Moment's Notice

Reviews of Recent Recordings

(continued)

Susan Alcorn & George Burt

A & B

Iorram Records AH79

This is a guitar duet with a difference, pairing Glasgow-based electric guitarist George Burt with American pedal-steel player Susan Alcorn in a program of duets recorded during the GIO (Glasgow Improvisers Orchestra) Festival in October, 2009. The pedal-steel is an instrument little-used in improvised music, though it’s an obvious ancestor to the table-top approach of Keith Rowe, et al. If the instrument has a drawback, it’s the obviousness of its capacity for pitch fluctuation, from its slide to its tuning pedals. It’s entirely to Alcorn’s credit that she’s mastered not only the instrument but any impulse to deploy its pitch-bending resource with anything but taste and creativity, from sounding like a piano interior on “Sonic booms and euphuism” to the glassy glissandos of “Retro-rockets and peripeteia.” Only the very brief and brilliant “DNB and TNT” gives the pedal-steel free rein. Instead the music is usually alive with the subtlest pitch-bends, at times so incremental that Alcorn and Burt’s guitars can pass in and out of identity. There’s a tendency to alternate jazz-like improvisations that emphasize linear development and lyrical sounds with more sonic approaches that explore a certain sci-fi potential inherent in the electronics and the wavering pitches, sometimes developing a quality as ethereal as Harry Partch’s music. Alcorn seems ideally matched with Burt whose approach to the guitar is as musically focused and tonally acute as her own, bends and singing tones constantly complementing one another. A & B is released by the Glasgow micro label Iorram in an edition of 100 CD-Rs. This is fascinating work that deserves to reach a larger audience.

This is a guitar duet with a difference, pairing Glasgow-based electric guitarist George Burt with American pedal-steel player Susan Alcorn in a program of duets recorded during the GIO (Glasgow Improvisers Orchestra) Festival in October, 2009. The pedal-steel is an instrument little-used in improvised music, though it’s an obvious ancestor to the table-top approach of Keith Rowe, et al. If the instrument has a drawback, it’s the obviousness of its capacity for pitch fluctuation, from its slide to its tuning pedals. It’s entirely to Alcorn’s credit that she’s mastered not only the instrument but any impulse to deploy its pitch-bending resource with anything but taste and creativity, from sounding like a piano interior on “Sonic booms and euphuism” to the glassy glissandos of “Retro-rockets and peripeteia.” Only the very brief and brilliant “DNB and TNT” gives the pedal-steel free rein. Instead the music is usually alive with the subtlest pitch-bends, at times so incremental that Alcorn and Burt’s guitars can pass in and out of identity. There’s a tendency to alternate jazz-like improvisations that emphasize linear development and lyrical sounds with more sonic approaches that explore a certain sci-fi potential inherent in the electronics and the wavering pitches, sometimes developing a quality as ethereal as Harry Partch’s music. Alcorn seems ideally matched with Burt whose approach to the guitar is as musically focused and tonally acute as her own, bends and singing tones constantly complementing one another. A & B is released by the Glasgow micro label Iorram in an edition of 100 CD-Rs. This is fascinating work that deserves to reach a larger audience.

–Stuart Broomer

Julian Argüelles

Ground Rush

Clean Feed CF191

There’s an apparent nod to Coltrane in the title of the opening “Mr MC”, but tenor saxophonist Julian Argüelles’ language is all Rollins, a nicely articulated bop line that is quickly doubled by the bass in a quick, intimate exchange or out front in a more abstract version of itself. After the propulsive opening, Argüelles tugs back on the beat, spinning out a set of nice variations on the line that seems to revolve round a single, ladder-like run down the scale. There’s another tenor saxophone homage right at the end, or at least one assumes that “Redman” is a nod to Dewey and at every sort of level this makes sense, because the other obvious source for these tersely melodic, harmonically sprung pieces is the Ornette Coleman Trio with David Izenzon and Charles Moffett.

