Moment's Notice

Reviews of Recent Media

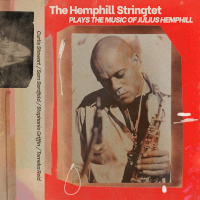

The Hemphill Stringtet

The Hemphill Stringtet Plays the Music of Julius Hemphill

Out of Your Head OOYH035

It is now fully 30 years since Julius Hemphill died. His stature as a composer and instrumentalist has since grown. It is somewhat surprising that his music has been infrequently performed by others outside the posthumous editions of his Sextet, given a discography studded with essential albums like Dogon A.D., his Nonesuch big band date, and the Sextet’s fat man and the hard blues – not to mention the slew of compositions like “Steppin’” and “R&B” and arrangements of “Take the ‘A’ Train” and “Let’s Get It On” he penned for World Saxophone Quartet. And it’s sad that ambitious projects like Long Tongues: A Saxophone Opera and orchestral works like “Plan B” remain dormant, works that would give a much fuller picture of Hemphill’s scope and depth.

What’s remarkable about Hemphill’s recorded output is that it spans less than 25 years, and that he only began to receive commissions for concert music in the last decade of his life, when he was already in declining health. Had he lived another decade – he recently turned 57 when he passed – the times may well have caught up to him; in addition to his greying eminence in the jazz world, he would have undoubtedly benefited from concert music organizations and ensembles broadening their programming in their search of relevance. By then, he may have been regarded as a composer without modifiers like jazz and African American affixed with the krazy glue of cultural bias.

Fortunately, the stewarding of Hemphill’s legacy is in the most capable hands of Marty Ehrlich, the composer and instrumentalist who was a teenager when he met Hemphill during the heyday of St. Louis’ Black Artists Group. Ehrlich began performing with Hemphill in the late 1970s in various larger scale projects after they both relocated to New York, and became the musical director for the Sextet in 1996. He was therefore the best choice to be the chief researcher of Hemphill’s papers, a vast trove of scores, recordings, and other documents housed at New York University.

Ehrlich produced two prior essential collections of Hemphill’s music: One Atmosphere (Tzadik) and the 7-disc The Boyé Multi-National Crusade for Harmony (New World). Both collections include chamber works that would have prompted reassessments of Hemphill’s art had they been issued in his lifetime. For starters, “One Atmosphere,” a piano quintet, and the box set’s “Parchment” for solo piano, feature pianist Ursula Oppens, Hemphill’s late-life partner; while poignance and reflection were regular features of Hemphill’s music, his connection with the internationally renowned Oppens, prompted especially deep dives on these compositions.

The Boyé Multi-National Crusade for Harmony also included the Daedalus String Quartet’s take on “Mingus Gold,” a tryptic comprised of “Nostalgia in Times Square,” “Alice in Wonderland,” and “Better Get Hit in Your Soul,” commissioned and premiered by Kronos Quartet during their mid-1980s infatuation with arrangements of jazz classics. It remains baffling that the globe-trotting quartet passed on recording “Mingus Gold,” as it checked all the boxes for inclusion on one of their many ballyhooed Nonesuch albums. Hemphill would have significantly benefited if they had.

Ehrlich also undertook the formidable task of publishing Hemphill’s music for saxophone quartet and sextet. “Body of work” is frequently applied to material that barely amounts to a limb; but, Hemphill’s music for saxophone ensembles more than qualifies. And, as it turns out, they are works easily adapted for string quartets.

Curtis Stewart, Sam Barfeld, Stephanie Griffin + Tomeka Reid © 2025 Robert Sumberg-O'Haire

First assembled to play “Mingus Gold” at Chicago’s Frequency Festival in 2022, The Hemphill Stringtet has melded aspects of Hemphill’s music for chamber groups and saxophone ensembles together in an album that will cast new, needed light on the composer and establish a franchise capable of the long haul. Violinists Curtis Stewart and Sam Barfeld, violist Stephanie Griffin, and cellist Tomeka Reid not only have the skill set to run in elite concert music circles, but they also have the ears of improvisers who understand the chemistry between vernaculars and abstraction that animate Hemphill’s music.

“Mingus Gold” is the presumptive centerpiece of The Hemphill Stringtet Plays the Music of Julius Hemphill, but it is arguably the least interesting piece on the album. Granted: it extends the three Mingus compositions to new realms with Hemphill’s blend of boldness and nuance. The scores are brimming with incandescent flares that reveal his sensitivity to Mingus’ protean sensibility. Ehrlich mentions in his notes to the New World box set that there are moments that sound like Mingus himself is improvising, an astute point that can be taken a step further in regards to the Hemphill Stringtet’s reading: there are passages that sound like Hemphill himself is improvising.

However, there is an unavoidable entropic aspect to “Mingus Gold,” in that Hemphill expounded on Mingus instead of creating a work from scratch, and that it is a product of a concert music establishment way late in recognizing composers of the moment and, in this case, relegating one of the most profoundly original to recast ingots of “classical jazz.” There is also the embedded irony that it was Mingus who fought so vigorously to be recognized as a composer, sans modifiers, and that this supposedly corrective commission had the presumably unintended consequence of thwarting comparable recognition of Hemphill at a critical point in his life. This said, “Mingus Gold” outshines the other endeavors in this vein from that period and deserves to be performed again and again.

Arguably, the real gems of the album are the four Hemphill compositions from the WSQ and Sextet books. The Stringtet made several brilliant decisions in this regard. There is no better vehicle to open the proceedings and establish Hemphill’s mastery of voicings and bar-to-bar emotional gradations than “Revue.” There is an initial optimism in the theme which, instead of blossoming into full sunshine, turns wistful and introspective, ultimately relieved by the baritone motive now employed by the cello. Reid proves to be a cohering anchor in the ensuing, largely improvised section, a sequence of solos by all hands that reveals a finely tuned ensemble identity.

The pairing of “My First Winter” and “Touchic” is equally inspired. The lyricism of the former evokes the fading warmth of embers with the encroachment of bleak midwinter without sentimentality, a precarious balance the Stringtet gracefully maintains. The latter is an incisive theme that the quartet vigorously saws. The pieces are deftly joined through a texture-rich improvisation that doesn’t reveal its function until the last possible instant. The resulting medley is a tour de force. “Choo Choo” is the only saxophone ensemble-based chart Hemphill did not record himself. Its initial chugging rhythms derail into fishtailing lines, only to get back on track before the brakes grind, closing the album with the quintessentially American image of the freedom train.

This is a recording that will elicit superlatives from the better jazz critics. But more important than the buzz attending The Hemphill Stringtet Plays the Music of Julius Hemphill – and hopefully more lasting – is the overdue justice it serves.

–Bill Shoemaker