Moment's Notice

Reviews of Recent Recordings

(continued)

The Nels Cline Singers

Macroscope

Mack Avenue MAC1085

As most folks reading this know, the polymath guitarist Nels Cline has slowed down his recording and touring with his own ensembles since joining alt-rock heroes Wilco nearly a decade ago. Few would begrudge Cline some much deserved cash and comfort, after his long decades of faithfulness to the Southern California avant-garde. And certainly for a player of such wide-ranging aesthetic interest, rock made a kind of sense (after all, he performed not just with Vinny Golia and Dennis Gonzalez but with Mike Watt and the Geraldine Fibbers). But that said, it’s nice to see the NCS back, since it was with this superbly empathic trio (in the company of bassist Trevor Dunn, replacing Devin Hoff, and percussionist Scott Amendola, with everybody playing electronics) that Cline most successfully brought together his multiple interests.

As most folks reading this know, the polymath guitarist Nels Cline has slowed down his recording and touring with his own ensembles since joining alt-rock heroes Wilco nearly a decade ago. Few would begrudge Cline some much deserved cash and comfort, after his long decades of faithfulness to the Southern California avant-garde. And certainly for a player of such wide-ranging aesthetic interest, rock made a kind of sense (after all, he performed not just with Vinny Golia and Dennis Gonzalez but with Mike Watt and the Geraldine Fibbers). But that said, it’s nice to see the NCS back, since it was with this superbly empathic trio (in the company of bassist Trevor Dunn, replacing Devin Hoff, and percussionist Scott Amendola, with everybody playing electronics) that Cline most successfully brought together his multiple interests.

Macroscope displays the genre-shuffling, attention to textural detail, love of grooves, and occasional unabashed lyricism that Cline’s music has always housed. Note how seamlessly the opening “Companion Piece” morphs from the kind of folkish strumming that Cline has loved since Quartet Music or Silencer to psych-improv shredding. Elsewhere, he uses the nice rimshot-driven groove on “Canales’ Cabeza” to set up a feature for his smart close harmony figures (and it’s always a pleasure to listen to this guy play so effortlessly and inventively). But there are changes too, and these I’m not always sold on. There’s certainly a spare texturalism to many of these pieces – like the blissed out, laid back “Red Before Orange,” with Yuka Honda’s electronics and Cyro Baptista’s percussion thickening the mix – that suggests he’s embraced something of Wilco’s economy in songcraft. This contrasts with the often overstuffed manic energy of Cline’s earlier records, though he remains often go-for-it aggressive in his soloing (and he’s always had a thing for the chordal jamming on display here anyways). What sometimes goes wrong is the way texture or detail sometimes gets in the way of compelling compositional or improvisational development.

On “Respira,” for example, there’s a perfectly pleasant shimmering quality to the music, but it inexplicably bogs down in thickets of percussion (Josh Jones and now-NCS member Baptista foment things) and Cline’s modest vocals. “Climb Down” is a kind of throwaway electro-groove, with guest Zeena Parkins on electronics and harp. Things are slightly better in terms of percussion and electronics on “The Wedding Band,” where Dunn plays some nicely burbling electric bass alongside Cline’s lap steel-sounding playing (his use of modest multi-tracking here is successful, as it generally is on the album), but the record turns then to spaced-out texture with lonesome acoustic lines (on the title track), the electric 12-string feature “Seven Zed Heaven” (whose trippy architecture is briefly given some edge courtesy of Dunn’s lovely grinding arco solo), the inconsequential blast “Sascha’s Book of Frogs,” or “Hairy Mother,” whose electro-noise sounds like some Butthole Surfers outtake with its mewling vocals buried in the squall. So while there are good moments here and there, too many of these pieces are loose space atmospheres with lots of effects strung together, leaving you wanting more narrative drama or improvisational urgency from such a capable group of musicians.

–Jason Bivins

Nigel Coombes + Steve Beresford

White String’s Attached

Emanem 5032

The pairing of violinist Nigel Coombes and multi-instrumentalist Steve Beresford was a fortuitous one, and while their work may not pop out in the pantheon of free duets, it’s damn impressive. Coombes and Beresford first recorded together in 1974 as part of the group Teatime (Incus 15, reissued on Emanem 5009), their work considered among the first of British free music’s “second wave.” With guitarist Roger Smith and drummer Terry Day, they worked as The Four Pullovers later in the 1970s, and after a lengthy absence reformed their duo in 1997 (Two To Tangle, Emanem 4017). White String’s Attached was initially released in 1980 on the Bead label, England’s home for younger free improvisers at their most unhinged (curiously, much of the catalog remains out of print), and presents Beresford and Coombes in a robust, tangled dance across three duets, all taped at London Musicians’ Collective concerts. The disc also includes a riveting and previously unreleased violin solo that would give Paul Zukofsky a run for his money. While these musicians may be noted more for their subversive tactics and diffuseness, the music here is built on energy and invention.

