Moment's Notice

Reviews of Recent Recordings

(continued)

John Butcher + Mark Sanders

Daylight

Emanem 5024

It may seem bizarre to call so generally understated a recording a scorcher, but that’s in fact precisely how I choose to describe the magnificent Daylight. Filled with a sustained tension and intensity that brings each detail into vibrant relief, it’s got the heat of a most vital organism, star-stuff coming out in sparks. The half-hour “Ropelight” – recorded at 2010’s Freedom of the City festival – sounds in its opening sequences very much like music creating its own context. The piece’s long-held tones sound out parameters and edges, as delicate patterns and rubbed membranes coax more and more grain, evolving into a shared phraseology. It’s breathtaking when improvised music is realized in this fashion, and as marvelous as Butcher is you also must give credit to Sanders’ vast imagination and tonal range. By the time the piece makes its impression, though, there is an almost complete drop into silence that’s an absolute stunner. If you could rock out to a hush, this would be the time. As the piece gathers itself into a new context, Butcher switches to the straight horn, trilling and buzzing inside Sanders’ patient, focused rolls and punctuations.

It may seem bizarre to call so generally understated a recording a scorcher, but that’s in fact precisely how I choose to describe the magnificent Daylight. Filled with a sustained tension and intensity that brings each detail into vibrant relief, it’s got the heat of a most vital organism, star-stuff coming out in sparks. The half-hour “Ropelight” – recorded at 2010’s Freedom of the City festival – sounds in its opening sequences very much like music creating its own context. The piece’s long-held tones sound out parameters and edges, as delicate patterns and rubbed membranes coax more and more grain, evolving into a shared phraseology. It’s breathtaking when improvised music is realized in this fashion, and as marvelous as Butcher is you also must give credit to Sanders’ vast imagination and tonal range. By the time the piece makes its impression, though, there is an almost complete drop into silence that’s an absolute stunner. If you could rock out to a hush, this would be the time. As the piece gathers itself into a new context, Butcher switches to the straight horn, trilling and buzzing inside Sanders’ patient, focused rolls and punctuations.

Of the second and third pieces, from an early 2011 Southampton performance, the bewitching “Flicker” has the simplicity and profundity of a Gerhard Richter painting. Butcher plays into the Sachiko M register in places while Sanders creates controlled whorls of sound. “Glowstick,” by contrast, explores at length the most evident series of contrastive sounds: a high springy tone set against rustle or a coil of overtones against lone thwack. The record is riveting, alive and mercurial. Here a declamatory change of course, there a sizzling burr of a sax tone, and always more movement, each time as if the musicians are peering inside the music in real time. They’re not exactly inventing a world that will be wholly unfamiliar to listeners here but they do realize and guide us through it in the most marvelous ways.

–Jason Bivins

John Cage

Music of Changes

hat [now] ART 173

Sonatas & Interludes

hat [now]ART 152

Surprisingly, the first months of the John Cage centenary have produced few celebratory recordings. This pair of CDs of Cage’s early solo piano music may prove to be among the most significant releases of the anniversary – and one of them is a reissue. Sonatas & Interludes (1946-8) and Music of Changes (1951) are arguably Cage’s most important solo piano pieces where actual keying occurs; James Tenney’s late-life interpretation of the former, Cage’s largest canvas for prepared piano, and David Tudor’s 1956 WDR reading of the latter, which introduced chance operations into Cage’s compositional process, have considerable historical weight.

Surprisingly, the first months of the John Cage centenary have produced few celebratory recordings. This pair of CDs of Cage’s early solo piano music may prove to be among the most significant releases of the anniversary – and one of them is a reissue. Sonatas & Interludes (1946-8) and Music of Changes (1951) are arguably Cage’s most important solo piano pieces where actual keying occurs; James Tenney’s late-life interpretation of the former, Cage’s largest canvas for prepared piano, and David Tudor’s 1956 WDR reading of the latter, which introduced chance operations into Cage’s compositional process, have considerable historical weight.

