Moment's Notice

Reviews of Recent Recordings

(continued)

Susan Alcorn Quintet

Pedernal

Relative Pitch Records RPR1111

After a slew of solo releases and a run of high-profile collaborations with the likes of Mary Halvorson, Ken Vandermark, and Nate Wooley, pedal steel guitarist Susan Alcorn finally presents her first album as a band leader. It’s been a long time coming, given that she embarked professionally in the 1970s, although it wasn’t until the late ‘90s that she swerved into left field. For Perdernal, she assembles a quintet made up of some of her closest associates. Alongside Halvorson, she includes fellow Baltimore alum bassist Michael Formanek, drummer Ryan Sawyer and violinist Mark Feldman, on a program of five originals.

After a slew of solo releases and a run of high-profile collaborations with the likes of Mary Halvorson, Ken Vandermark, and Nate Wooley, pedal steel guitarist Susan Alcorn finally presents her first album as a band leader. It’s been a long time coming, given that she embarked professionally in the 1970s, although it wasn’t until the late ‘90s that she swerved into left field. For Perdernal, she assembles a quintet made up of some of her closest associates. Alongside Halvorson, she includes fellow Baltimore alum bassist Michael Formanek, drummer Ryan Sawyer and violinist Mark Feldman, on a program of five originals.

Alcorn’s writing, like her playing, defies easy categorization, pitched somewhere between modern jazz, contemporary classical, and free improvisation, but with forays into noise, folk, and C&W. As a result, hummable tunes rub shoulders with knotty group interplay and drifting impressionism, but always in the service of a palpable composerly intent. Alcorn chose her partners wisely as not only do they breathe unruly life into her complex charts, but also expertly exploit the fleeting improvisational spaces they contain.

Fittingly it’s Alcorn’s voice which grabs the attention. She commences the title track accompanied only by Formanek’s surefooted pizzicato, showcasing an exquisite amalgam of luminous bent notes, chiming twang, and ethereal reverb. Named after the iconic New Mexico mesa celebrated by Georgia O’Keefe, the folky sweep of the title piece conjures wide open vistas. Once flanked by Halvorson and Feldman, Alcorn switches up a gear, gradually spinning the song out of shape, before squally exchanges with Halvorson and an ultimately courtly restatement of the theme.

Alcorn’s scripts thrive on unexpected turns and combinations. Inspired by Anasazi dwellings in Utah’s Hovenweep National Monument, “Circular Ruins” is suitably enigmatic, while “R.U.R.” is sprightly with a jaunty unison. “Night In Gdansk” is once again more mysterious, comprising a series of densely plotted episodes, melding together dynamic ensemble interaction, warmly enveloping melodicism, and sudden outbursts of individual expression, with Alcorn’s haunting shimmer on occasion placing the titular Polish port in some proximity to Messiaen’s “From The Canyon To The Stars.”

After a false start and some studio banter, “Northeast Rising Sun” morphs from a Sufi-influenced refrain into a joyous C&W hoedown. Like the opener, it begins with Alcorn alone, paced by a handclapped rhythm from the band. Everyone gets to strut their stuff, with Feldman reprising his Nashville roots, before a reprise takes out the record on an uplifting note, which serves to highlight Alcorn’s bewitching mix of astringent abstraction and toothsome sweet spots even more clearly.

–John Sharpe

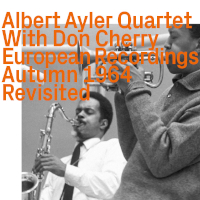

Albert Ayler Quartet with Don Cherry

European Recordings Autumn 1964 Revisited

ezz-thetics 1107

Between February and November of 1964 Albert Ayler made a series of studio, live, and radio recordings that went on to yield seven albums, including the seminal Spiritual Unity. Trying to sort out and keep track of these, however, can be a tricky affair, since many of them have been released and rereleased – occasionally with questionable business practices – by multiple labels. Some have appeared under different titles with different cover art, making it even more difficult to follow. It’s a bit of a quagmire.

Between February and November of 1964 Albert Ayler made a series of studio, live, and radio recordings that went on to yield seven albums, including the seminal Spiritual Unity. Trying to sort out and keep track of these, however, can be a tricky affair, since many of them have been released and rereleased – occasionally with questionable business practices – by multiple labels. Some have appeared under different titles with different cover art, making it even more difficult to follow. It’s a bit of a quagmire.