There’s an apparent nod to Coltrane in the title of the opening “Mr MC”, but tenor saxophonist Julian Argüelles’ language is all Rollins, a nicely articulated bop line that is quickly doubled by the bass in a quick, intimate exchange or out front in a more abstract version of itself. After the propulsive opening, Argüelles tugs back on the beat, spinning out a set of nice variations on the line that seems to revolve round a single, ladder-like run down the scale. There’s another tenor saxophone homage right at the end, or at least one assumes that “Redman” is a nod to Dewey and at every sort of level this makes sense, because the other obvious source for these tersely melodic, harmonically sprung pieces is the Ornette Coleman Trio with David Izenzon and Charles Moffett.

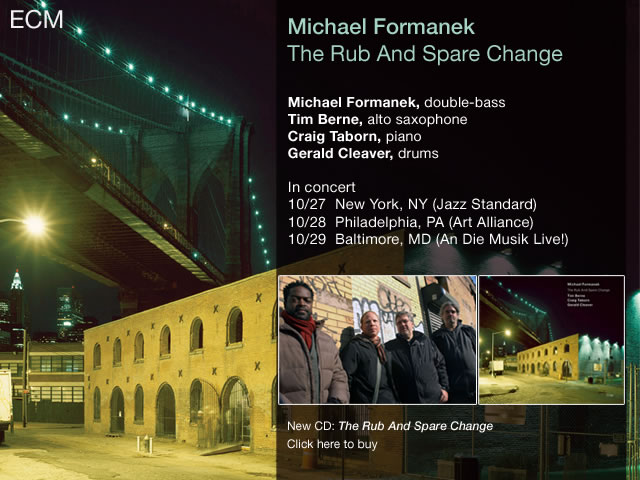

Michael Formanek even manages to find something of Izenzon’s rich cantorial authority on the opening track and it is he who winds up the long ostinato mid-section that, in turn, highlights Tom Rainey’s drumming. The unexpected dance feel gives way to the quiet ‘Fife’, a sea-fogged – they call it ‘haar’ there – meditation that links a number of isolated ideas into one satisfying sequence, held together by Formanek’s bass.

Like “Know Excuses” later, and at precisely the same duration, “Filthy Rich” is a group improvisation or collective composition. It’s difficult to judge which is more likely. One thing one has learned about Argüelles is that he is capable of finding melody in almost any setting and context, whether in a big band or playing with minimum accompaniment. He doesn’t even seem to rely on Formanek for a root chord and operates confidently without obvious support.

“Blood Eagle” anticipates the Redman connection with a staccato statement and tight percussion packed in behind the saxophone. Anyone not familiar with Dewey’s Coincide with Sirone and Eddie Moore might not consider the link convincing, albeit in a gentler mode on Argüelles’s record. “From One JC To Another” is another thoughtful idea, with the saxophonist – who plays tenor throughout; no baritone this time – working up in the higher register for significant parts of the way. It’s obvious what “Bulerias” draws from flamenco, an Iberian tinge and some limber, balls-of-the-feet playing, but the form is quickly enough dispensed with. It reveals another aspect of Argüelles’s complex musical inheritance, though, and it’s never been more confidently integrated with his other interests.

This is a second outing for the trio, following Partita on the Basho label. It unmistakably represents a step forward, not just in the integration of voices but also in Argüelles’s ability to deliver thoughtful, open-ended themes that are just as satisfying as “songs” as they are as bases for improvisations. There’s good reason to wonder whether close personal contact with the Rae family – Cathie is his partner – has opened him up to musical sources he might previously have overlooked. One hesitates to call them “folkish”, but there is something of that simple but subtly inflected narration to the writing and playing. With this, Argüelles stakes a claim to the front rank in British and European jazz, except he’s already a confidently cosmopolitan figure.