Sonatas & Interludes is an example of an approach to music-making that was outgrowing its original impetus and context, and becoming something new in the process. Most of Cage’s early works for prepared piano were scores for dances, which is why compositions like “Bacchanale” and “The Perilous Night” are far more programmatic than his subsequent music. The priority for pulse in these works also helped Cage circumvent what his teacher Arnold Schönberg thought was his weak grasp of harmony. Cage’s treatments are clearly in the service of supporting different voices in the scores, which produces a semblance of ensemble music. In the sixteen sonatas and four interludes, the well-roundedness and the atmospherics of Cage’s earlier prepared piano solos are heard in a new context – one without dancers and choreographers. Cage uses sonata form primarily as a unit of measure, a whole to be divided and filled with material. There’s a pointed lack of sophistication in Cage’s themes and developments; yet the compact form and short durations of the pieces are conducive to an attractive, taut lyricism, albeit one that Cage would soon abandon. Tenney’s performance reflects the pivotal role Sonatas & Interludes played in the younger composer’s development – as a teenager, Tenney attended a 1951 concert where Cage performed the work. Tenney’s reading is absorbing; he is intimate enough with the score to understand how Cage was then becoming dispassionate about composition; expression was taking a back seat to design and process, and the idea was taking root that the most interesting music Cage could make was outside his control. Tenney captures the moment of becoming that is the essence of Cage’s Sonatas & Interludes.

By the time Tenney first heard Sonatas & Interludes, Cage had already found the means to bypass taste and memory, the obstacles he wanted to overcome – the I Ching. Without the dice-rolling, Cage may have well composed Music of Charts; it separated him from Boulez and Stockhausen, who also drafted meticulous charts that determined every aspect of the material down to the nth degree. Tudor was the obvious, if not the only choice to champion this work; his comment that while performing Music of Changes he was “watching time rather than experiencing it” reveals the new relationships Cage envisioned for composers, performers and listeners alike as they participated in something new, but at an emotional distance. Cage’s methods promote this distancing, as they result in thorough discontinuity. The piece is littered with moments that could easily be heard as freely improvised; yet, free improvisations tend to have a discernible development that is absent here. Still, there’s a strange magnetic property to the music that not only keeps the listener engaged, but riveted. Virgil Thomson once remarked that the new lyricism exemplified by Sonatas & Interludes was that of “a ping, qualified by a thud;” in Music of Changes, the ping and the thud are autonomous events without any design on Cage’s part that they are related to each other. The very moment when the listener quits straining to discern relationships among the materials and an overarching design is precisely when the music can be fully heard. Tudor figured that out, which is why this performance still resonates more than a half-century after it was recorded.

–Bill Shoemaker

Gerd Dudek

Day and Night

Psi 12.05

German tenor saxman Gerd Dudek is an eclectic, mainly a follower of John Coltrane. What’s unusual is that his inspiration is Coltrane’s early Atlantics, the Giant Steps period of exultant rhythmic and formal freedom. He plays a minimum of scales and double-time. While Dudek offers lots of Coltraneish phrasing, his accents are dispersed, he swings freely over the rhythms instead of hitting downbeats Coltrane-style. In fact, his solo on the one Coltrane tune on this CD, “Blues to You,” is mainstream hard bop, a fruitful five-minute stroll that doesn’t sound at all like Coltrane. The two best improvisations are on the two best songs. Dudek captures some of Ornette Coleman’s thematic-improvisation spirit in the way he spins broken lines from “Congeniality” motives. Herbie Nichols’ Step Tempest” is even more provocative, lyrical playing in a harmonic terrain at a tangent to the original changes.

German tenor saxman Gerd Dudek is an eclectic, mainly a follower of John Coltrane. What’s unusual is that his inspiration is Coltrane’s early Atlantics, the Giant Steps period of exultant rhythmic and formal freedom. He plays a minimum of scales and double-time. While Dudek offers lots of Coltraneish phrasing, his accents are dispersed, he swings freely over the rhythms instead of hitting downbeats Coltrane-style. In fact, his solo on the one Coltrane tune on this CD, “Blues to You,” is mainstream hard bop, a fruitful five-minute stroll that doesn’t sound at all like Coltrane. The two best improvisations are on the two best songs. Dudek captures some of Ornette Coleman’s thematic-improvisation spirit in the way he spins broken lines from “Congeniality” motives. Herbie Nichols’ Step Tempest” is even more provocative, lyrical playing in a harmonic terrain at a tangent to the original changes.

