Moment's Notice

Reviews of Recent Media

(continued)

Otherlands Trio

Star Mountain

Intakt CD442

The name of bassist Stephan Crump and drummer Eric McPherson’s latest joint venture straight away confirms its relationship to another of their outfits, the Borderlands Trio, and attains a similar level of cohesion. In taking on the role as the third member of the collective, alto saxophonist Darius Jones revels in a rapport every bit as intuitive as pianist Kris Davis, though the character is markedly dissimilar. This is a saxophone trio grounded in the tradition yet liberated from written charts, shaping sonic architecture on-the-fly from repeated cells, extemporized melodies, and mutable riffs.

The name of bassist Stephan Crump and drummer Eric McPherson’s latest joint venture straight away confirms its relationship to another of their outfits, the Borderlands Trio, and attains a similar level of cohesion. In taking on the role as the third member of the collective, alto saxophonist Darius Jones revels in a rapport every bit as intuitive as pianist Kris Davis, though the character is markedly dissimilar. This is a saxophone trio grounded in the tradition yet liberated from written charts, shaping sonic architecture on-the-fly from repeated cells, extemporized melodies, and mutable riffs.

The setting proves ideal for Jones, whose aching, sour-sweet tone can flare with klaxon authority or drift into lyrical release. His trademark insistence on doubling down on particular phrases – so prominent in his own work – fits hand-in-glove with the outfit’s affinity for accumulating tension only to redirect it into fresh pathways. Crump likewise wrings momentum from reiteration, snapping the music forward with a rhythmic imagination which recalls William Parker in his capacity to unfurl a string of modulating grooves. Together bassist and drummer propose an effortless swinging pulse, unafraid of but not beholden to steady meter. McPherson unites commentary and chase in spacious dialogue that foregrounds timbre and density. Indeed it is his transparency which allows the others to shine as much as they do and which makes this such a pleasing listening experience.

Two long cuts bookend the program, and afford the threesome room to sculpt narrative. After a brooding start, “Metamorpheme” slips into an agreeable lope, Jones’ lines buoyed by the relaxed interplay between bass and drums. In a nod to the saxophone lineage, the performance closes with the saxophonist almost trading breaks with Crump and McPherson. “Imago,” the last track, layers three different tempos which gradually align into a quickening beat. The acceleration pushes Jones into an urgent declamation, only for the passion to give way to Crump’s ominous unaccompanied flurries at the end.

Between times, “Lateral Line” pivots on an arco figure distantly related to Julius Hemphill’s “Dogon A.D.” from which the threesome fashions a fine braided rubato of wavering bass and beseeching saxophone. “Diadromus” centers on emotive vibrato-laden alto runs that edges into multiphonics as the number concludes, while “Instared” functions as a compact mood study, a brief intake of breath before the album’s final ascent. What emerges is a tightly argued but open-hearted recording, assertive without posturing and exploratory without courting extremity. Crump and McPherson continue to cultivate a communal ethos, one that invites collaborators into a process rather than a preset. Jones proves an inspired match for that philosophy, his voice binding the trio through contrast as much as affinity. Davis has appeared in the reedman’s groups, suggesting further possibilities for the future. The Other Borders quartet anyone?

–John Sharpe

Pharoah Sanders

The Complete Pharoah Sanders Theresa Recordings

Mosaic MD7-282

“Pharoah Sanders was an oracle who ministered to many congregations,” Mark Stryker proclaims in his lead for the notes for The Complete Pharoah Sanders Theresa Recordings. His list of constituencies is exhaustive: “Connoisseurs of the avant-garde. Aficionados of mainstream jazz. Art rock and noise rock freaks. Black Nationalists and White Panthers. Hip-hop producers who sample his grooves. Mavens of electronica. World Music buffs. An alliance of aging baby boomers, their children and their children’s children, who all worship the Spiritual Jazz he helped develop ...”