–Brian Morton

Ab Baars

time to do my lions

Wig 17

time to do my lions is Ab Baars’ first solo album in over a dozen years; intriguingly, the new set revisits “Gammer,” which the multi-instrumentalist included on Verderame (Geestgronden; 1997). A clarinet piece that mixes a few brays with puckish, almost Stravinsky-like phrases, “Gammer” – which translates as “donkey-like” – pays homage to Misha Mengelberg’s unique mix of whimsy and obstinacy. It’s not that the material has been radically overhauled; instead, the main difference between the two is the expected deepening of sound that comes with time. However, this should not be taken as a suggestion that Baars has somehow mellowed over the years: everything from “Nisshin joma,” a piece for shakuhachi that quavers in a gentle, yet foreboding manner, and “The rhythm is in the sound,” a blisteringly intense tenor piece, indicates that Baars has become a noticeably more rigorous player since then, a notion that would have seemed improbable at the time. In the ‘90s.his rigor registered more as formalism, which certainly remains in the foreground here through his sequencing of the album’s ten starkly contrasting tracks, as well as the exposition of materials – the opening tenor piece, “Day and Dream,” exemplifies how Baars painstakingly sifts the gold out of a string of motives. The difference lies in the ongoing refinement of Baars’ temperament; he’s always had an implacable coolness even when he’s screeching and screaming, but it has morphed. It’s now something akin to what Baars writes in his note for “Purple petal” about the late composer and saxophonist Paul Termos – “a master in making something beautiful out of seemingly barren material.” Like Termos’, Baars’ music may often seem austere or remote; but it’s essentially deadpan, downplaying its own pathos and humor. “Purple petal” is the case in point. There’s an initially inchoate feel to how Baars scrawls the piece’s hymn-like contours, but soon his clarinet is careening cannily, its widening vibrato suggesting a wind-up to a dramatic climax before the piece abruptly stops without harmonic resolution. The piece has something of a koan-like inscrutability, but it nevertheless strikes a strong emotional chord. To one degree or another, Baars does something similar on every piece on time to do my lions.

time to do my lions is Ab Baars’ first solo album in over a dozen years; intriguingly, the new set revisits “Gammer,” which the multi-instrumentalist included on Verderame (Geestgronden; 1997). A clarinet piece that mixes a few brays with puckish, almost Stravinsky-like phrases, “Gammer” – which translates as “donkey-like” – pays homage to Misha Mengelberg’s unique mix of whimsy and obstinacy. It’s not that the material has been radically overhauled; instead, the main difference between the two is the expected deepening of sound that comes with time. However, this should not be taken as a suggestion that Baars has somehow mellowed over the years: everything from “Nisshin joma,” a piece for shakuhachi that quavers in a gentle, yet foreboding manner, and “The rhythm is in the sound,” a blisteringly intense tenor piece, indicates that Baars has become a noticeably more rigorous player since then, a notion that would have seemed improbable at the time. In the ‘90s.his rigor registered more as formalism, which certainly remains in the foreground here through his sequencing of the album’s ten starkly contrasting tracks, as well as the exposition of materials – the opening tenor piece, “Day and Dream,” exemplifies how Baars painstakingly sifts the gold out of a string of motives. The difference lies in the ongoing refinement of Baars’ temperament; he’s always had an implacable coolness even when he’s screeching and screaming, but it has morphed. It’s now something akin to what Baars writes in his note for “Purple petal” about the late composer and saxophonist Paul Termos – “a master in making something beautiful out of seemingly barren material.” Like Termos’, Baars’ music may often seem austere or remote; but it’s essentially deadpan, downplaying its own pathos and humor. “Purple petal” is the case in point. There’s an initially inchoate feel to how Baars scrawls the piece’s hymn-like contours, but soon his clarinet is careening cannily, its widening vibrato suggesting a wind-up to a dramatic climax before the piece abruptly stops without harmonic resolution. The piece has something of a koan-like inscrutability, but it nevertheless strikes a strong emotional chord. To one degree or another, Baars does something similar on every piece on time to do my lions.