In the last few years, ezz-thetics has brought back five of seven of Ayler’s 1964 albums:

- Spirits aka Witches and Devils (recorded February in New York; featuring Norman Howard, Henry Grimes, Earle Henderson, and Sunny Murray)

- Prophecy (rec. June in New York; featuring Gary Peacock and Murray)

- Copenhagen Tapes (rec. September in Copenhagen; featuring Don Cherry, Peacock, and Murray)

- Ghosts aka Vibrations (rec. September in Copenhagen; featuring Cherry, Peacock, and Murray)

- Hilversum Session (rec. November in Hilversum, the Netherlands; featuring Cherry, Peacock, and Murray)

The final three albums were recorded while Ayler’s Quartet was in the middle of a string of engagements in Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands. In 2016 hatology reissued the Hilversum Session along with three studio tracks from Copenhagen Tapes as European Radio Studio Recordings 1964. The following year they released six live cuts from Copenhagen Tapes – which also appeared in Revenant’s 2004 Holy Ghost box set – in 2017 as Copenhagen Live 1964. Which brings us to this release: European Recordings Autumn 1964 Revisited. This two-disc set combines the Copenhagen and Hilversum releases in one convenient package. Released with permission of the Ayler estate, it is essentially a reissue of a two very recent reissues. Listeners owning both hatology reissues will find no new music here.

Oddly enough, this set is organized in reverse chronological order, with the second disc containing the earliest recordings, which were put to tape live at Club Montmartre, Copenhagen. While the date here is listed as September 26, the earlier hatology reissue, the Holy Ghost box set, and the online Ayler discography all list the date as September 3. The first six cuts on disc one encompass the November 6 session for VARA Radio, while the disc’s final three cuts are from September 10 recordings for Danish radio in Copenhagen.

Cherry had just joined Ayler that July and would only remain with him through November, after which he was replaced by Donald Ayler. Despite its short life, this quartet played some of most vital music of Ayler’s catalog. One hears that the band had yet to work out its identity or fully define Cherry’s role. On the second disc Ayler would jump into the head, giving Cherry seemingly no warning, causing Cherry to miss the entrance. At other times, as on the opening track “Spirits,” Cherry would play behind and alongside Ayler’s solos, but it wasn’t clear what his role was. It is as if Ayler is there, so is Cherry. They are not exactly together, but that’s ok.

Throughout each of the three sessions, Ayler’s playing is especially inspired, ferocious, and urgent: a mix of his trademark runs, honks, chortles, cries, and swoops, all conveyed by that huge sound and wide vibrato. He plays as if this was his last chance to get it all out. Cherry, by contrast, tends to be slightly more reserved and he works out ideas more methodically and deliberately. As they demonstrated on Spiritual Unity and their other work with Ayler from the period, Peacock and Murray mastered the approach to time and tempo where each is to be implied and stretched rather than kept.

By the time the Hilversum session came around in November, the band had grown. Cherry was not caught off guard by the restatements of the tunes, and his playing was more present and assured when playing with Ayler. The band’s book had apparently grown as well, and now included Cherry’s bright and playful composition “Infant Happiness.” Based on short, catchy phrases that invite an elastic approach to time, it fit right in with Ayler’s compositions. “Angels” is a weighty lament. Ayler begins his solo with lower, somber notes but then quickly unleashes torrents of notes. Cherry provides a great contrast, moving at a slower pace. “C.A.C.” is a boisterous and raucous tune that quickly transitions into a maelstrom, as if the tune was getting in the way of what the band really came to do. The only overlap between Hilversum and the live Montmartre date is “Spirits,” making each set distinct from the other. Each of the three compositions from the studio Copenhagen sessions – “Vibrations,” “Saints,” and “Spirits” – were on the Montmartre set list, so they are more like bonus tracks rather than a standalone set.

At its core, European Recordings documents one of Ayler’s best bands – and arguably one of the finest bands of the era – developing its vocabulary and coming in to its own. It’s impossible to say what this quartet could achieve had it stayed together and if Ayler had the financial and marketing support that his music warranted. However, this and the other excellent hatology/ezz-thetics reissues of Ayler’s 1964 recordings, make it easier to enjoy, understand, and work through a particularly fruitful period of Ayler’s career.

