Moment's Notice

Recent CDs Briefly Reviewed

(continued)

Sunny Murray

Big Chief

Eremite mte-51 (LP)

Solidarity Unit, Inc.

Red, Black, and Green

Eremite mte-52 (LP)

If anyone might question the commitment of Michael Ehlers and Eremite to the spirit and letter of the free jazz tradition, these two LPs stand as testimony in his favor. When they first arrived in the mail I had the impression of a package that had been lost in the mail for forty years, weighty vinyl LPs in bright mint sleeves.

If anyone might question the commitment of Michael Ehlers and Eremite to the spirit and letter of the free jazz tradition, these two LPs stand as testimony in his favor. When they first arrived in the mail I had the impression of a package that had been lost in the mail for forty years, weighty vinyl LPs in bright mint sleeves.

Sunny Murray’s Big Chief was recorded in Paris in 1969, then a crucible for expatriate American free jazz musicians. Murray has demonstrated his compositional skills on few records, but he has an authentic and radical voice as a composer, though with clear affinities for associates like Don Cherry and Albert Ayler. I can recall hearing him lead an octet in 1966 in which predetermined materials had been reduced to a sustained, high-pitched trill. Here he achieves striking coherence and intensity with an octet made that includes Americans, French and South Africans, including saxophonists Ronnie Beer and Kenneth Terroade who lend an appropriately Ayler-ish cast—vast swaying vibratos—to the ensembles. Murray’s band concept is very much an ensemble one, and his own cymbals impart a constant shimmer to the sound that’s reflected in the continuous strings, with Beb Guerin on bass and Alan Silva on violin and viola. That rich texture both exalts and subsumes the individuals, so that it’s the sheer sound of the band that you remember, whether jerkily making their way through the angular “Hilarious Paris,” driving on poet Hart Leroy Bibb on his “Straight Ahead,” or playing Murray’s arrangement of Richard Rodgers’ “This Nearly was Mine,” a wailing, hymn-like recitation that takes on the mood of a lyrical crucifixion.

The Solidarity Unit, Inc. is also a large-ish band led by a drummer – Charles “Bobo” Shaw – but it’s very different in character, often feeling like a raw jam. It’s also a live recording from the St Louis BAG performance space, and it has the dense mass of amateur recording in the period. Recorded on the day of Jimi Hendrix’s death and dedicated to his memory, the music has an incendiary power, always alert and driving, but with sudden explosive entries by the two trumpets that suggest the drama and power of R ‘n’ B. While many of the instruments blur into a collective roar, there are some very fine moments from Oliver Lake, already playing with a controlled frenzy, and Joseph Bowie, whose trombone possesses a fluid bluster. There’s also a rare appearance by a very intense Richard Martin, one of the first guitarists to begin assembling a personal vocabulary from free jazz and rock. The concluding moments of the side-long “Beyond the New Horizon” present a lyrical postlude to the heat, with just Lake and Shaw on flute and drums.

There’s something quite wonderful about these two LPs, reproduced in exacting detail from their original issues but with the added quality of 180-gram vinyl. While the Solidarity Unit is very good, the Murray is great.