The pairing of violinist Nigel Coombes and multi-instrumentalist Steve Beresford was a fortuitous one, and while their work may not pop out in the pantheon of free duets, it’s damn impressive. Coombes and Beresford first recorded together in 1974 as part of the group Teatime (Incus 15, reissued on Emanem 5009), their work considered among the first of British free music’s “second wave.” With guitarist Roger Smith and drummer Terry Day, they worked as The Four Pullovers later in the 1970s, and after a lengthy absence reformed their duo in 1997 (Two To Tangle, Emanem 4017). White String’s Attached was initially released in 1980 on the Bead label, England’s home for younger free improvisers at their most unhinged (curiously, much of the catalog remains out of print), and presents Beresford and Coombes in a robust, tangled dance across three duets, all taped at London Musicians’ Collective concerts. The disc also includes a riveting and previously unreleased violin solo that would give Paul Zukofsky a run for his money. While these musicians may be noted more for their subversive tactics and diffuseness, the music here is built on energy and invention.

The bulk of their tango is rooted in the violin-piano chamber tradition, though Beresford does bring his bag of noisemakers to the proceedings for a few stretches. It’s actually somewhat rare to hear unfettered pianism in Beresford’s arsenal; his approach certainly echoes Misha Mengelberg in its poised playfulness, though perhaps less Monkish. Amid surprisingly dense runs there are snatches of whorled gospel and township majesty that quickly elide into parlor grace, not quite subsumed beneath Coombes’ bony scrabble. Though the means of recording seem minimal and lo-fi (as with a number of Bead releases), Beresford’s explosive invention and the sub-tonal detail of Coombes’ finger-work are never lost – in fact, the documentary cassette recording enhances the raw surge and wry telepathy of this music. And while the notes suggest an upending of staid classicism, White String’s Attached is bluesy in its devilishness, a program caught between folksy communication and volcanic gesture with passing glances at Romantic volume and 20th century art song. In a maddening, sweaty dance, Coombes and Beresford lock arms with humor, grace and weight, and created an extraordinary record in the process.

–Clifford Allen

Jacques Coursil and Alan Silva

FreeJazzArt: Sessions for Bill Dixon

RogueArt CD 0052

Trumpeter, composer, visual artist and professor Bill Dixon died nearly four years ago, on June 16, 2010 at the age of 84. In the last part of his life, as well as shortly after he left the earthly plane, the question of legacy was circulating heavily. It’s not always easy to say what someone’s legacy is, especially when the area in which that person worked was so broad, and Dixon is no exception. From a purely technical perspective he explored areas that few others thought to investigate on the trumpet. Whether sculpting subtonal chuffs or screams that felt like he was “trying to blow the bell off the horn,” Dixon’s palette remained connected to forebears like Miles, Dizzy, Ruby Braff and Tony Fruscella. In this sense, pushing the boundaries of an instrument (or a form of music) did not come at the expense of knowing where one came from. A committed and centered individual who eschewed prevailing tides (which exist even in the avant-garde), his value system extended beyond musical invention, while certainly informing a distinct body of work.

Trumpeter, composer, visual artist and professor Bill Dixon died nearly four years ago, on June 16, 2010 at the age of 84. In the last part of his life, as well as shortly after he left the earthly plane, the question of legacy was circulating heavily. It’s not always easy to say what someone’s legacy is, especially when the area in which that person worked was so broad, and Dixon is no exception. From a purely technical perspective he explored areas that few others thought to investigate on the trumpet. Whether sculpting subtonal chuffs or screams that felt like he was “trying to blow the bell off the horn,” Dixon’s palette remained connected to forebears like Miles, Dizzy, Ruby Braff and Tony Fruscella. In this sense, pushing the boundaries of an instrument (or a form of music) did not come at the expense of knowing where one came from. A committed and centered individual who eschewed prevailing tides (which exist even in the avant-garde), his value system extended beyond musical invention, while certainly informing a distinct body of work.