–Chris Robinson

Derek Bailey + Mototeru Takagi

Live at FarOut, Atsugi 1987

NoBusiness Records NBCD 132

The Lithuanian NoBusiness label pulls another gem from the vaults with the release of this previously unissued live recording of Derek Bailey and Japanese reed player Mototeru Takagi, recorded live in 1987 at FarOut, Atsugi, Kanagawa, Japan. Part of the initial group of Japanese free jazz players, Takagi ought to be far better known than he is. Starting out in percussionist Motoharu Yoshizawa’s trio in 1968, Takagi went on to play with key Japanese free improvisers like Masahiko Togashi, Masayuki Takayangi, Motoharu Yoshizawa, Itaru Oki, Toshinori Kondo and Sabu Toyozumi. From the late ‘60s on, this community of musicians began charting a collective approach to uncompromising freedom, increasingly collaborating with visiting free players from Europe and the US. Takagi was amongst those tapped when Milford Graves visited Japan in 1977 (documented on the album Meditation Among Us) and when Derek Bailey visited in 1978 (documented on the album Duo & Trio Improvisations). Bailey returned to Japan a number of times after that 1978 meeting, including the tour that resulted in this recording.

The Lithuanian NoBusiness label pulls another gem from the vaults with the release of this previously unissued live recording of Derek Bailey and Japanese reed player Mototeru Takagi, recorded live in 1987 at FarOut, Atsugi, Kanagawa, Japan. Part of the initial group of Japanese free jazz players, Takagi ought to be far better known than he is. Starting out in percussionist Motoharu Yoshizawa’s trio in 1968, Takagi went on to play with key Japanese free improvisers like Masahiko Togashi, Masayuki Takayangi, Motoharu Yoshizawa, Itaru Oki, Toshinori Kondo and Sabu Toyozumi. From the late ‘60s on, this community of musicians began charting a collective approach to uncompromising freedom, increasingly collaborating with visiting free players from Europe and the US. Takagi was amongst those tapped when Milford Graves visited Japan in 1977 (documented on the album Meditation Among Us) and when Derek Bailey visited in 1978 (documented on the album Duo & Trio Improvisations). Bailey returned to Japan a number of times after that 1978 meeting, including the tour that resulted in this recording.

When Bailey returned in 1987, he played some solos, duos with dancer Min Tanaka, and in a trio with Peter Brötzmann and percussionist Sabu Toyozumi as well as in this duo session with Takagi. The reed player sticks to soprano saxophone across the four expansive duos, a half hour opener, two 17-minute pieces, and a relatively compact 8-minute foray. Bailey’s electric guitar playing is in top form throughout, his lightning, refracted angular phrasing bursting with brittle resonance. One can readily hear why Bailey gravitated to Takagi. The reed player immediately hits with an acidic attack, starting with long tones that ring against Bailey’s harmonics, patiently building to lithe, spiky intensity. It’s always great to hear Bailey when he finds a potent foil, and the two clearly revel in the intertwined, parallel arcs that develop. Particularly over the course of the first piece, they take their time, probing, prodding, letting their respective lines course, ring against each other, unhurriedly unwind, only to lunge forth, bristling with skirling vigor, ending with Takagi looping a lyrical thread to close things out.

“Duo II” starts with a deliberate, spare solo by Bailey as his overtones and prickly lines splinter and scrabble with resolute deliberation. Takagi only enters two thirds of the way through, picking and prodding against Bailey’s lines, and then quickly gathering momentum as the two accelerate their way toward a skittering conclusion. The 8-minute long “Duo III” introduces a freely abstract lyricism to their playing, as the two navigate their way with restless flutters and flourishes, ending with a short solo segment for the reed player’s circuitous phrases. “Duo IV” picks up with pinched, overblown reed overtones that resolve into melodic threads which stretch over Bailey’s steely resonance and fissured harmonic fragments. Bailey’s mastery of attack and sustain shines through, often laid bare as Takagi drops back, waiting for opportune moments to dive back in. There are sections which build more density, owing perhaps to the rapport the two have developed over the set. But they never let that density overwhelm the proceedings, knowing when to pull back to build tension and then release in flurried torrents. This release is a welcome discovery of a prime, unknown session by Bailey and should serve to put Takagi on listeners’ radar.

–Michael Rosenstein

Dan Clucas + Jeb Bishop + Damon Smith + Matt Crane

Universal or Directional

Balance Point Acoustics 10010

Damon Smith

Whatever Is Not Stone Is Light

Balance Point Acoustics 10

Universal or Directional is a hard CD to find. Just black and white drawings, no words, on the front and back covers, though the spine does give the artists’ last names in tiny letters. Nevertheless, the album is a real beauty with some lovely music by Jeb Bishop, a favorite trombonist, and especially triumphant cornet music by Dan Clucas. He is so active and ingenious that he gives the whole album an optimistic feel. From little spits of sound in space to long atonal lines that twist about ever so freely, Clucas is the center of attention. Bishop likes to play longer tones while Clucas takes fanciful flights. The middle of “Foxing” is a near-monumental duet by those two horns and they’re both muted in their unaccompanied duet.

