Moment's Notice

Reviews of Recent Media

(continued)

Alexander von Schlippenbach

Globe Unity

CvsD CD091

It is ironic that the music which signaled one of the turning points towards a robustly European form of free jazz was commissioned from pianist Alexander von Schlippenbach by RIAS, the American radio station in Berlin. It allowed Schlippenbach the chance to realize large ensemble works which replicated the unfettered freedom and energy he was exploring in small groups, allied to the new music procedures which he had studied with German composer Bernd Alois Zimmerman. First performed at the Berlin Jazz Festival in November 1966 to a mixed critical reception, the two pieces were recorded the following month and subsequently released under the title Globe Unity on the SABA imprint.

It is ironic that the music which signaled one of the turning points towards a robustly European form of free jazz was commissioned from pianist Alexander von Schlippenbach by RIAS, the American radio station in Berlin. It allowed Schlippenbach the chance to realize large ensemble works which replicated the unfettered freedom and energy he was exploring in small groups, allied to the new music procedures which he had studied with German composer Bernd Alois Zimmerman. First performed at the Berlin Jazz Festival in November 1966 to a mixed critical reception, the two pieces were recorded the following month and subsequently released under the title Globe Unity on the SABA imprint.

Schlippenbach constructed his 13-strong ensemble around the core of two extant units: the Manfred Schoof Quintet, of which he was part as well as being the prime composer, alongside tenor saxophonist Gerd Dudek, bassist Buschi Niebergall, and drummer Jaki Liebezeit, and the Peter Brötzmann Trio with bassist Peter Kowald and drummer Mani Neumeier. The album gives the first glimpse of iconoclasts such as Brötzmann and Kowald on record, alongside a host of others who would go on to become leading lights on the scene including Gunter Hampel, Willem Breuker, and Karl Berger.

At the time there was no precedent for such developments in Europe, and precious little across the Atlantic either. Perhaps the nearest comparator would be the Jazz Composer’s Orchestra, whose Communication was issued the previous year, while Coltrane’s Ascension was released in February 1966, and Cecil Taylor’s Unit Structures in October of that year. But none of these offers anything like the same organic flux between free improvisation and organized orchestral polyphony heard on Globe Unity. As explicated in the original liner notes, reproduced in the gatefold sleeve of CvsD’s exemplary reissue, although Schlippenbach derived the music from a twelve-tone row, he firmly identified the result as jazz, only realizable by jazz improvisers.

“Globe Unity,” the name of the composition on the A side, comprises a series of orchestral voicings, sometimes fluttering or moving in loose shapes stemming from graphic notation, at other times more clearly notated into slow moving harmonies, from which emerge episodes for the main soloists, here Brötzmann on alto, Dudek on tenor, Schoof on trumpet, and Schlippenbach himself. Brötzmann’s already distinctive squealing invective soars and snags, supported by just Kowald and Neumeier at first, then with exclamatory piano chords and low horn blasts, and brass counterblasts in a contrast of the wild and the inexorable. Schlippenbach creates such differing settings around each of the soloists, including a series of rising and falling glissandi cosseting Dudek’s careening wail. Though played fast and high, the machine gun stutter of Schoof’s trumpet most clearly harkens back to previous eras in what is a creditable outing, though without the sort of radical effects used so devastatingly by the reedmen. Schlippenbach’s percussive piano, with its echoes of Taylor, is on display throughout, peaking in an aggressive clanking attack, flanked by dual basses and airy cymbals. Even so he still manages to orchestrate layers of reed and brass, culminating in a unison restatement of the slow-moving harmonic “theme” to cap an absolutely wonderful journey. With the modern-day prevalence of musicians schooled not only in free improvisation but also new music, this work possibly sounds more contemporary now than it did at the time, when such a marriage was both new and viewed with suspicion by sections of the jazz establishment.