“Pharoah Sanders was an oracle who ministered to many congregations,” Mark Stryker proclaims in his lead for the notes for The Complete Pharoah Sanders Theresa Recordings. His list of constituencies is exhaustive: “Connoisseurs of the avant-garde. Aficionados of mainstream jazz. Art rock and noise rock freaks. Black Nationalists and White Panthers. Hip-hop producers who sample his grooves. Mavens of electronica. World Music buffs. An alliance of aging baby boomers, their children and their children’s children, who all worship the Spiritual Jazz he helped develop ...”

Stryker then poses the question: “Has anyone in jazz except Miles Davis commanded a flock of fans, musicians and cultists of such diverse tastes, persuasions and generations?” Beyond the strange idea that artists command their audiences, the question invites a comparison that wobbles when their respective evolutions are scrutinized. When Miles moved from one approach to the next, it was always all-in. There’s nothing that resembles the work of his rightly fabled quintets in You’re Under Arrest or the early electric groups in Star People, whereas Sanders, particularly on his later albums for Theresa, zig-zagged through disparate soundscapes with confounding results.

Much of what is perplexing and unsatisfying about a good portion of the work included in this seven-disc collection can be blamed on the 1980s. Reagan, MTV, Donkey Kong; a degraded critical environment, compared to those that produced “Strange Fruit” and “Ornithology,” The Freedom Suite and Another Country, LeRoi Jones and Amiri Baraka, or The East and Strata East. Jazz’s market share had dwindled to low single digits. For some African American artists, Quiet Storm and Quincy Jones provided gateways to commercial success, just like rock provided the same for fusioneers. While some of the synths on Sanders’ albums approach a Vangelis-like heavens-opening monumentalism, and some of the grooves are worthy of a Miami Vice night ride, these albums are uncanny in their draw. What would be considered execrable by others is, well, bearable from Sanders. That’s the real point of comparison with latter-day Miles.

Yet, this period also yielded Journey to the One, one of Sanders’ very best, which contained enduring, unostentatious jewels like the joyfully swinging “Greetings to Idris,” the burning “Doktor Pitt,” and the uplifting anthem, “You Got to Have Freedom.” Propelled by the sterling rhythm section of John Hicks, Ray Drummond, and Idris Muhammed, Sanders simply soars, his well-honed solos effortlessly encapsulating his sleek lines and multiphonic squalls. Additionally, the eastward gaze of Sanders’ music is well-represented by succinct tracks accented by koto, sitar, and other Asian instruments, as is his Coltrane roots on wistful readings of “(It’s) Easy to Remember” and “After the Rain” (the latter a duo with Joe Bonner). While there is a foreshadowing of the synthy froth of latter albums with “Think of the One,” Journey to the One arguably makes the most comprehensive case for Sanders’ standing of any single title in his discography.

Theresa returned to the two-disc template that worked so well with Journey to the One for the follow up, Rejoice. The expanded format again allowed Sanders to present in ample portions traditional African music, jazz standards, and his emergent phase of what is now called spiritual jazz (as if some jazz isn’t). Unlike Journey to the One, much of Rejoice was recorded in New York, allowing him to include such luminaries like Art Davis, Billy Higgins, Bobby Hutcherson, and Elvin Jones. Jones appears on only one track, the roiling title piece that opens the proceedings, a potent reminder of how he could not just lift a bandstand, but practically launch it into orbit – and even when he was a bit dampened in the mix, compared to his work with Coltrane and his own Blue Notes. Yet, for every winning track – Sanders’ take on Benny Carter’s “When Lights are Low” is surprisingly lithe and winsome; two duets with Joe Bonner end the collection with deep reflection – there are blemishing, unnecessary touches to other tracks, like the hokey reverberant recitation on the title piece, and the syrupy harp and voices on an otherwise lovely version of “Central Park West.”

Theresa then smartly took advantage of the thriving early 1980s California circuit of venues to produce two successive concert recordings, Live and Heart is a Melody. The energy of Live is measurable in megatons. Leading the charge with Hicks, Muhammad, and Walter Booker, Sanders simply blazes through the opening extended version of “You’ve Got to Have Freedom;” the same is true with the performance of “Dokter Pitt” included on Evidence’s CD reissue from the same week. His touching reading of “(It’s) Easy to Remember,” his gliding, Latin-tinged “Pharomba,” and his robust “Blues for Santa Cruz,” buttress the case that Sanders was not a one-dimensional flamethrower, but a multi-faceted artist, his flag firmly planted at the summit.

