Moment's Notice

Reviews of Recent Recordings

(continued)

Anouar Brahem

The Astounding Eyes of Rita

(ECM 2075)

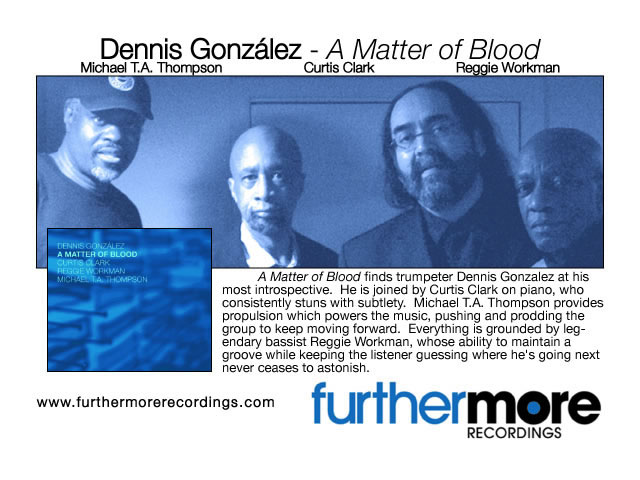

Anouar Brahem was dropped from the Penguin Guide to Jazz, and what miserable fudge there is in the passive form! We dropped him, though I don’t remember the logic, or who exactly made the decision. Fellow oud-player and ECM artist Rabih Abou-Khalil obviously passed muster. Perhaps Brahem was overlooked and the omission never queried. From a personal point of view, I find him most persuasive and most convincing as a jazz improviser when not forced into a familiar jazz context. One British journalist – perhaps it was John Fordham – proposed that Brahem was in advance of the cutting edge of ‘80s jazz and thus perhaps excluded from the usual lists.

Anouar Brahem was dropped from the Penguin Guide to Jazz, and what miserable fudge there is in the passive form! We dropped him, though I don’t remember the logic, or who exactly made the decision. Fellow oud-player and ECM artist Rabih Abou-Khalil obviously passed muster. Perhaps Brahem was overlooked and the omission never queried. From a personal point of view, I find him most persuasive and most convincing as a jazz improviser when not forced into a familiar jazz context. One British journalist – perhaps it was John Fordham – proposed that Brahem was in advance of the cutting edge of ‘80s jazz and thus perhaps excluded from the usual lists.

Whatever the case and whatever the underlying mood – ethnocentric, maybe – Brahem stands somewhat apart, even in ECM’s formidably un-doctrinaire catalogue. But try listening to The Astounding Eyes of Rita off the back of a recent diet of very early jazz and a lot of jazz guitar, which has been my recent regimen, and he immediately moves closer to the mainstream. It has something to do here with the sound of the oud, which combines harmonic richness with a light and mobile timbre and, still more, the very distinctive clomp of the darbouka, sometimes likened to the tabla, though only by the hearing-impaired: it’s open and clipped in the way tabla never is, and it serves a different purpose in the ensemble. Try “Stopover in Djibouti” for the best illustration, though here the voice that insists is that of Klaus Gesing’s bass clarinet. It has become one of the key solo instruments in contemporary jazz. Herbie Mann may have been the first to devote a whole record to it; there is no end of bass clarinet specialists – as opposed to doublers – around at the moment. Gesing is one of the best, largely because he never tries to make the instrument sound like a tenor saxophone with issues, but give it its own identity.

The other member of the group, along with Brahem and darbouka/bender player Khalid Yassine, is bassist Bjørn Meyer. He takes a greater share of rhythmic duties than a conventional jazz bassist, but also a more proactive role than merely touching in the bottom end of the harmony. In a sense, it is Meyer who determines the direction of these pieces, more obvious when the mood is calm, as on the two opening tunes.

Brahem has a unique ability to build an atmosphere that seems sufficient to the album or concert at hand. He did this with Conte de l’incroyable amour, his beautiful 1992 record for the label, a work very difficult to describe in any other terms than its own. He did it again on 2002’s Le Pas de chat noir, and it becomes evident here on the middle track of the album, the dream-like title piece. It’s possible to unpick the harmonic code and there’s nothing excessively virtuosic in the execution of any part, but I defy anyone to verbalize the total effect with any accuracy.