–Bill Shoemaker

Ran Blake

That Certain Feeling (George Gershwin Songbook)

hatOLOGY 699

Ran Blake + Sara Serpa

Camera Obscura

Inner Circle Music INCM 015CD

The thread between the titles of Ran Blake’s 1990 immersion into George Gershwin’s songs and his 2009 constitutional with singer Sara Serpa says a lot about the Third Streaming pianist’s sensibility. “Certain” is particularly nuanced, inferring both specificity and security, whereas the thousand year-old optical instrument signifies hermetic knowledge. Blake is often perceived as one of jazz’s more cloistered innovators, tucked away in the recesses of New England Conservatory, honing his unique and fragile insights into the cross-pollination of musical traditions. At the same time, there is an emotional directness to his music, even at its most abstract, that swathes the listener in film noir, Monk, and the rest in an oddly comforting way. Sure, there are jarring dissonances and silences in Blake’s music; there are themes that are left hanging on a cliff; and there are foreboding undercurrents and lurking menaces lacing through his albums. Yet, the specificity of Blake’s choices and the security with which he makes them lights the way for the listener.

The thread between the titles of Ran Blake’s 1990 immersion into George Gershwin’s songs and his 2009 constitutional with singer Sara Serpa says a lot about the Third Streaming pianist’s sensibility. “Certain” is particularly nuanced, inferring both specificity and security, whereas the thousand year-old optical instrument signifies hermetic knowledge. Blake is often perceived as one of jazz’s more cloistered innovators, tucked away in the recesses of New England Conservatory, honing his unique and fragile insights into the cross-pollination of musical traditions. At the same time, there is an emotional directness to his music, even at its most abstract, that swathes the listener in film noir, Monk, and the rest in an oddly comforting way. Sure, there are jarring dissonances and silences in Blake’s music; there are themes that are left hanging on a cliff; and there are foreboding undercurrents and lurking menaces lacing through his albums. Yet, the specificity of Blake’s choices and the security with which he makes them lights the way for the listener.

Blake does this on both That Certain Feeling and Camera Obscura. While the latter is more representative of the breadth of materials Blake regularly investigates, and Serpa’s voice has a wispy, cool innocence well-suited for the subtleties of chestnuts like “Driftwood” and the playfulness of “Nutty,” the Gershwin collection, a mix of solos and duets and trios with Ricky Ford and Steve Lacy, is the more profound statement. Even though Gershwin is bedrock American song, his canon is not central to Blake’s aesthetic. For an artist who regularly returns to wellspring pieces, it’s noteworthy that he’s only recorded one Gershwin song more than once – “My Man’s Gone Now,” first waxed for the ’94 tribute to Sarah Vaughn, Unmarked Van (Soul Note) and Sonic Temples (GM), a 2000 trio date. Gershwin has not been a priority for Ford and Lacy, either; the most concentrated period of Lacy playing Gershwin is his ‘50s sideman dates with Whitey Mitchell and Dick Sutton.

Subsequently, there’s no trace of default-setting interpretations of “The Man I Love,” “I Got Rhythm” and the other songs included in Blake’s program that have been embedded into jazz’s collective consciousness (“Program” should be taken literally with Blake, who is known to pass around print-outs of an evening’s fare at club gigs). This is not to say that Blake has obscured the songs with his prism-like arrangements; if anything, the melodies are intensified by the sparseness of his piano, Lacy’s ability to let a phrase drift almost too long before snapping it back into line, and Ford’s array of sighs, moans and muffled roars. There are some stunning performances scattered throughout the album. Lacy’s reading of “The Man I Love” with Blake is spellbinding, as Lacy alternately milks the romance of the piece and tugs at the changes with against-the-grain phrasing. Ford and Lacy are equally magnetic on their duo take on “Someone To Watch Over Me;” they swirl about each other in the eddies of the theme, slipping back into the main current of the melody where their lines lap over each other, sometimes approximating fugue in their ability to create a statement with small fragments. The trio doesn’t exactly romp on “Strike Up The Band;” but there is a palpable camaraderie among the three that is absolutely winning. Of course, all of these moments are laced together by Blake’s well-faceted solos, each of which are self-contained treatises on Gershwin, the symbiosis of silence and sound in music, and the delicate, real-time art of Streaming.