The pivot towards excess coincides with the arrival of keyboardist William Henderson in Sanders’ orbit. Even with Muhammad driving Sanders’ new quartet, rounded out by John Heard, the obviously virtuosic, yet rarely rousing, Henderson proved the masterful Hicks to be impossible to follow. This contributes to the side long performance of Coltrane’s “Olé” being less exhilarating and close to exhausting than the longer tracks from the Live dates. Additionally, by virtue of Heart is a Melody being a single disc, Sanders did not have the space to fully flesh out the other facets of his work, resulting in a patchy B side, the highlight being Tadd Dameron’s “On a Misty Night.” And, it was just short of malpractice to omit “Rise and Shine,” the case in point that Sanders had blazing hard bop chops that were too seldom heard (it also features a seriously fierce solo by Muhammad); replacing “Olé” with “Rise and Shine” and the lovely “Naima,” also issued by Evidence, would have brought Heart is a Melody on par with Live.

Fans of Kamasi Washington and latter-day spiritual jazz may point to Shukuru and A Prayer Before Dawn as milestones, but for listeners weaned on the entirety of Sanders’ Impulse catalog – Sumun Bukmun Umyun – Deaf Dumb Blind as well as Karma; and Black Unity as well as Jewels of Thought – they are sorely lacking. Track after track, more proves to be less. The synths and strings and voices are soporific, whether on one of Sanders’ contoured lines or “Body and Soul,” while Sanders’ sound is needlessly sweetened. And – really – Mel Tormé’s “(The) Christmas Song”? The only saving grace on the two albums is Sanders and Hicks’ cover of “After the Rain.”

Sanders’ two appearances as a sideman round out the collection, with the unevenness that is the hallmark of his tenure with Theresa. Ed Kelly & Friend is, as they used to say, a mixed bag: smooth disco-appropriate grooves with popping bass, snappy drumming, and gliding strings and brass sections; lush ballads; Sam Cooke’s “You Send Me,” and yet another version of “You’ve Got to Have Freedom.” A fondly remembered Bay Area pianist and teacher who resisted the lure of New York for family and community, Kelly only had this one opportunity to lead a date – he should have had more. Muhammad enlisted both Sanders and George Coleman for Kabsha, a rousing quartet date with Drummond. The tenors toast rather than joust; the bass and drums are persistent without being overbearing; and, bookended by two equally winning takes of Coleman’s “GCCG Blues,” the program in its original form had a brilliant symmetry. Both tenors were given a spotlight without the other, Sanders’ being a winsome interpretation of “I Want to Talk About You.” Unfortunately, the title composition that only features Coleman was omitted.

–Bill Shoemaker

SAROST

Aurora

Jazz Now JN03SCD

Saxophonist Larry Stabbins’ recent return to active duty has been duly celebrated. He now has to reinforce his standing as a grey eminence in UK improvised music. Cup & Ring, his recent duo recording with Mark Sanders, confirmed his playing to be as strong as ever, but the debut of SAROST, a trio rounded out by the too infrequently heard Paul Rogers, suggests he is actually just getting started. Amid this year’s bumper crop of fine recordings representing this ever-vital community, Aurora stands out, as the trio tempers bold strokes with precise articulation to create music that is both daring and well considered.

Saxophonist Larry Stabbins’ recent return to active duty has been duly celebrated. He now has to reinforce his standing as a grey eminence in UK improvised music. Cup & Ring, his recent duo recording with Mark Sanders, confirmed his playing to be as strong as ever, but the debut of SAROST, a trio rounded out by the too infrequently heard Paul Rogers, suggests he is actually just getting started. Amid this year’s bumper crop of fine recordings representing this ever-vital community, Aurora stands out, as the trio tempers bold strokes with precise articulation to create music that is both daring and well considered.