–Stuart Broomer

Arvo Pärt

In Principio

ECM New Series 2050

In addition to 2009 being ECM’s 40th anniversary, the label’s New Series celebrates its silver. Even though its 260 titles include dozens of recordings of early music and works by 18th and 19th Century composers, the New Series has appreciably moved the center point of newness in classical music. This is in no small measure due to the Series’ championing of Arvo Pärt, whose Tabula Rasa was its inaugural release. Subsequently, In Principio has particular resonance; the epistemological blank slate referenced by the earlier work is now filled in with the creation narrative that opens the Gospel of John on "In Principio," a five-part composition for mixed chorus and orchestra. It is a work that will reinforce the Estonian composer's renown for creating a hallowed ambiance with bold formal propositions. The bookend-like first and final movements entwine recitative-like parts for the chorus and staccato motives for strings and brass that build in intensity at the beginning of the piece and unwind ponderously to silence at the end. In the middle sections, Pärt uses a wide assortment of devices – everything from crisp monody to harmonics-rich drones and the empathic repetition that is the cornerstone of Minimalism – but maintains a taut emotional continuity as the piece completes its arc. Throughout "In Principio" and the five other pieces in the collection, conductor Tõnu Kaljuste's proximity to Pärt – this is the fifth composer-present recording for the New Series alone – is evident in the extremes of blaring brass and ethereal strings as well as the synthesis of the ancient and the modern that is part and parcel of Pärt’s writing. To these ends, the performances of the Estonian National Symphony Orchestra, the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir and the Tallinn Chamber Orchestra cannot be underestimated, nor can Manfred Eicher’s hand in sequencing the material. After the title piece, the somber “La Sindone” for orchestra, and two other works for chorus and orchestra drawing upon Pärt’s affinity for liturgical and Gregorian literature, the two short works for smaller ensembles end the album with a leaner sound that suits his music well. “Mein Weg” for 14 strings and percussion has an airier feel and places his layered string figures in starker relief, while “Für Lennart in Memoriam” for strings, commissioned by the late Estonian president Lennart Meri for his own burial, ends the album with unadorned sighs and whispers.

In addition to 2009 being ECM’s 40th anniversary, the label’s New Series celebrates its silver. Even though its 260 titles include dozens of recordings of early music and works by 18th and 19th Century composers, the New Series has appreciably moved the center point of newness in classical music. This is in no small measure due to the Series’ championing of Arvo Pärt, whose Tabula Rasa was its inaugural release. Subsequently, In Principio has particular resonance; the epistemological blank slate referenced by the earlier work is now filled in with the creation narrative that opens the Gospel of John on "In Principio," a five-part composition for mixed chorus and orchestra. It is a work that will reinforce the Estonian composer's renown for creating a hallowed ambiance with bold formal propositions. The bookend-like first and final movements entwine recitative-like parts for the chorus and staccato motives for strings and brass that build in intensity at the beginning of the piece and unwind ponderously to silence at the end. In the middle sections, Pärt uses a wide assortment of devices – everything from crisp monody to harmonics-rich drones and the empathic repetition that is the cornerstone of Minimalism – but maintains a taut emotional continuity as the piece completes its arc. Throughout "In Principio" and the five other pieces in the collection, conductor Tõnu Kaljuste's proximity to Pärt – this is the fifth composer-present recording for the New Series alone – is evident in the extremes of blaring brass and ethereal strings as well as the synthesis of the ancient and the modern that is part and parcel of Pärt’s writing. To these ends, the performances of the Estonian National Symphony Orchestra, the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir and the Tallinn Chamber Orchestra cannot be underestimated, nor can Manfred Eicher’s hand in sequencing the material. After the title piece, the somber “La Sindone” for orchestra, and two other works for chorus and orchestra drawing upon Pärt’s affinity for liturgical and Gregorian literature, the two short works for smaller ensembles end the album with a leaner sound that suits his music well. “Mein Weg” for 14 strings and percussion has an airier feel and places his layered string figures in starker relief, while “Für Lennart in Memoriam” for strings, commissioned by the late Estonian president Lennart Meri for his own burial, ends the album with unadorned sighs and whispers.

–Bill Shoemaker

Alfred Schnittke/Alexander Raskatov

Symphony No. 9/Nunc Dimittis

ECM New Series 2025

The most acclaimed Russian composer of the generations following Dmitri Shostakovich, Schnittke initially made his mark in the 1970s with scores that incorporated musical quotations, parodies, collages, and a distorted use of tradition in a “polystylistic” montage that viewed contemporary composition from an ironic, absurdist perspective. But by 1985, when he suffered the first of his life-threatening strokes, Schnittke’s music began to exhibit ever more somber, pessimistic, melancholy qualities. Comparisons with the career of Shostakovich – which, similarly, began with rebellious, satiric scores and concluded with a series of death-obsessed last works – didn’t hurt Schnittke’s reputation, and despite three increasingly debilitating strokes in the early ‘90s, he remained a prolific and occasionally profound composer in the same dramatically expressionist vein, with a few personal quirks, that Shostakovich inherited from Gustav Mahler. On his death in 1998, Schnittke left behind the manuscript of a completed Ninth Symphony, which had been painstakingly and awkwardly notated with his left hand after his right side had been paralyzed. His widow, Irina, eventually gave the score to the young composer and friend of Schnittke’s, Alexander Raskatov, to be prepared for performance by the Dresden Philharmonic under Dennis Russell Davies, who do the honors here.