Pianist Hans Koller, another eclectic, has made a hard, aggressive art out of ideas from the best post-Powell, post-Monk, pre-Cecil Taylor ancestors. No prettiness here, but lots of rugged melody. Dudek and Koller are good, honest craftsmen who apparently thrive on equally forceful accompaniments. But bassist Oli Hayhurst sometimes plays a straight ahead swing and, at other times, is MIA, either laying out or plucking shy contrary tones. And drummer Gene Calderazzo sounds simply reckless and compulsively busy to me – he sounds preoccupied; he doesn’t seem to be listening to Dudek and Koller.

By the way, “Day and Night” appears a decade after Dudek’s other Psi CD, ‘smatter, which includes a wild, crazy version of “Body and Soul.” He’s had a long career as a sideman. Are these two the only albums that he’s led?

–John Litweiler

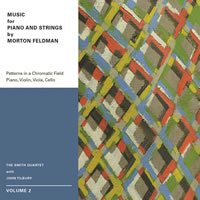

Morton Feldman

Music for Piano and Strings by Morton Feldman, Volume 2

Matchless DVD

One can hardly think of a musician more in tune with Morton Feldman’s expansive approach to compositional structure than John Tilbury. His seminal work with Cornelius Cardew first exposed the pianist to the music of Feldman in the late ‘50s and he was amongst the first to perform Feldman’s work in Europe. Then, of course, there is Tibury’s long association with AMM, where he joined with like-minded improvisers to create and refine radically unique approaches to collective invention. Tilbury has cemented himself as one of the preeminent performers of the piano music of Feldman, having performed his music extensively since 1960 and, along the way, slowly amassed an impressive, and thoroughly thought out collection of recordings of Feldman’s music. There is the monumental 4 CD collection of the solo piano music on the London Hall label (regrettably out of print but well worth searching out) as well as a definitive recording of “Triadic Memories” on the Atopos label.

One can hardly think of a musician more in tune with Morton Feldman’s expansive approach to compositional structure than John Tilbury. His seminal work with Cornelius Cardew first exposed the pianist to the music of Feldman in the late ‘50s and he was amongst the first to perform Feldman’s work in Europe. Then, of course, there is Tibury’s long association with AMM, where he joined with like-minded improvisers to create and refine radically unique approaches to collective invention. Tilbury has cemented himself as one of the preeminent performers of the piano music of Feldman, having performed his music extensively since 1960 and, along the way, slowly amassed an impressive, and thoroughly thought out collection of recordings of Feldman’s music. There is the monumental 4 CD collection of the solo piano music on the London Hall label (regrettably out of print but well worth searching out) as well as a definitive recording of “Triadic Memories” on the Atopos label.

A series of releases on Matchless documenting the performances of Feldman’s music for piano and strings performed by Tilbury and The Smith Quartet at the 2006 Huddersfield Festival of Contemporary Music can now be added to that list. The first volume, which came out a few years back, offered up a mesmerizing performance of “For John Cage,” a duo for piano and violin along with “Piano and String Quartet,” a hyper-focused dive into the resonances of the five instruments. This, the second of a planned three volumes, features performances of two more pieces from Feldman’s later work. A third volume will collect pieces from ‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s. All three are on DVD, requiring playback on a computer, but allowing a full immersion in 90+ minute compositions without requiring the shuffle of CDs or flipping of records.

First up is “Patterns in a Chromatic Field,” a piece for piano and cello from 1981. Over the course of nearly 90 minutes, Feldman’s score places motivic kernels voiced by the two instruments across a long arc with an organic sense of movement. Rather than the slowly unfolding striated lines of much of Feldman’s later work, “Patterns…,” as its name would imply, utilizes phrases voiced by the two instruments which are refracted, inverted, and stretched out with hypnotically subtle micro-variations. What distinguishes Tilbury and cellist Deirdre Cooper’s playing is their unwavering attention to attack and sustain, willing the notes into existence and then raptly measuring their presence within the context of the unfolding flow of the piece. There are sections where they place sharply articulated clusters into the sound space with crystalline angularity and others where tones seem to emerge from the sonic ground. But in both cases, the music is shaped by the directed decisions on the part of the performers in the measurement of dynamics and touch, from the quietest wafts of sound to sharp explosiveness moving along parallel paths and then converging with almost contrapuntal interwoven insistency. This is demanding listening, tracing the memories of patterns as they emerge and evolve throughout the piece. But Tilbury and Cooper’s keen sense of phrasing, duration, and the evolution of the underlying cells never flag for a moment, providing a steadfast thread for the entire duration.

