A Fickle Sonance

a column by

Art Lange

Xavier Charles Gerard Rouy©2006

It would be silly, I suppose, to claim that the clarinet is making a resurgence in improvised music—after all, it has hardly waned since the 1960s, a decade which saw Jimmy Giuffre follow his most abstract ‘50s inclinations into a stunning trio with pianist Paul Bley and bassist Steve Swallow, the always-radical traditionalist Pee Wee Russell boldly venture into Coltrane and Monk repertoire, and the recording debuts of John Carter and Perry Robinson. And yet, outside of today’s hale-and-hearty worldwide crew of New Orleans-style archeologists, the multi-reed part-timers (think Braxton, Brötzmann, or even Bob Wilber), the survivors (we just lost Kenny Davern, but Tony Scott and Buddy De Franco are still, remarkably, hanging in there as of this writing), and the subsequent generations of active jazzers from Theo Jörgensmann to Don Byron, it nevertheless appears that a clutch of clarinetists have recently refreshed the idea of commingling jazz and classical music devices, to interesting and unexpected ends. That the trio format, with varying instrumentation sans drums, is the primary ensemble of choice is another thread that unifies these five distinctive players, and suggests that Giuffre’s influence is still strong.

I remember reviewing Andy Biskin’s debut album Dogmental (GM Recordings) in Pulse on its release several years ago, and being impressed by the clarinetist’s writing chops as well as his playing. This is no less true on Trio Tragico (Strudelmedia), which offers a variety of redesigned song and dance forms. Biskin frequently sets his warm-toned clarinet against Dave Ballou’s trumpet and Drew Gress’ bass in three-part counterpoint, and pens multi-sectional, stop-and-start pieces that touch upon tango, waltz, polka, postbop, blues, and free resources. The trio has a compact, intimate feel more like a chamber group than a jazz band—there is an occasional jazz lilt if not outright swing, and if it feels initially that the soloists are constrained by their surroundings, the melodic curves and rhythmic juxtapositions challenge them to find solutions that are concise, poised, winsomely lyrical, and fit into the arrangements hand-in-glove.

In contrast, the solos on bassist Reuben Radding’s Intersections (Pine Ear Music) are intended to test the nature of the compositions; themes are often somber and long-limbed, with large interval leaps that inspire the trio to stretch phrasing and loosen tempo to the point of open-ended entanglements that spontaneously reshape the music from the inside. Matt Moran’s vibes brighten the ensemble palette, whether in rattling, resonating solos, bowed to create hazy, shimmering harmonics, or sparsely yet percussively comping underneath Oscar Noriega’s deft, rhapsodic, slightly tart clarinet. The key to Radding’s compositional approach lies in the program’s final piece—an arrangement of the sixth movement of Messiaen’s Quatuor pour la fin du Temps, where the extended melody is given a light swing feel and used as a “head” for solos, while motifs are fragmented and abstracted to serve as accompaniment. Throughout the disc, the trio alternates between this chromatic harmonic syntax and Webernesque melodic contours spun like spider webs, upon which they improvise with tightly focused interaction.

John Rangecroft is a member of the British free improvisation community and contributor to several of Evan Parker’s projects of recent vintage. On Parker’s Crossing The River (psi), the eight participants mix and match from duo to octet; Rangecroft’s trio performance finds his clarinet’s linear, melismatic, angular phrasing counterpointing the brittle, bristling attacks of guitarist John Russell and bassist John Edwards. On Free Zone Appleby 2002 (psi), documenting several ad hoc groups from the Appleby Jazz Festival, he jousts with Parker’s soprano saxophone, thrusting complimentary figures against Parker’s repetitive motifs, and gradually tugging him towards looser climes, lines twisting like clinging vines. In larger groups, quartet and octet, he blends his tone color into the clutter of sounds, holding long tones as if treading water as others swim against the tide. When faced with a drummer (one cut on Free Zone Appleby 2002 and throughout his own 1996 trio album Blythe Hill [Slam]), his lines become less pastoral and take on more sinew, with tonal qualities resembling bassoon or soprano saxophone, and a tenacious push, reminiscent of John Carter, that increases rhythmic tension and drive.

Better known as a saxophonist, Ken Vandermark’s Free Fall (with pianist Håvard Wiik and bassist Ingebrigt Håker Flaten), named after Jimmy Giuffre’s freest trio album, is devoted solely to his Bb and bass clarinets. The pull of Eric Dolphy on his bass clarinet is apparent—he exhibits a wider range of gestures on the smaller horn, either following the Impressionist intimations of pianist Wiik or his own extroverted impulses. On Amsterdam Funk (Smalltown Superjazz) the trio alternates between composed strategies and brief, freely improvised “frameworks.” It’s hard to tell the difference, as the composed pieces allow plenty of space for intuitive responses. One such composition finds Vandermark softening his sound as he bends and swallows pitches in homage to Giuffre, but elsewhere his piping tone intensifies the ensemble mood, whether squealing into free figures or doubling the ostinato patterns of bassist Håken Flaten.

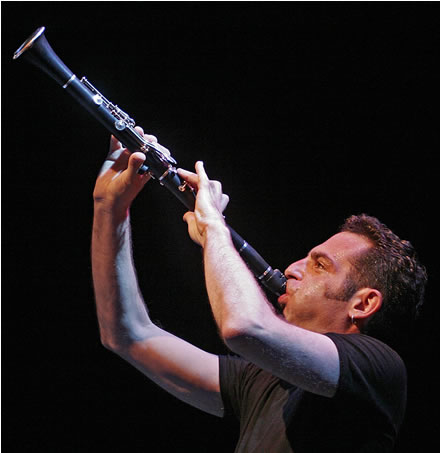

Of these five clarinetists, only Xavier Charles limits himself to extended techniques in his texturally-based trio with saxophonist John Butcher and trumpeter Axel Dörner. Live and studio tapes of the group are edited and manipulated on The Contest of Pleasures (Potlatch) so that the acoustic ensemble evokes fascinating electronic timbres and a musique concrète ambience, eschewing set rhythms for a fluid awareness of silence and space, and reconfiguring pitches into layered tones and morphing waves of sound. Charles has collaborated with electronic musicians Kristoff K. Roll (Jean-Christophe Camps and Carole Rieussec) to similar Xenakis-like effect on La Pièce (Potlatch), but a better display of his dramatic, distorted-pitch improvising abilities may be heard on Ethos (La belle du quai), alongside pianist Fédéric Blondy and bassist Davis Chies.

Giuffre notwithstanding, it’s impossible to think of the clarinet without calling to mind Johnny Dodds and Benny Goodman, Pee Wee Russell and George Lewis as well. Despite its rich jazz legacy, is there something about the clarinet that makes it susceptible to contemporary classical influences? I think so. While the range of tones it can produce—from breathy transparency to throaty growl, and all the stages in between—suits the full spectrum of jazz expression, there’s also a purity and intimacy to its voice that make seemingly dissonant intervals seductive and lends warmth to a pointillist atonal line that needn’t swing to sustain momentum. If classical composers from Brahms to Boulez have devised effective settings for its woody resonance, why shouldn’t improvising musicians adapt them to their own ends? After all, isn’t that what jazz has always done?

Art Lange©2006