If the first side represents a triumph of synthesis, and ultimately ushers in fertile ground for investigation over the coming years, “Sun” with its exotica and world music inflections has not aged quite as well. As such innovations have been dramatically surpassed and extended with ever greater authenticity over the intervening decades, the effects consequently sound more of their time. Nonetheless it’s still an engaging prospect. Almost everyone supplements their main axe with percussion devices or novel wind instruments to conjure an atmospheric opening, in which Kowald’s resonant pizzicato and Niebergall’s wheezing arco supports Schlippenbach’s keyboard sweeps. In spite of the twin drum/bass axis, this cut remains largely rubato, without the pulsating drive of the title track, but still allows the assembled cast a sequence of unconstrained solos with sparse textural backing, of which Hampel’s throaty yodeling bass clarinet is the most attributable, interspersed with occasional orchestral tutti. It’s not until almost the end that a deliberate unison line materializes, before the piece returns to the exotic as colorful cries surrounding a bass/drum interchange with Neumeier’s tablas prominent. In both pieces Schlippenbach uses tubular bells to cue transitions, but it’s an intrusive mechanism which outstays its welcome. Happily, he developed less obvious means for ensemble orchestration in subsequent works.

The difficulty of large group free improvising can be discerned from the relatively few who’ve persisted for any duration (although clearly economics is at least as significant a factor in maintaining such outfits long enough to develop an understanding). This group eventually assumed the title Globe Unity Orchestra, initially under Schlippenbach’s direction, but with Kowald also at the helm for a stint. While composed material, including from guests such as Steve Lacy and Anthony Braxton, informed their early recordings, they later pivoted to discarding written props entirely. As time has passed opportunities to reunite have become increasingly sporadic, but have even so encompassed a series of anniversary albums, of which Globe Unity 50 Years (Intakt, 2018) is the most recent.

For anyone interested in the history of European free jazz, Globe Unity, particularly the title track, remains an essential document. But more than that, unlike many seminal recordings it retains both its freshness and even more important listenability, even 56 years on.

–John Sharpe

Archie Shepp

Fire Music to Mama Too Tight Revisited

ezz-thetics 1136

One of the great things of the ezz-thetics Revisited Series is that is a great way to catch up on music I haven’t heard in a long time, discover new records, or fill out gaps in my collection with albums that are long out of print that I have either never been able to find or could afford. This double dip into Archie Shepp’s mid-60s Impulse catalog is example nonpareil of the series’ importance for me: this was my first encounter with Mama Too Tight (1967) and it had been ages since my LP of Fire Music (1965) hit the turntable.

One of the great things of the ezz-thetics Revisited Series is that is a great way to catch up on music I haven’t heard in a long time, discover new records, or fill out gaps in my collection with albums that are long out of print that I have either never been able to find or could afford. This double dip into Archie Shepp’s mid-60s Impulse catalog is example nonpareil of the series’ importance for me: this was my first encounter with Mama Too Tight (1967) and it had been ages since my LP of Fire Music (1965) hit the turntable.

Fire Music, is, well, a classic. If one could only have one Shepp album in their collection, I wouldn’t argue against anybody who said this was it. A sextet date with Marion Brown, Ted Curson, Joseph Orange, Reggie Johnson, and Joe Chambers, Fire Music was the follow up to Shepp’s debut for Impulse, Four for Trane. It marks a growth in Shepp’s compositional ambitions and voice, as his charts show range and complexity; they are more than just heads harmonized for four horns. One hears both the influences of Ellington and Mingus and there’s a taught push and pull between the solo and the ensemble throughout. The album’s centerpiece is “Hambone,” which opens the album. With a series of different themes that range from declarative and bold to chaotic and sober, Shepp creates a set piece for each horn player. Curson blows over a charging, angry, waltz horn figure; Brown swaggers over a sly medium swing; Orange is somewhat relaxed, as his setting is similar to Brown’s. Where Curson sounded as if he was just a slip up away from being swallowed by the ensemble, Shepp blows with fire, quickly putting distance between him and the rest of the band. The head themes return just before Shepp loses his mates for good. Shepp’s arrangement of Ellington’s “Prelude to a Kiss” has the same drama and presence as the genuine article and makes the band sound much larger than a sextet, while his solo conjures the soul of Hodges and Webster. "The Girl from Ipanema” has a bright, almost big band feel, perhaps due to Chambers’ driving kicks, accents, and fills. Here, Shepp stretches out to take the longest solo on the album, taking his time and keeping the speedometer at a nice and easy 45 mph. A Sunday drive in Brazil. With its spoken word and tenor/bass/drums configuration (David Izenzon and J.C. Moses), “Malcolm, Malcolm, Sepmer Malcolm” always stuck out from the rest of the album. On the ezz-thetics edition it has been moved to the last track on the album, making that out-of-place feeling even more exaggerated.