The most acclaimed Russian composer of the generations following Dmitri Shostakovich, Schnittke initially made his mark in the 1970s with scores that incorporated musical quotations, parodies, collages, and a distorted use of tradition in a “polystylistic” montage that viewed contemporary composition from an ironic, absurdist perspective. But by 1985, when he suffered the first of his life-threatening strokes, Schnittke’s music began to exhibit ever more somber, pessimistic, melancholy qualities. Comparisons with the career of Shostakovich – which, similarly, began with rebellious, satiric scores and concluded with a series of death-obsessed last works – didn’t hurt Schnittke’s reputation, and despite three increasingly debilitating strokes in the early ‘90s, he remained a prolific and occasionally profound composer in the same dramatically expressionist vein, with a few personal quirks, that Shostakovich inherited from Gustav Mahler. On his death in 1998, Schnittke left behind the manuscript of a completed Ninth Symphony, which had been painstakingly and awkwardly notated with his left hand after his right side had been paralyzed. His widow, Irina, eventually gave the score to the young composer and friend of Schnittke’s, Alexander Raskatov, to be prepared for performance by the Dresden Philharmonic under Dennis Russell Davies, who do the honors here.

Mahler, even more than Shostakovich, haunts this final symphony, with echoes from his own Ninth and unfinished Tenth symphonies, and the song cycle Das Lied von der Erde – an oboe phrase here, a furtive waltz there, a funereal bass drum, the contrast of subterranean brass and clarinet with an arcing, poignant melody in the strings. The extended first movement outlines an arduous journey, repeatedly building to vague, unsatisfying peaks and receding to moments of private despair. In the remaining two shorter movements, Schnittke exerts more effort, though without exaggerated emphasis, increasing the pace but blanketing the flow of details with an Ivesian fog of simultaneously aligned or juxtaposed fragments and events, reconfirming the polystylistic methods which, perhaps with tongue-in-cheek, he once described as “sleepwalking.” Though there is a lack of singular themes throughout the work, this sleepwalking – the semi-conscious movement, or perhaps partial or obscured sense of awareness, through a life – gives the music an impulsive atmosphere and symbolic breadth that make it a more engaging memento mori than his morose Eighth Symphony.

Working so intimately with the score, Raskatov was inspired to compose an addendum to the symphony – and to his credit, his Nunc Dimittis (“Lord, now dost thou let thy servant depart”), a setting of poems by Joseph Brodsky and Starets Siluan, confronts the specter of death from a different musical point-of-view. The soloist (Elena Vassilieva) and chorus (The Hilliard Ensemble) alternate between extensions of traditional chant and the type of extreme vocalism devised by Gyorgy Ligeti in his famous Requiem, though the conclusion is also reminiscent of the death scene from Mussorgsky’s opera Boris Godunov, all contained in an orchestral environment of bell-like motifs and dissonant drones, with an undisguised funeral march as frequent counterpoint. Whatever its inspiration, Raskatov’s piece has its own character and drama, and deserves a life of its own.