Serpa is given a severe test of her abilities by singing what is arguably Blake’s signature composition, “Vanguard,” replete with the lyrics the great Jeanne Lee found in a Dostoevsky text in the early ‘60s. She passes, but not with flying colors; she doesn’t have impressive strength reaching and sustaining her highest notes, and she does not have Lee’s rich darker tones at the bottom of her range. Still, give her props for her handling of the text and some nuanced phrasing. There are several other songs on the album that are better suited to her voice – “When Sunny Gets Blue,” “Get Out Of Town,” and “April In Paris” underline her alluring mix of insouciance and vulnerability. Blake is very attentive to these attributes throughout the album, and the choices he makes are unerringly spot-on and frequently poignant, just as his choices are when he’s on his own. Serpa may well establish herself in the top tiers of singers in the next few years; if she does, her stature will be traced back to the promise these performances exude.

–Bill Shoemaker

The Cookers

Warriors

Jazz Legacy Productions JLP 1001009

Instigated by trumpeter David Weiss, one of the more determined flame-keepers of recent years, The Cookers reunites several musicians whose decades-long associations affirm the progressive spirit of early ‘70s straight-ahead jazz, one which is always needed now more than ever. There are very few musicians that embody this notion as persuasively as tenor saxophonist Billy Harper, and it’s telling that most of the septet worked with him at critical junctures: Pianist George Cables played on Harper’s classic ’73 Strata East album, Capra Black. Billy Hart was the drummer of another stellar ensemble that debuted on Strata East – Great Friends, the collective rounded out by Stanley Cowell, Sonny Fortune and Reggie Workman. Trumpeter Eddie Henderson, who first played with Harper in the Jazz Messengers’ front line, joined Harper on his under-heralded Somalia (Evidence), the palpable ’93 plea to end famine and violence in the failed East African state. Hart and Henderson blazed one of the more significant trails in fusion with Herbie Hancock’s Mwandishi sextet; the drummer also performed on bassist Cecil McBee’s ’74 debut as a leader – Mutima, also on Strata-East.

Instigated by trumpeter David Weiss, one of the more determined flame-keepers of recent years, The Cookers reunites several musicians whose decades-long associations affirm the progressive spirit of early ‘70s straight-ahead jazz, one which is always needed now more than ever. There are very few musicians that embody this notion as persuasively as tenor saxophonist Billy Harper, and it’s telling that most of the septet worked with him at critical junctures: Pianist George Cables played on Harper’s classic ’73 Strata East album, Capra Black. Billy Hart was the drummer of another stellar ensemble that debuted on Strata East – Great Friends, the collective rounded out by Stanley Cowell, Sonny Fortune and Reggie Workman. Trumpeter Eddie Henderson, who first played with Harper in the Jazz Messengers’ front line, joined Harper on his under-heralded Somalia (Evidence), the palpable ’93 plea to end famine and violence in the failed East African state. Hart and Henderson blazed one of the more significant trails in fusion with Herbie Hancock’s Mwandishi sextet; the drummer also performed on bassist Cecil McBee’s ’74 debut as a leader – Mutima, also on Strata-East.

However, the sum of the music far exceeds the total of discographical connections between the five veterans; to this end, the presence of Weiss and Craig Handy, heard on both alto saxophone and flute, cannot be overstated. They beef up the ensembles to fully realize the distinguishing details of Cables, Harper and McBee’s compositions (it’s disappointing that none of Hart’s are included); the vigor and fluency of their solos compare well with the veterans’. Respectively, Weiss and Handy have the unenviable task of following a classic exclamatory Harper solo on “Priestess,” one of his signature anthems; another is “Capra Black,” on which Weiss again follows Harper in the solo order. Both the trumpeter and the altoist understand the key to Harper’s pieces is the specificity of his phraseology, which draws upon everything from gospel to traditional Japanese music, as much as their thunderous locomotion. Weiss also deftly arranges Cables and McBee’s compositions; Handy’s flute capers nimbly on the pianist’s lissome “Spookarella” while his alto projects vulnerable warmth on the bassist’s ballad, “Close to You Alone.” Subsequently, the veterans’ consistently sterling work is presented within a context that is organic, the polar opposite of most all-star band schemes.

Had they not already settled on “The Cookers,” a perfectly tailored name for the septet would have been the title of the fiery Freddie Hubbard tune they nail to lead off the album – “The Core.”

–Bill Shoemaker