Recorded about eighteen months after Fire Music – a stretch during which Shepp released On This Night, New Thing at Newport, and Live in San Francisco – Mama Too Tight is a similarly scintillating mix of Shepp originals and covers. The whole of side A is the epic “A Portrait of Robert Thompson (As A Young Man).” Here Shepp shows his compositional growth since Fire Music. The transitions between sections are somehow both nuanced and unexpected. The shift from the frenzied opening – which features a wild and fiery Shepp rocked by blasts and bellows from tubist Howard Johnson and trombonists Roswell Rudd and Grachan Moncur III, and Beaver Harris’s loud and active drums – to a new arrangement of “Prelude to a Kiss” is instantaneous, unexpected, and arresting. Later, a free jazz blowout quickly morphs into a march that is first comic and then heads out for Sousa territory. Somehow, none of it feels forced or incongruent. The title track is a grooving thirteen-bar blues that lives somewhere between Lee Morgan’s “The Sidewinder,” James Brown, and a free jazz jam session. Like the two “Preludes” heard earlier on the disc, Shepp’s arrangement of Fred Lacey’s lush ballad “Theme for Ernie” is a continuation of his rough and ready take on Ellingtonia – as if the Duke’s band stopped shaving for a month or two (although the switch to a Latin feel at the end is a curious choice). The album closes with “Basheer,” a sprawling and raucous ten-minute work that sounds Mingus-y in its approach. There are multiple themes, hints at themes, free-wheeling blowing over written counter ensemble lines, a Tommy Turrentine solo backed by long held horn chords, and simultaneous soloing where voices surge and scream to the top and recede. The piece often sounds as if it’s held together with scotch tape and hope – nearly always a recipe for excitement.

The ezz-thetics edition’s remastering of Fire Music far outpaces the sound quality of my slightly beat up first pressing: the music is crisp, clear, and punchy, although I do not know how it compares to the mid-90s Impulse reissue. The sound quality on Mama Too Tight is similarly excellent. While Fire Music and Mama Too Tight aren’t as hard to find as other albums in the Revisited series, their pairing on one great sounding disc makes discovering or revisiting (no pun intended) two of Shepp’s great works pretty easy.

–Chris Robinson

Tyshawn Sorey Trio + 1 with Greg Osby

The Off-Off Broadway Guide to Synergism

Pi Recordings 96

Over the last several years, the well-deserved attention that Tyshawn Sorey’s music has gotten has tended to focus on his long-form composition and contributions to new music. The recipient of a Macarthur “genius” grant, Sorey has long been more than just a phenomenal percussionist. So it may be a bit of a surprise to some that his latest release is a three-disc whopper filled with standards. The Off-Off Broadway Guide to Synergism is filled with three sets recorded live at New York’s Jazz Gallery, pairing Sorey’s regular trio (including pianist Aaron Diehl and bassist Russell Hall) with alto whiz Greg Osby. Intended as a companion release to Mesmerism, from earlier this year, it’s a genuinely breathtaking release, filled with constant surprise and invention.

Over the last several years, the well-deserved attention that Tyshawn Sorey’s music has gotten has tended to focus on his long-form composition and contributions to new music. The recipient of a Macarthur “genius” grant, Sorey has long been more than just a phenomenal percussionist. So it may be a bit of a surprise to some that his latest release is a three-disc whopper filled with standards. The Off-Off Broadway Guide to Synergism is filled with three sets recorded live at New York’s Jazz Gallery, pairing Sorey’s regular trio (including pianist Aaron Diehl and bassist Russell Hall) with alto whiz Greg Osby. Intended as a companion release to Mesmerism, from earlier this year, it’s a genuinely breathtaking release, filled with constant surprise and invention.

It might appear daunting on the face of it, nearly four hours of music, three seamless, ever-flowing sets that morph in and out of tunes, many of which reach towards 15 or 20 minutes. But if you’re anything like me, you’ll quickly grow obsessed with it. I’ve basically had it on constantly over the last month, marveling at just how damn good the trio is in terms of what I want from jazz. Nimble and forceful, swinging and abstract, prodding and in the pocket, it’s all there. Not only do they know all these tunes just inside and out, they’re so attuned to each other’s nuances that they swap roles constantly and create the most fascinating counter-rhythms, or layers, or color washes, and always more than you might be able to process at a single moment. And we get Osby on top of that? Whew.