Brahem is, self-evidently, an instrumental master and a very major musician. Where he sits in plonky generic terms is neither here nor there. I like to think that his omission from that outsize book, with its basking-shark gape, was a kind of back-handed compliment.

–Brian Morton

Anthony Braxton

Creative Orchestra (Koln) 1978

hatOLOGY 2-644

This double CD set, finally available again, nicely complements the Arista Creative Orchestra Music 1976 album (included in the recent Mosaic box set) in that includes similar material played by an ensemble similar in scale and configurations; but coming after a string of concerts, this performance transmits both the excitement of a live evening and the relaxed approach of an ensemble that is familiar with the music. Electronics are provided by Bob Ostertag, his dramatic and cinematic approach widely different from Richard Teitelbaum's, the more familiar voice in the context of Braxton music; the contrast between the synthesizer solo and the big band romp in “Composition 51” makes for an unforgettable musical moment. Not that the acoustic instrumentalists are irrelevant, with brass soloists like Leo Smith, Kenny Wheeler, George Lewis and Ray Anderson, and youngsters like Marty Ehrlich, Ned Rothenberg and Vinny Golia in the woodwinds section. For many of the musicians, including pianist Marilyn Crispell, bassists John Lindberg and Brian Smith, and the mostly melodic Mr. Thrurman Barker on drums, this is one of their first major recordings. Notice that Braxton himself only conducts and does not play.

This double CD set, finally available again, nicely complements the Arista Creative Orchestra Music 1976 album (included in the recent Mosaic box set) in that includes similar material played by an ensemble similar in scale and configurations; but coming after a string of concerts, this performance transmits both the excitement of a live evening and the relaxed approach of an ensemble that is familiar with the music. Electronics are provided by Bob Ostertag, his dramatic and cinematic approach widely different from Richard Teitelbaum's, the more familiar voice in the context of Braxton music; the contrast between the synthesizer solo and the big band romp in “Composition 51” makes for an unforgettable musical moment. Not that the acoustic instrumentalists are irrelevant, with brass soloists like Leo Smith, Kenny Wheeler, George Lewis and Ray Anderson, and youngsters like Marty Ehrlich, Ned Rothenberg and Vinny Golia in the woodwinds section. For many of the musicians, including pianist Marilyn Crispell, bassists John Lindberg and Brian Smith, and the mostly melodic Mr. Thrurman Barker on drums, this is one of their first major recordings. Notice that Braxton himself only conducts and does not play.

The different atmospheres of the compositions segue nicely into each other, creating a great sense of flow: structured themes, solos and small-group improvised exchanges with colors floating in and out, instruments pitched against different backgrounds in a way that reminds of the pulse-track concerts. There's very little of what could be termed impressionistic arranging, no slowly swelling chords and cloud-like suspended sounds: the music is energetic, sharp and stomping, close to the manic discipline of Jim Europe, the inspirational vibe of Scott Joplin's Treemonisha and the intricate contrapuntal rhythms devised by Fletcher Henderson's arrangers – an impression reinforced by the earthy nature of the solos, especially by the trombone players, and by the place of honor given at the end to “Composition 58,” Braxton's rousing take on march music. While lacking the unique Faddis solo on piccolo trumpet, this version of 58 is almost twice as long, “unmitigated splendour” in annotator Graham Lock's words, with solos by George Lewis, Leo Smith, Ned Rothenberg and rain on the parade courtesy of Ostertag again. Be it for the nature of the concert, or for recording problems, both the piano and Birgit Taubhorn’s accordion play generally little part in the proceedings, compared to electronics and vibraphone. This is however among the first cooperations between Crispell and Braxton, so her brief solo outing during “Composition 51” must be considered successful, a serene section leading to a true “conference of the birds” for assorted flutes and followed by a lyrical solo by Kenny Wheeler where the accordion provides one of the background colors.