“Piano, Violin, Viola, Cello” from 1987 was the last piece that Feldman composed and it is infused with the slowly moving, methodical pacing that the composer utilized in his final years. As with “Patterns…,” Tilbury and his companions – violinist Darragh Morgan, violist Nic Pendlebury, and cellist Cooper – fully immerse themselves in the structure of the music. The score is constructed around a more measured phrasing and protracted flow, maximizing the timbral depth of resonant, bell-like chimes of piano and the dark sonorities of the massed strings. Here in particular, Tilbury’s astonishing control of touch is in full display as attack is minimized, letting the notes appear fully formed and then gradually dissolve. The string players respond in kind, with richly nuanced bowing, shaped by meticulous attentiveness to the sonic space. There is a processional stateliness as the four judiciously place their hanging dissonances, letting the harmonics ring against each other and then decay with breath-like pacing. And that feel for pacing is particularly critical in this piece, as the tempo and dynamic range hardly varies across the 90 minutes, focusing one’s listening instead on the subtle modulations of pulse and tonalities. The four musicians are savvy enough to develop an elusive drama as the various layers drift across the collective undercurrent.

–Michael Rosenstein

Fly

Year Of The Snake

ECM 2235 2776644

Since their self-titled 2004 debut for Savoy, the cooperative ensemble Fly has subtly circumvented the traditional dynamics of the classic saxophone, bass and drums trio standardized by innovators like Sonny Rollins, Joe Henderson and others. Bolstered by nearly a decade performing together, tenor saxophonist Mark Turner, bassist Larry Grenadier and drummer Jeff Ballard continue to evince a democratic ideal on Year Of The Snake, their third album (and second for ECM, following 2009’s Sky & Country). The trio’s conversational rapport imbues the record’s seven original compositions and five improvised vignettes with a refined sense of freedom, subverting customary expectations regarding the roles of soloist and accompanist in the process.

Since their self-titled 2004 debut for Savoy, the cooperative ensemble Fly has subtly circumvented the traditional dynamics of the classic saxophone, bass and drums trio standardized by innovators like Sonny Rollins, Joe Henderson and others. Bolstered by nearly a decade performing together, tenor saxophonist Mark Turner, bassist Larry Grenadier and drummer Jeff Ballard continue to evince a democratic ideal on Year Of The Snake, their third album (and second for ECM, following 2009’s Sky & Country). The trio’s conversational rapport imbues the record’s seven original compositions and five improvised vignettes with a refined sense of freedom, subverting customary expectations regarding the roles of soloist and accompanist in the process.

Ebbing and flowing between impressionistic abstraction and unadorned lyricism, their sophisticated interplay embellishes oblique frameworks with elaborate rhythms and vivid textures, infusing the bustling groove of the Afro Latin-tinged “Festival Tune” and quicksilver tempo of the angular title track with simmering intensity. Turner’s sinuous altissimo phrases, Grenadier’s melodious filigrees and Ballard’s sprightly percolations weave a multihued mosaic, whether navigating the soulful funk of “Benj” or the bluesy changes of “Salt And Pepper.” On “Kingston,” Grenadier’s sinewy arco offers stirring, neo-classical counterpoint to Turner’s elliptical cadences and Ballard’s prismatic accents – a calibrated effort that gracefully ascends to a kaleidoscopic climax.

The date’s stately air is reinforced by episodes of serene reflection; Turner, Grenadier and Ballard sound especially inspired in quieter moments, whether austere (“Brothersister”) or optimistic (“Diorite”). Their affinity for employing space and silence is expertly realized on the five impromptu variations of “The Western Lands” interspersed throughout the program, brief interludes where Ballard’s skittering ruminations contrast with Turner’s hushed musings and Grenadier’s atmospheric interjections. Elegant and urbane, Year Of The Snake confirms Fly as the perfect vehicle for Turner, Grenadier and Ballard to demonstrate their mastery of nuance and restraint.

–Troy Collins