With the exception of Osby’s “Please Stand By,” every title in these sets will be recognizable. “Night and Day,” “Chelsea Bridge,” Ornette’s “Mob Job,” Tyner’s “Contemplation,” and a bevy of other platforms for this outrageously good band. I write that deliberately, as it’s perhaps only the titles that’ll be recognizable. Themes, harmonies, rhythms, they’re all there, make no mistake. But the prodigious invention that the band brings to each moment is utterly surprising (and throughout, you can hear the musicians themselves exulting). Even if you think you never need another standards record in your life, you’ll be knocked sockless as I was.

With so much music, a forensic recount isn’t feasible. Some key features, though, are worth pointing out. First of all, in case anyone has forgotten, Sorey has roots and swing just forever. Blistering double-time, deep pocket earthiness, every detail grounded in a superb touch and feel, not least with his sublime brushwork. In every tune here – and really, it’s just a single sustained performance – there’s so much going on that new details emerge on each listening. Consider Diehl’s gorgeous introduction to the first version of “Three Little Words,” a lovely and abstract approach that’s a cosmos away from Sonny Rollins or whichever version you’re most familiar with. As you listen, you sink in, aware that change is roiling all around: tasty tone-morphing from Osby, mercurial shifts in tempo or dynamics, telepathic interplay at the heart of it all.

You find yourself seemingly miles away from the song, and there’s the theme again, or perhaps a circus-music quote, or the tastiest contrast between bright melody and dark harmony. A dark Trane vamp here, a creeped-out “Chelsea Bridge,” and the most colossal solos (check out Diehl’s heartfelt turn on Andrew Hill’s “Ashes” or Hall’s lovely groaning on the Tyner tune). There’s more, more, always more. Pages of notes taken over a long period of immersion seem insufficient to convey just how consistently this band achieves full lift-off, often as if there are several different takes on the tune being played simultaneously. And before you know it, you’re somehow in the middle of “Ask Me Now,” or a tile-melting “Jitterbug Waltz,” or an unaccompanied Osby solo. At its most frothy – the punishing groove on the second version of “Please Stand By,” all those ostinati and Sorey’s outrageously nimble double-time – there’s still a ton of space and listening in this music. And at its most balladic, as on the epic “It Could Happen to You,” there’s huge tension and intensity.

Live in the space this band creates. Marvel at them taking on “Solar” or “I Remember You” and every atom of the jazz universe that strikes their fancy. My overriding impression is that this music absolutely deserves to be heard and encountered on that scale. It’s quite simply everything I love about jazz music, not so much a record of standards being taken way far out as it is a documentation of what sounds for all the world like eternal sound, with standards crystallizing it episodically. Simply stunning, the record of the year.

–Jason Bivins

Spaces Unfolding

The Way We Speak

Bead 43

Bead is a now-legendary musician-administered label that began in the early 1970s, an early outlet for London-based improvisers emerging in the wake of the first lions like Derek Bailey, Evan Parker, and John Stevens. Some earlier releases like Fire Without Bricks by drummer Roy Ashbury and saxophonist Larry Stabbins, and Philipp Wachsmann’s overlooked solo gem for violin and electronics, Writing in Water, have been reissued on CD by Corbett vs. Dempsey. Otherwise, it does take some effort to find Bead’s titles on LP, and only slightly less so with their CD catalog. With everything that happened in the 1970s now ripe for half-century reassessment, Bead should be celebrated in a new light, as the label championed a host of musicians who vividly fleshed out the history of the decade.

Bead is a now-legendary musician-administered label that began in the early 1970s, an early outlet for London-based improvisers emerging in the wake of the first lions like Derek Bailey, Evan Parker, and John Stevens. Some earlier releases like Fire Without Bricks by drummer Roy Ashbury and saxophonist Larry Stabbins, and Philipp Wachsmann’s overlooked solo gem for violin and electronics, Writing in Water, have been reissued on CD by Corbett vs. Dempsey. Otherwise, it does take some effort to find Bead’s titles on LP, and only slightly less so with their CD catalog. With everything that happened in the 1970s now ripe for half-century reassessment, Bead should be celebrated in a new light, as the label championed a host of musicians who vividly fleshed out the history of the decade.