But a blow-by-blow account of everything happening on these CDs is impossible, and in fact every listen brings new discoveries: an excellent guidebook is Lock’s informative and insightful notes; their readability would benefit from a slightly larger font, at least for our aging section of the audience. Being slightly retentive, I hate packaging where CDs scratch on cardboard and are not in held firmly in place, so I immediately tape paper envelopes inside. Even more so now, after another Braxton hatART (Dortmund (Quartet) 1976, to boot!) developed some kind of scary rot which is gnawing at the silvery inside – check yours and make safety copies.

These small qualms aside, this is an essential set, one of the great record of creative music ensemble of all times, one of many achievements that firmly place Braxton among the great American masters, and a great introduction to his music.

–Francesco Martinelli

Peter Brötzmann

MLost & Found

FMP CD 134

Sonore

Call Before You Dig

Okkadisk OD12083

Peter Brötzmann’s music isn’t mellowing with age. The walls still tumble down when the saxophonist is at full bore, evidenced by ample portions of Lost & Found, which documents Brötzmann’s 2006 Nickelsdorf Konfrontationen solo concert, and Call Before You Dig, a 2-CD set of concert and studio recordings made at Cologne’s Loft. But, it can be said that Brötzmann’s music is ripening, and that his solo work and his co-op trio with Ken Vandermark and Mats Gustafsson bear this out best. He veers easily into “Crepuscule with Nellie” towards the end of the solo album, a gesture inconceivable thirty years ago. His tenor’s rasp is industrial compared to Charlie Rouse’s and his attack emphatically lacks Monk’s tender intentions; yet, Brötzmann’s reading is compelling because it is inscrutably true to the material. Sonore doesn’t quote, making less specific references instead; a riff-laden line for two clarinets has an almost Ellingtonian tang; murmured long tones wrap about variants of a “Blue Train”-like motive; throughout the collection, Brötzmann, Vandermark and Gustafsson have glancing encounters with the idiom, and a few head-ons as well.

Peter Brötzmann’s music isn’t mellowing with age. The walls still tumble down when the saxophonist is at full bore, evidenced by ample portions of Lost & Found, which documents Brötzmann’s 2006 Nickelsdorf Konfrontationen solo concert, and Call Before You Dig, a 2-CD set of concert and studio recordings made at Cologne’s Loft. But, it can be said that Brötzmann’s music is ripening, and that his solo work and his co-op trio with Ken Vandermark and Mats Gustafsson bear this out best. He veers easily into “Crepuscule with Nellie” towards the end of the solo album, a gesture inconceivable thirty years ago. His tenor’s rasp is industrial compared to Charlie Rouse’s and his attack emphatically lacks Monk’s tender intentions; yet, Brötzmann’s reading is compelling because it is inscrutably true to the material. Sonore doesn’t quote, making less specific references instead; a riff-laden line for two clarinets has an almost Ellingtonian tang; murmured long tones wrap about variants of a “Blue Train”-like motive; throughout the collection, Brötzmann, Vandermark and Gustafsson have glancing encounters with the idiom, and a few head-ons as well.

Still, it would overstatement to suggest that overwhelming primordial intensity is no longer the center of Brötzmann’s aesthetic, or that his occasional forays into more jazzcentric zones compensate for flagging energies. The quarter-hour alto solo that opens the Nickelsdorf set is classic Brötzmann and ranks among his very best outings on the horn, a captivating and surprisingly refreshing squall. His tarogato solo is even more raw and unnerving. Few know how to spur Brötzmann like Vandermark and Gustafsson; they repeatedly trigger torrential passages in which Brötzmann matches their most athletic, even pugilistic playing, blow for blow. Even though the three have been the front line core of Brötzmann’s Chicago Tentet for its decade-plus run, the trio setting allows for shifts in their interplay to be fully heard that simply don’t register in some of the Tentet’s more blistering tuttis. Subtlety is often not the objective in such passages; instead, they streamline and even magnify the music’s power. Although it may seem to some that it is occurring at a glacial pace, Brötzmann is evolving. Both Lost & Found and Call Before You Dig testify to that.

