it appeared. While his main focus was certainly on his ensembles, he continued to play in a variety of ad hoc groupings.

That said, this latest recording with Weston, whom he first met at the Little Theatre Club in London in the ‘70s, is an engaging example of two old friends in intimate dialog. Weston, of course, has proven himself as one of the most attentive duo partners going, working in long-standing partnerships with musicians like Lol Coxhill and Phil Minton, and plying his abstract lyricism with a shrewd ability to freely combine and contrast angular phrasing, jazz voicings, and a refracted romantic lyricism with keen ears toward framing and playing off of his partner. Weston’s resonant clusters and rumbling ostinatos provide an effective foil for Watts’ tart tone and snaking lines, which poke and probe in labyrinthine whorls. The two have worked together on and off ever since their 2001 duo meeting, and the release at hand captures a performance they did at the Guelph Jazz Festival in Ontario, Canada in September, 2011 and another in the intimate setting of the Robinwood Concert House in Toledo, Ohio in June of that year.

The Guelph set frames a 32-minute improvisation with two briefer pieces while the Toledo set is structured around 6 improvisations ranging from 7 to just over 12 minutes long. Regardless of the length, for all the freedom, what comes through is the structural sensibility of both players. The longer form of the Guelph piece moves through a series of extended episodes, reaching some captivating heights, but wanders a bit as the duo moves between sections. They benefit from the shorter forms of the Toledo set, wending their way through arcs of velocity and density. The two also clearly feed off of the intimate setting of the Robinwood Concert House, and the warm, heartfelt response of the audience. Taken together, the two sets provide an effective opportunity to absorb the working strategies of Watts and Weston.

–Michael Rosenstein