FreeJazzArt: Sessions for Bill Dixon is a series of suites composed by Martinique-born trumpeter Jacques Coursil and featuring him in duet with bassist Alan Silva. Coursil studied with Dixon in the mid-1960s and appeared in the trumpeter’s pieces for the Orchestra of the University of the Streets, as well as in collaborations with dancer-choreographer Judith Dunn including “Papers,” “File Box Piece,” and “Nightfall Pieces” (all 1968). The trumpeter relocated to Paris as part of a wave of musicians from New York, eventually waxing two LPs in the BYG Actuel series (Way Ahead, featuring an interpretation of “Papers” for quartet, and The Black Suite) before leaving music for a professorship in linguistics. He began recording again in 2005, though apparently he’d been refining his trumpet practice continually over the years. While always economical, his approach is much more pointillist now, compressed runs using a very narrow range of notes forming the music’s cells, occasionally splaying out into breathy vistas that reflect back on the themes’ taut density.

Silva’s history with Dixon is perhaps longer – they performed hours of duo music in the mid-60s, sometimes augmented by Dunn’s movement. Apparently they were slated to tour England in 1966 but the UK musicians’ reciprocity law scuttled the project. Unfortunately no recordings from this early period survive, though their duo was the bedrock for quartets and a sextet, represented by recordings for Soul Note in 1980 and 1981. While Silva may have been someone “unable to play the same thing twice” (according to Dixon), his explosive unpredictability has been reigned in over the last fifty years. He’s still a rugged counterpart to Coursil’s buoyant arrows, deftly tugging and sawing a range of soft underlines and painterly asides.

Both Dixon and Coursil centered much of their music around the bass (Béb Guerin was the bassist of choice on Way Ahead and The Black Suite), though musicians who have picked up the mantle in recent years haven’t necessarily mined this area (should they?). For two players who knew this fascination well, and were in fact directly linked to it, FreeJazzArt is an appropriate homage, though as one would hope the music diverges from anything possible in the preceding decades. In terms of tone, Coursil does have a fair amount of Dixon in him, at least in the brushier passages, but there is a different sort of clarion-ness as his piercing, ochre centrality is that of a unique voice. The way in which a limited range of colors can be used to create something with this vastness and magnificence is a teaching not frequently adhered to, and the world created here is both pared-down and microcosmic. Certainly in part the sculpture is Dixonian, but in building its own concentrated environment, this music is a distinctly powerful piece of art for which the concept of a “tribute” is inexact. In creating something highly individual, a tough legacy is receiving proper due.

–Clifford Allen

George Davis

Scapula: Bop Acetates / Chicago, 1949

Corbett vs. Dempsey 14

Here’s a 27-minute oddity, ripped from an acetate recording that sounds as if George Davis was auditioning for prospective sponsors or for a radio station in hopes of broadcasting his band. The sound quality isn’t quite as bad as old Boris Rose bootleg LPs, but it’s not good either. Jump Town was a southwest-side Chicago club that lasted around six years and was noted for at least two things: 1) soon after the Billy Eckstine band broke up, a Gene Ammons-led band with ex-Eckstiners Sonny Stitt and Miles Davis played there; and 2) it was where a teen-aged Jackie Cain sat in with the George Davis group, which included pianist Roy Kral, her future singing partner and husband. Cain sings on Davis’s only recording (1947), a two-sided 78 on the Chess brother’s early Aristocrat label. And that’s all we now know for sure about George Davis.

Here’s a 27-minute oddity, ripped from an acetate recording that sounds as if George Davis was auditioning for prospective sponsors or for a radio station in hopes of broadcasting his band. The sound quality isn’t quite as bad as old Boris Rose bootleg LPs, but it’s not good either. Jump Town was a southwest-side Chicago club that lasted around six years and was noted for at least two things: 1) soon after the Billy Eckstine band broke up, a Gene Ammons-led band with ex-Eckstiners Sonny Stitt and Miles Davis played there; and 2) it was where a teen-aged Jackie Cain sat in with the George Davis group, which included pianist Roy Kral, her future singing partner and husband. Cain sings on Davis’s only recording (1947), a two-sided 78 on the Chess brother’s early Aristocrat label. And that’s all we now know for sure about George Davis.

Judging from this CD Davis was a JATP-like tenor saxist given to unimaginative jump-band/R & B riffing, one-note riding, and screaming freak tones. He also could play decent bop on the tenor, as in his solo on the title song (he announces it “skap-OO-la”), before he blasts a chorus of induced hysteria. On alto sax he plays rather like Camarillo-style Charlie Parker and even on this crummy recording you can hear he had a big, strong sound. That alto sound in his ballad “Body and Soul” is so lovely that I can see how he might have played lead alto in two of Chicago’s best early-1950s big bands, as one of my informants maintained. Yeah, Davis was sending mixed messages, but a musician has to keep working.

Here are three familiar songs and six originals (but “Piano Man’s Idea” resembles a slowed-down Fats Navarro song, “Going to Minton’s”). Mostly it’s Davis soloing. A trumpeter with Gillespie-like brashness and a bop guitarist get little solos, mostly a strain or two, and a pianist with an attractive, Dodo Marmarosa-like flow of feeling offers choruses on most pieces. Who are these unidentified guys? Each of them is more together than Davis.