–Bill Shoemaker

Elton Dean’s Ninesense

Happy Daze/Oh! For the Edge

Ogun OGCD 032

Saxophonist Elton Dean kept his little big band together from 1975 to 1978, recording the two terrific Ogun albums reissued here in ’76 and ’77. There’s a resemblance to Chris McGregor’s Brotherhood of Breath, partly because at one time or another every member of Ninesense (with the exception of pianist Keith Tippett) had also occupied a chair in the South African pianist’s obstreperous orchestra. But the South African influence is only one of many. In their individual careers, the members of Ninesense routinely crossed over genre boundaries. Dean worked in the Canterbury rock band Soft Machine, for instance, while trumpeter Mark Charig and trombonist Radu Malfatti played with a host of European free improvisers. As a consequence, the lingua franca of Ninesense, as well as many other British free jazz albums of the period, can claim sound roots in the vocabularies of free improvisation, rock, and jazz.

Saxophonist Elton Dean kept his little big band together from 1975 to 1978, recording the two terrific Ogun albums reissued here in ’76 and ’77. There’s a resemblance to Chris McGregor’s Brotherhood of Breath, partly because at one time or another every member of Ninesense (with the exception of pianist Keith Tippett) had also occupied a chair in the South African pianist’s obstreperous orchestra. But the South African influence is only one of many. In their individual careers, the members of Ninesense routinely crossed over genre boundaries. Dean worked in the Canterbury rock band Soft Machine, for instance, while trumpeter Mark Charig and trombonist Radu Malfatti played with a host of European free improvisers. As a consequence, the lingua franca of Ninesense, as well as many other British free jazz albums of the period, can claim sound roots in the vocabularies of free improvisation, rock, and jazz.

The ensemble work in Ninesense was more contained than BoB’s loosely knit uproar, but none the worse for that. A big part of the joy and power of Ninesense lies in their enthusiastic precision in executing Dean’s compositions. As a composer, Dean always had very well defined aims; he didn’t simply write heads and then let everyone solo on every tune. He deployed different techniques and tapped different soloists for each piece. For instance, “Nicrotto,” which opens the band’s debut album, Oh, For the Edge, emphasizes the band’s brass section in dark, monolithic ensemble motifs embroidered by Miller and Tippett. Tippett and trombonists Nick Evans and Radu Malfatti are the only soloists. On the other hand, “Seven for Lee,” a sort of a South Africa/Brass modal groove tune, plays the band’s reed and brass sections against one another in classic big band style. Dean and trumpeter Harry Beckett are featured soloists. Dean maintains his broad range and tight focus on Happy Daze, recorded live at 100 Club a year later. Collective improvisations grow out of a loose and volatile ensemble on “Forsoothe.” “Dance” is a fast melody that lets Tippett, Miller, and Moholo – surely one of the greatest jazz rhythm sections of all time – light a good, hot fire under the band.

Of course the ensemble brio is only half the story. This is a band of superb soloists who were all at early and vibrant peaks in their careers. Dean is featured most often on both discs, but is in especially good form on Happy Daze. He has a fat alto sound, a touch raspy, but always warm and with a vocal quality in the upper register. It’s also worth noting that it’s not entirely a jazz sound, although obviously most heavily indebted to jazz. Maybe the blues isn’t as much a part of its DNA, maybe it’s the particular mix of influences current among the British players at the time, but there is an indefinable quality that marks it as a British free jazz voice and not an American one. (This is noted with approval, by the way.) On “Sweet F.A.,” Tippett, with his crystalline articulation, takes a ballad solo glittering with brilliant lines and sparkling chords. “Dance” is a rousing showcase for the explosive phrasing of the mercurial Evans.

This is wonderful music in which exciting new discoveries contributed to an emerging uniquely British musical identity. It’s full of fire and optimism and ferocious imagination, a willingness to tackle the enormous challenge of forging a new music. Ninesense was one of Dean’s greatest achievements.

–Ed Hazell