Universal or Directional is a hard CD to find. Just black and white drawings, no words, on the front and back covers, though the spine does give the artists’ last names in tiny letters. Nevertheless, the album is a real beauty with some lovely music by Jeb Bishop, a favorite trombonist, and especially triumphant cornet music by Dan Clucas. He is so active and ingenious that he gives the whole album an optimistic feel. From little spits of sound in space to long atonal lines that twist about ever so freely, Clucas is the center of attention. Bishop likes to play longer tones while Clucas takes fanciful flights. The middle of “Foxing” is a near-monumental duet by those two horns and they’re both muted in their unaccompanied duet.

Six of the CD’s nine improvisations are revealing duets. Bishop plays strong lyric lines as though he’s creating a whole composition, which contrasts with virtuoso bassist Damon Smith’s impetuosity in their duet: Bishop conceives in large designs, Smith in small ones. Another gem is Bishop in duet with Matt Crane’s deep, throbbing drums, from soft through central lines to long, low, final tones. A high point of the album is Clucas’s nervous improvisation in duet with Crane – great rapport, the drums become more dense as they progress. The three intriguing quartet improvisations touch on so many different feelings, the players are so different and such expressionists, most often complementing and occasionally ignoring each other that they seem to be meeting together for the very first time.

Damon Smith is a stunning bassist, a virtuoso of technique and imagination. Whatever Is Not Stone Is Light is a solo bass tour de force, an album of 17 cameos under two minutes long and six slightly longer improvisations. They’re fast, hyperactive pieces, mostly plucked or bowed in very low notes – often, so low that the notes almost all sound the same – and he loves to bow with the wood instead of the catgut. The longest track, “Kneading Trough,” is an excellent example of Smith’s purposefulness and mastery of elements of improvisation. An unusually expansive dynamic range, a close, fine sense of sound in space, a variety of sounds, a quick sense of contrasts, and dramatic accents are all aspects of a solo that evolves. The short pieces are concise atonal statements, sometimes witty, sometimes unbelievably quiet. For me, the CD is best heard a few tracks at a time. More and the Mariana Trench-deep sound and Smith’s brilliance become forbidding.

–John Litweiler

Jacques Coursil

The Hostipitality Suite

Savvy Records 001

Shortly before his passing earlier this year, Jacques Coursil finalized a record he’d been working on since 2018. Hostipitality Suite – the title is a conscious neologism – was released in June by Berlin-based arts “laboratory” Savvy Contemporary, for whom the project was first conceived. Originally collaborating with Marque Gilmore’s percussion and electronics in a live version that can be viewed on online platform Vimeo, this studio recording pairs Coursil’s trumpet with the synthesizers of his ubiquitous late-career collaborator Jeff Baillard. Best-known for his work in the New York avant-garde of the 1960s – recordings with Sunny Murray and Frank Wright and his own albums on BYG, the fascinating and complex Black Suite and Way Ahead – Coursil subsequently undertook a period of hiatus and introspection, with occasional undocumented performances, upon his return to France the following decade. When he re-emerged into the world of music, in part thanks to the encouragement of former student John Zorn, it was with the unique Minimal Brass, a record for multiple trumpets – all overdubbed by Coursil himself – which demonstrated his new control of the instrument, through circular breathing and other extended techniques. Rather than the brassy connotations of speed and volume that traditionally make up trumpet virtuosity, however, Coursil’s was a virtuosity of patience and ambiguity, one in which a softened articulation made the trumpet sound more like breath than shout. Subsequent releases, mainly using small ensembles, worked to address weighty historical concerns, from Clameurs, which reflected on Martinican identity via texts from Frantz Fanon and others, to Trail of Tears, which addressed the horrors of the Native American genocide and the Middle Passage. On these records, Coursil preferred to work in settings that suggested ambient music as much as jazz, often in collaboration with Baillard’s synth and keyboard settings. The results suggest something of the feel of better-known work by fellow trumpeters Jon Hassell and Nils Petter Molvaær, or the quieter side of the late Toshinori Kondo, but Coursil’s use of space and wispy melodicism are entirely his own: phrases that sound, paradoxically, like quiet fanfares, mournful lullabies sung to the self.