–Art Lange

Wadada Leo Smith

Procession of the Great Ancestry

Nessa ncd-26

Two tracks on this 1983 Chicago session – the opener, “Blues: Jah Jah is the Perfect Love” and “Who Killed David Walker?,” embedded deeper in the album – tend to place Procession of the Great Ancestry on a sideways dotted line on the flow chart of Wadada Leo Smith’s discography. Featuring the trumpeter’s vocals, Louis Myers’ electric guitar, and the two-bass hit of Joe Fonda’s electric instrument and Mchaka Uba's double bass, these blues-infused pieces draw upon Smith’s early exposure to Delta blues and work in R&B bands. However, Myers’ clean sound, Bobby Naughton's vibes and Kahil El’ Zabar’s hand drumming on "Blues" give the music a distinct African feel. The remaining five pieces are very much in the vein of Smith’s Rhythm Unit compositions of that period, fitting hand in glove with his compositions on another ’83 recording, Rastafari (a collaboration with the Bill Smith Ensemble, it was first issued on Sackville and now available as a Boxholder CD). Significantly, the Toronto date also featured a vibraharpist, an indication of how central New Dalta Ahkri stalwart Naughton was to Smith’s conceptions. Naughton’s understanding of Rhythm Units as an activator of interaction – rather than a measurement – is particularly well conveyed on longer performances like the title tune, “The Third World, Grainery of Pure Earth” and “Celestial Sparks in the Sanctuary of Redemption,” where he, Fonda (playing double bass) and El’ Zabar (who shuttles between traps and miscellaneous percussion) dovetail Smith and each other one moment, and then pull strenuously on the music the next. This is music that largely moves in fits and starts, one whose generative principles are hard if not impossible to pin down at any moment, yet there is an ear-grabbing, organic feel to it. Much of this is traceable to Smith, a magnetic presence even whether he is squeezing out muted long notes, stretching textures or generating riveting runs in the album's more abstract moments. He is awe-inspiring playing a humble, mournful unison theme with tenor saxophonist John Powell on "Nuru Light: The Prince of Peace;" utilizing a taped excerpt from Martin Luther King, Jr.'s last speech, this short piece is among the most profound statements Smith has ever recorded.

Two tracks on this 1983 Chicago session – the opener, “Blues: Jah Jah is the Perfect Love” and “Who Killed David Walker?,” embedded deeper in the album – tend to place Procession of the Great Ancestry on a sideways dotted line on the flow chart of Wadada Leo Smith’s discography. Featuring the trumpeter’s vocals, Louis Myers’ electric guitar, and the two-bass hit of Joe Fonda’s electric instrument and Mchaka Uba's double bass, these blues-infused pieces draw upon Smith’s early exposure to Delta blues and work in R&B bands. However, Myers’ clean sound, Bobby Naughton's vibes and Kahil El’ Zabar’s hand drumming on "Blues" give the music a distinct African feel. The remaining five pieces are very much in the vein of Smith’s Rhythm Unit compositions of that period, fitting hand in glove with his compositions on another ’83 recording, Rastafari (a collaboration with the Bill Smith Ensemble, it was first issued on Sackville and now available as a Boxholder CD). Significantly, the Toronto date also featured a vibraharpist, an indication of how central New Dalta Ahkri stalwart Naughton was to Smith’s conceptions. Naughton’s understanding of Rhythm Units as an activator of interaction – rather than a measurement – is particularly well conveyed on longer performances like the title tune, “The Third World, Grainery of Pure Earth” and “Celestial Sparks in the Sanctuary of Redemption,” where he, Fonda (playing double bass) and El’ Zabar (who shuttles between traps and miscellaneous percussion) dovetail Smith and each other one moment, and then pull strenuously on the music the next. This is music that largely moves in fits and starts, one whose generative principles are hard if not impossible to pin down at any moment, yet there is an ear-grabbing, organic feel to it. Much of this is traceable to Smith, a magnetic presence even whether he is squeezing out muted long notes, stretching textures or generating riveting runs in the album's more abstract moments. He is awe-inspiring playing a humble, mournful unison theme with tenor saxophonist John Powell on "Nuru Light: The Prince of Peace;" utilizing a taped excerpt from Martin Luther King, Jr.'s last speech, this short piece is among the most profound statements Smith has ever recorded.