There is a lot of shared history between these improvisers. Stabbins and Rogers first met in the early 1970s at the National Youth Jazz Orchestra’s summer school. They would reconvene in groups led by John Stevens during his long-standing residency at The Plough later in the decade. They subsequently worked together in a trio with Liam Genocky, Keith Tippett’s Tapestry Orchestra, and in The Dedication Orchestra. Both have played with Sanders in various settings, Rogers most recently in a trio with Paul Dunmall. These longstanding relationships go a long way to explain the cohesive execution and fresh spirit of each of the album’s four improvisations.

One measure of fully matured improvised music is the speed and suppleness an ensemble can coalesce and then move the music to other spaces. In their respective, readily identifiable manners, Stabbins, Rogers, and Sanders take turns being the adhesive to achieve the former and the accelerant for the latter. Their methods vary widely: Stabbins employs everything from ethereal soprano textures to keening tenor lines; Rogers’ unique 7-string instrument spans sub-woofer-like rumble and piercing harmonics; and Sanders again demonstrates that he can start anywhere and go anywhere and retain both the spark of spontaneity and a smart sense of design.

SAROST has the resourcefulness that translates into staying power. Aurora indicates they can have a good run.

–Bill Shoemaker

Norbert Stein Pata Trio

Planetentochter

Pata 27

In the history of improvised and creative music, the saxophone/piano/drums format has some mighty bright beacons: Taylor/Lyons/Murray; the Schlippenbach Trio; and of course, Brötzmann with Van Hove and Bennink. Although with its sole album Planetentochter, one could add German tenor saxophonist Norbert Stein’s Pata Trio (Jörg Fischer, drums; Uwe Oberg, piano) to the list of such trios that can boast a singular identity. Part of the satisfaction that comes from listening to their slim, nearly forty-minute album is that the trio never falls into a standard free improvisation cliché or recipe. Both “Into the Open” and “Life In the Fireplace” open with Stein’s throaty and brawny tenor moving through Ayler-esque fragments and short motifs. On the former he screams and blows blustery gales against pounding piano and busy drums. That is until a nimble, light, and quieter drum solo and delicate piano filigrees come to the fore. On the latter, the trio restrains itself from going full gas, instead transitioning into a quiet middle section. When Stein lets out a scream as “Fireplace” is quietly wrapping up the move becomes an effective surprise rather than something the listener knew was bound to happen.

In the history of improvised and creative music, the saxophone/piano/drums format has some mighty bright beacons: Taylor/Lyons/Murray; the Schlippenbach Trio; and of course, Brötzmann with Van Hove and Bennink. Although with its sole album Planetentochter, one could add German tenor saxophonist Norbert Stein’s Pata Trio (Jörg Fischer, drums; Uwe Oberg, piano) to the list of such trios that can boast a singular identity. Part of the satisfaction that comes from listening to their slim, nearly forty-minute album is that the trio never falls into a standard free improvisation cliché or recipe. Both “Into the Open” and “Life In the Fireplace” open with Stein’s throaty and brawny tenor moving through Ayler-esque fragments and short motifs. On the former he screams and blows blustery gales against pounding piano and busy drums. That is until a nimble, light, and quieter drum solo and delicate piano filigrees come to the fore. On the latter, the trio restrains itself from going full gas, instead transitioning into a quiet middle section. When Stein lets out a scream as “Fireplace” is quietly wrapping up the move becomes an effective surprise rather than something the listener knew was bound to happen.

Planetentochter has few moments of tension and release, and the music rarely follows an easily detectible narrative shape. Each piece deftly moves from section to section, always giving the listener something new. However, rather than fully building different scenes or set pieces and then telling the full story, the trio sets the stage, delivers a few inviting or suggestive lines, and then works on conjuring up another setting. What comes next might not have anything to do with the immediate past or may not serve as a clear transition to the next collection of gestures. It’s not impatience, anxiety, or mania. The trio handles transitions between dynamics and textures and moods in a subtle way that is hard to detect where, why, and how things became different. They just are. The trio’s modus operandi may rest on each member having as much autonomy as possible just up to the point of losing group cohesion. On “Planetentochter” the juxtaposition of Stein’s brittle subtone phrasing against Oberg’s pedal drenched polyrhythmic notes and two hands that are not always in agreement against Fischer’s minimal and color-based drumming is as if each musician is reading the same book, possibly the same chapter, but rarely the same page. Midway through “The Raven Speaks” the trio comes together briefly to support Stein’s catchy repeated phrases and then drift apart; they find each other again and then go their separate ways. The key catalyst may be Fischer removing his snare backbeat out of the pulse. Or it could be Oberg’s incorporation of plucking the interior strings. Correlation? Perhaps. Causation? Probably not. There is not so much conversation or interaction as it is three individuals with half an ear listening toward what could be next. The band is mercurial; their music slippery.