Shortly before his passing earlier this year, Jacques Coursil finalized a record he’d been working on since 2018. Hostipitality Suite – the title is a conscious neologism – was released in June by Berlin-based arts “laboratory” Savvy Contemporary, for whom the project was first conceived. Originally collaborating with Marque Gilmore’s percussion and electronics in a live version that can be viewed on online platform Vimeo, this studio recording pairs Coursil’s trumpet with the synthesizers of his ubiquitous late-career collaborator Jeff Baillard. Best-known for his work in the New York avant-garde of the 1960s – recordings with Sunny Murray and Frank Wright and his own albums on BYG, the fascinating and complex Black Suite and Way Ahead – Coursil subsequently undertook a period of hiatus and introspection, with occasional undocumented performances, upon his return to France the following decade. When he re-emerged into the world of music, in part thanks to the encouragement of former student John Zorn, it was with the unique Minimal Brass, a record for multiple trumpets – all overdubbed by Coursil himself – which demonstrated his new control of the instrument, through circular breathing and other extended techniques. Rather than the brassy connotations of speed and volume that traditionally make up trumpet virtuosity, however, Coursil’s was a virtuosity of patience and ambiguity, one in which a softened articulation made the trumpet sound more like breath than shout. Subsequent releases, mainly using small ensembles, worked to address weighty historical concerns, from Clameurs, which reflected on Martinican identity via texts from Frantz Fanon and others, to Trail of Tears, which addressed the horrors of the Native American genocide and the Middle Passage. On these records, Coursil preferred to work in settings that suggested ambient music as much as jazz, often in collaboration with Baillard’s synth and keyboard settings. The results suggest something of the feel of better-known work by fellow trumpeters Jon Hassell and Nils Petter Molvaær, or the quieter side of the late Toshinori Kondo, but Coursil’s use of space and wispy melodicism are entirely his own: phrases that sound, paradoxically, like quiet fanfares, mournful lullabies sung to the self.

On Hostipitality Suite, Baillard’s settings are sparser than on previous releases, avoiding rhythmically accented or groove-based settings for held notes that fade in and out almost as if they weren’t there at all. The use of space has more in common with Coursil’s duo with Alan Silva, Free Jazz Art, with the important added feature of texts spoken by Coursil himself. Coursil describes the piece both as a “a painting” and “a kind of lament”, “stretching time” around a short “libretto” – texts by Jacques Derrida, Emmanuel Levinas and Coursil’s long-time interlocuter, fellow Martinican Edouard Glisant, arranged into a kind of sparse poetry. Texts have been central to previous works – Coursil’s professional career from the 1970s on was, after all, for the most part in academic linguistics rather than music – but he doesn’t propose text as illustration of music or music as illustration of text. Neither does he collide the two in intermedial plenitude. Rather than imagining that any artform – any form of communication as such – can adequately capture the entirety of the historical burdens with which he’s concerned, Coursil’s music instead encourages us to think of the historical absences and gaps, the absence of adequate expression for that which is excluded from the Enlightenment narratives Western society tells itself.

Overdubbing speech and trumpet, alternating as if in dialogue or illustration, whilst also seeming to occupy separate or parallel spaces, this is a patient music that requires one to fully suspend expectations of development, progress or momentum so central to much of the jazz tradition. Suitably enough for a piece that concerns “margins” and “peripheries”, Coursil’s music is also comfortable with a kind of marginal or peripheral claim on attention, in which the listener might be asked – with the generosity extended to the stranger – to enter into a mood of contemplation in which attention may wander or focus into shards of emotional intensity. “Hospitalité, hostilité, hostipitalité” Coursil intones, riffing off a Derridean construct in which the plosive splitting apart of words and the movement from openness to closure assumes ever-greater significant at this time of pandemic, perpetual warfare, displacement, the closing of borders, and the increasingly murderous construct of “Fortress Europe.” “Entre toi et moi / la part d’ombre / opaque” (“Between you and me / the shadow part / opaque”) read the libretto’s final lines, from Glissant, and this music is doubly shadowed: the shadow of Coursil’s own earthly presence, now fallen silent; the shadows of racialised, continental exclusion, the legacies of imperialism’s past and continuing despoilation; the resonant gap between language and music, signifier and signified, breath and articulation that were Coursil’s ever-present concerns. A fitting farewell.

–David Grundy