Wachsmann continues to be a pillar of the label as an administrator as well as one of its primary artists. The quality of his distinctive voice is clearly presented on the aptly titled The Way We Speak by the cooperative trio, Spaces Unfolding. The album is a first, as it documents Wachsmann in a small group with flutist Neil Metcalfe, another longtime and under-heralded contributor to the arc of improvised music in the UK. The trio is rounded out by drummer Emil Karlsen, a relative newcomer to the scene, but who has quickly established himself as a resourceful improviser. Karlsen’s use of a small kit that recalls Stevens’ allows him to deftly color, texture, and propel the music as it develops.

Both Wachsmann and Metcalfe gravitate towards building complementary lines and timbres to create a freely contrapuntal interplay. They also both build materials without jump cuts or other discontinuity-producing devices. In this sense, their approach is consonant with the ensemble’s name. The unhurried pace of their five improvisations gives each improviser room to elongate short motive-like phrases, extend and morph dialogue, and carefully shade spaces – or leave them bare. It also gives the listener second-by-second insight into the close listening they share. This is enhanced by the excellent sound, achieved by recording in Old Saint Mary’s Church in Stoke Newington.

British people use the word “lovely” to describe almost anything – “brilliant” runs a close second. But both arguably overused descriptors apply to The Way We Speak. Spaces Unfolding’s music is something to savor, to relish. It is both lovely and brilliant.

–Bill Shoemaker

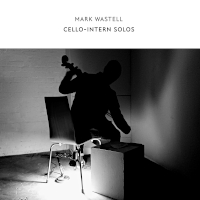

Mark Wastell

Cello-intern Solos

Confront Core 27

In February 2022, Mark Wastell began an ongoing series of late afternoon cello solos on the first Saturday of the month at London’s Hundred Years Gallery. The fundamental idea is, as he puts it, “No pressure. This is not a gig. To play regardless of whatever else is going on in the space. Develop a new method. Sounds. Movement. Make mistakes. Listen. Learn. Leave.” Or, as gallery director Graham MacKeachan puts it, “An activity. Not a concert. A process. Not a rehearsal. A passage. Not a performance. An application.” Over the course of 60 minutes, Cello-intern Solos documents 17 pieces from the series, recorded between February and May, the shortest around a minute and a half and the longest just shy of seven minutes long. While the act of selecting and sequencing recordings for release is quite different than the monthly activity, the accrual of the pieces on this recording reveal Wastell’s singular focus and commitment to exploring the elemental sounds of his instrument.

In February 2022, Mark Wastell began an ongoing series of late afternoon cello solos on the first Saturday of the month at London’s Hundred Years Gallery. The fundamental idea is, as he puts it, “No pressure. This is not a gig. To play regardless of whatever else is going on in the space. Develop a new method. Sounds. Movement. Make mistakes. Listen. Learn. Leave.” Or, as gallery director Graham MacKeachan puts it, “An activity. Not a concert. A process. Not a rehearsal. A passage. Not a performance. An application.” Over the course of 60 minutes, Cello-intern Solos documents 17 pieces from the series, recorded between February and May, the shortest around a minute and a half and the longest just shy of seven minutes long. While the act of selecting and sequencing recordings for release is quite different than the monthly activity, the accrual of the pieces on this recording reveal Wastell’s singular focus and commitment to exploring the elemental sounds of his instrument.

Across all of the instruments that he plays, from bass to cello to tam-tam and percussion, Wastell zeros in on their micro-textures and mercurial timbres and that keen ear informs his playing throughout. Here, his consummate command of the cello is in evidence as he plies threads against each other, spidering out in whorls of overlapped kernels which he weaves together with a compact sense of structure. But technique never overwhelms that structural sensibility. Each piece stands as a cogently conceived statement while fitting seamlessly into the overall flow of the release. From the first notes, it is clear that the gallery itself is also a key collaborator in this process. There’s a close resonance, allowing Wastell’s arco overtones, harmonics, and abraded textures to hang a bit, reverberating against each other. And there are also the ambient sounds of footsteps and conversations of people in the gallery that wafts through the recordings, placing the music in a specific locational sense of space. Amazingly, as far as I can tell, this is Wastell’s first solo cello recording in his three decades of playing. One certainly hopes this is not the last.

–Michael Rosenstein