The lack of tried-and-true improvisatory go-to moves demonstrates that this threesome has worked out their own language in which their music is a puzzle for those outside their orbit to enjoy and ponder in their own way. Each listen offers a new set of possible answers, but no definite solutions. A single album is not enough to put the Pata Trio in the same pantheon as Brötzmann and Schlippenbach et al, but Planetentochter is a strong indication that Stein Fischer, and Oberg have the foundation to put together one hell of a run.

–Chris Robinson

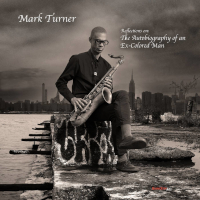

Mark Turner

Reflections On: The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man

Giant Steps Arts GSA20

The last I heard from the marvelous tenor saxophonist Mark Turner was on last year’s fabulous record with Steve Lehman, where the two took on Anthony Braxton’s compositions. On this record, Turner investigates a different archive altogether, in a ten-movement piece based on James Weldon Johnson’s 1912 novel about a biracial man’s ability to pass as white. Featuring tons of text recitation (by Turner), the album’s themes of cultural inheritance, white supremacy, and identity certainly meet the times. But the bulk of the playing time is given over to superb, thoughtful, and often lyrical music by Turner and trumpeter Jason Palmer, keyboardist David Virelles, bassist Matt Brewer, and drummer Nasheet Waits.

The last I heard from the marvelous tenor saxophonist Mark Turner was on last year’s fabulous record with Steve Lehman, where the two took on Anthony Braxton’s compositions. On this record, Turner investigates a different archive altogether, in a ten-movement piece based on James Weldon Johnson’s 1912 novel about a biracial man’s ability to pass as white. Featuring tons of text recitation (by Turner), the album’s themes of cultural inheritance, white supremacy, and identity certainly meet the times. But the bulk of the playing time is given over to superb, thoughtful, and often lyrical music by Turner and trumpeter Jason Palmer, keyboardist David Virelles, bassist Matt Brewer, and drummer Nasheet Waits.

The general mood is largely reflective, which very much fits Turner’s improvisational style. His playing here is so tasteful, spacious, and masterfully controlled. That’s not to say that it lacks intensity or emotion; just listen to the superb opening to “Pulmonary Edema,” for example. More often, though, the music unfolds through vast open space, with soft patter from Waits atop seeping organ. Tension, color, and build are the keywords here, as the music accompanies recitations about anxiety, Southern culture, blood relatives, or, on “Europe,” “music and the race question.” Turner is as attentive and patient with text as with notes, with an admirable sense of cadence and phrasing. The text is also integrated really thoughtfully, with beautifully songful lines flowing in and out (“Juxtaposition”) or some earthy, testifying sound that’s perfect for “New York.” Throughout, it’s a joy to listen to Turner and Palmer together, cavorting with the beautiful pulses laid down by Brewer and Waits, or responding to Virelles’ unpredictable turns – a craggy piano solo, some swirling organ, or some brooding commentary on the text.

Often, the music has a Wayne vibe in its close harmonies and enigmatic feel. And even when the band occasionally sprints, none of the playing feels rushed. The flow and harmonic imagination are ceaseless, whether in ballads like “Mother . . . Sister . . . Lover” or the sweeping “Identity Politics.” It’s a real accomplishment, this record, elegantly constructed but deeply affecting emotionally.

–Jason Bivins