–John Litweiler

Digital Primitives

Lipsomuch/Soul Searchin’

Hopscotch CD Hop 51

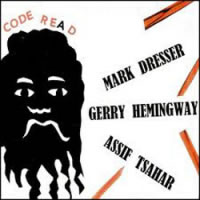

Assif Tsahar + Gerry Hemingway + Mark Dresser

Code Re(a)d

Hopscotch CD Hop 48

Tenor saxophonist and bass clarinetist Assif Tsahar was, in the late ‘90s and early ‘00s, a formidable fixture on the New York free music scene, working regularly with bassist William Parker, multi-instrumentalist Cooper-Moore, drummer Rashied Ali and other five-borough luminaries. Much of Tsahar’s output has been on his Hopscotch label, which has also released recordings by Matthew Shipp, Yoni Kretzmer, and Agustí Fernandez. While he returned to his native Israel over a decade ago, Tsahar remains inextricably tied to the fabric of New York improvisation. Perhaps it is because his sound, rooted in Sonny Rollins, Archie Shepp and Frank Lowe, is so quintessentially urbane and imbued with both frantic steeliness and boiling control.

Tenor saxophonist and bass clarinetist Assif Tsahar was, in the late ‘90s and early ‘00s, a formidable fixture on the New York free music scene, working regularly with bassist William Parker, multi-instrumentalist Cooper-Moore, drummer Rashied Ali and other five-borough luminaries. Much of Tsahar’s output has been on his Hopscotch label, which has also released recordings by Matthew Shipp, Yoni Kretzmer, and Agustí Fernandez. While he returned to his native Israel over a decade ago, Tsahar remains inextricably tied to the fabric of New York improvisation. Perhaps it is because his sound, rooted in Sonny Rollins, Archie Shepp and Frank Lowe, is so quintessentially urbane and imbued with both frantic steeliness and boiling control.

Cooper-Moore and Tsahar have a long history together, and their work remains vital, whether in duo or with Digital Primitives, a trio featuring drummer Chad Taylor. Lipsomuch/Soul Searchin’ is a double album of nineteen improvisational frameworks drawing from Piedmont funk, free music and informal blues, for which the center is Cooper-Moore’s quiver of homemade instruments: diddly-bo (a bass monochord), twanger/fretless banjo and mouth bow. Percussive and throaty, Cooper-Moore’s diddley-bo is often the heartbeat, limned by Taylor’s dry, economical cracks, while Tsahar’s expressionist shouts and curlicues occupy the stratosphere (“Grassblare”), while the three coalesce into an ultra-limber stew a few beats later, on the title track to Soul Searchin’. Interestingly, it’s not too difficult to discern alternate recording methods across the sessions that make up the discs – some cuts riotously pop out of the speakers with jarring clarity, while others emit a gritty and mildly distant fog. Of course, the indistinct can have as much of an aesthetic effect as the distinct, as when Tsahar’s tenor is wrapped in wooly low fidelity with the rugged spaciousness of a Saturn recording. One piece is absent reeds, the gorgeous “Talking in Tongues” for cymbals, kalimba, and mouth bow. Cooper-Moore tells a story with a contact mike, wood and horsehair, declaiming and unfolding pathos-filled lines in an extraordinary series of passages.

Code Re(a)d features the trio of Tsahar, bassist Mark Dresser and drummer Gerry Hemingway on a program of eight group improvisations recorded live at Tel Aviv’s Levontin7. The Hemingway-Dresser rhythm team has been fine-tuned over decades of collaboration, creating a shared language into which Tsahar’s fluid vocabulary fits well. Dresser’s amplified upper-register plucks and stomach-pitted lows do focus the improvisations, but Hemingway’s subtle relentlessness pushes the trio forward, approaching an oddly lopsided swing on “Deceptive Responses.” Here Tsahar shimmies and digs in his heels before the three segue into breathy, whining harmonics and a dusky plod on “Expanded Metaphors,” where the tenorist moves from pillowy underscores to muscular existential shouts, supported by distant martial progress. The trio is at its scrappiest on tempo/blowing numbers, where Hemingway and Dresser get into a clattering bounce around the reedist’s bright, florid runs and bluesy declamations. It’s also interesting to hear Tsahar’s burbling athletics in sections of exploratory drift, though with Hemingway at the helm, such passages retain rhythmic detail, as on “(A)pplied Syntax.” Code Re(a)d is a strong collective statement formed of new blood and longtime partnerships, and Tsahar has never sounded better than he does in 2014.

–Clifford Allen