–Bill Shoemaker

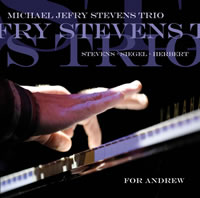

Michael Jefry Stevens

For Andrew

Konnex KCD 5112

If Michael Jefry Stevens seldom registers as of significant magnitude in anyone’s casual star-catalogue of jazz piano (there is, admittedly, a background in rock to live down), that’s largely and perversely because of his now career-long tendency to present himself as a member of named bands and overlapping collectives. The jointly named group with bassist Joe Fonda is perhaps the best known, but the pianist has also been a member of Conference Call, the Mosaic Sextet, and, way back, Liquid Time. A recurring cast of collaborators has included trumpeter Herb Robertson, saxophonist Mark Whitecage, drummers Harvey Sorgen and Jeff Siegel, and others, including violinist Mark Feldman and guitarist Dom Minasi. This isn’t necessarily one of the more prominent constellations in contemporary jazz/improvisation, but – even going no further than those names – one of the most interesting.

If Michael Jefry Stevens seldom registers as of significant magnitude in anyone’s casual star-catalogue of jazz piano (there is, admittedly, a background in rock to live down), that’s largely and perversely because of his now career-long tendency to present himself as a member of named bands and overlapping collectives. The jointly named group with bassist Joe Fonda is perhaps the best known, but the pianist has also been a member of Conference Call, the Mosaic Sextet, and, way back, Liquid Time. A recurring cast of collaborators has included trumpeter Herb Robertson, saxophonist Mark Whitecage, drummers Harvey Sorgen and Jeff Siegel, and others, including violinist Mark Feldman and guitarist Dom Minasi. This isn’t necessarily one of the more prominent constellations in contemporary jazz/improvisation, but – even going no further than those names – one of the most interesting.

More unusual instrumentations aside, trio playing has been central to Stevens’ activity. There was the group with Sorgen and Steve Rust, and another, apparently concurrent, with Siegel and Tim Ferguson. “Siege” is involved here, alongside the huge-voiced Peter Herbert on bass, and it’s immediately clear how important to Stevens’ approach is a strong bass/drums axis. Herbert is strongly featured on the majority of tracks and the kit is always forward in the mix, allowing every small detail to come across with definition. Stevens met Siegel at an Andrew Hill concert, and though Andrew was still alive when this set was recorded in spring 1996 – why do so many terrific albums languish on the shelves for so long? – and despite the absence of any Hill themes or obvious allusions in the music, it’s now presented as a kind of memorial.

It actually opens with more of a Bill Evans/McCoy Tyner flourish, a weighty, downward flurry of sound on “Nardis” that is closer in impact to the intro of “After the Rain.” The Davis/Evans theme is one of just two non-originals on the record, the other being “Lazy Afternoon,” which receives an extended reading, almost enervated in places, sometimes bordering on sinister. The word’s chosen advisedly, because Stevens often seems to lack much of a “left hand,” leaving the bottom-end stuff to Herbert. That’s a false impression. The chording is often very spare, compared to the fast trills and arpeggios that remain Stevens’s most obvious stylistic signature, but it’s absolutely of the essence. One picks it up in “Spirit Song” and on “Parallel Lines,” the disc’s most substantial performance. Frankly, that’s what I’d have called the record, except the lines are never quite equidistant, but take a quietly playful delight in seeming to lose the plot; there are moments here where you might wonder if the trio isn’t working off the same chart at all; then it all comes together, without histrionic cadences, but with impeccable logic.

“Waltz” and “Lazy Waltz” aren’t obviously related, though the latter may well derive something from run-throughs of ‘”Lazy Afternoon.” In the same way, “The Lockout” might be an inversion of certain components of “Parallel Lines.” Or, it may simply be that the overall approach and group sound is so consistent that one intuits connections that aren’t there at any conscious level on the composer’s or players’ part.

Chronologically, these performances date back to around the same time as Elements, his 1996 group record with Whitecage, Minasi and Dominic Duval. To that extent, it’s already part of Stevens’ musical past, though very different and more outwardly conventional than the Leo record’s fairly abstract and schematic approach to earth, air, fire and water. On that analogy, you might say that For Andrew is more concerned with earth and air than with the others. That’s not to say it lacks fire or risks dryness.

–Brian Morton