Moment's Notice

Reviews of Recent Recordings

(continued)

Luis Lopes Humanization 4tet

Believe, Believe

Clean Feed CF549CD

Tenor saxist Rodrigo Amado grabs you from the very beginning of this set. His sound is big, he barrels ahead with great energy, his mainstream-outside lines suggest funky bop as well as it does post-Ayler, post-Trane. He repeats himself often and he is totally unsubtle. Since so much of this album is tenor-guitar duo improvisation with accompaniment, the contrast with guitarist Luis Lopes couldn’t be more vivid. Lopes is utterly rhythmically and harmonically free, now and then atonal. Guitar tones, chords sparkle out of nowhere, or he underlines, decorates, or mocks. His volume is down low, to emphasize the contrast. His brief solo passages are dotted with distorted-sound accents, which lend dramatic intrigue. Together, the Portuguese saxophonist and guitarist are a roughneck and a clever pal.

Tenor saxist Rodrigo Amado grabs you from the very beginning of this set. His sound is big, he barrels ahead with great energy, his mainstream-outside lines suggest funky bop as well as it does post-Ayler, post-Trane. He repeats himself often and he is totally unsubtle. Since so much of this album is tenor-guitar duo improvisation with accompaniment, the contrast with guitarist Luis Lopes couldn’t be more vivid. Lopes is utterly rhythmically and harmonically free, now and then atonal. Guitar tones, chords sparkle out of nowhere, or he underlines, decorates, or mocks. His volume is down low, to emphasize the contrast. His brief solo passages are dotted with distorted-sound accents, which lend dramatic intrigue. Together, the Portuguese saxophonist and guitarist are a roughneck and a clever pal.

Very much of the pleasure of this CD comes from two American eel-yellers, bassist Aaron and drummer Stefan Gonzalez. The ballad “She” is quiet enough to showcase Aaron. He’s unamplified, he loves the true sound of the bass, but probably like most bassists between such strong drums and tenor, he doesn’t project well. His lines are active and lyrical and his senses of free rhythmic movement and tonality match Lopes’ instincts – a bit of nice strings duetting. Otherwise, from beginning to end the album is filled with the percussion of Stephan, who suggests the dynamism and freedom of his former percussion associate Alvin Fielder. It’s a thick, rich layer of sound that propels the others while remaining responsive, as in passing duets with Amado. The opening piece “Eddie Harris/Tranquilidad Alborotadora” is longest and shows Stephan, Amado, and Lopes at their best, with lyrical passages by Amado and quiet guitar fireworks.

–John Litweiler

Rudresh Mahanthappa

Hero Trio

Whirlwind Recordings WR4760

Alto saxophonist Rudresh Mahanthappa pays homage to his formative influences on Hero Trio, an album of interpretations named in honor of his musical heroes. A companion to Bird Calls (ACT Records, 2015), which featured original compositions inspired by the work of Charlie Parker, Hero Trio is Mahanthappa’s sixteenth release as a leader/co-leader, but first to exclusively feature covers. In addition to Parker, the program also pays tribute to John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Keith Jarrett, Sonny Rollins, Stevie Wonder, and Johnny Cash. To explore these original arrangements, Mahanthappa enlisted bassist François Moutin and drummer Rudy Royston, with whom he shares a long history. Free from chords, the trio expounds on these songs with harmonically unfettered verve.

Alto saxophonist Rudresh Mahanthappa pays homage to his formative influences on Hero Trio, an album of interpretations named in honor of his musical heroes. A companion to Bird Calls (ACT Records, 2015), which featured original compositions inspired by the work of Charlie Parker, Hero Trio is Mahanthappa’s sixteenth release as a leader/co-leader, but first to exclusively feature covers. In addition to Parker, the program also pays tribute to John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Keith Jarrett, Sonny Rollins, Stevie Wonder, and Johnny Cash. To explore these original arrangements, Mahanthappa enlisted bassist François Moutin and drummer Rudy Royston, with whom he shares a long history. Free from chords, the trio expounds on these songs with harmonically unfettered verve.

Mahanthappa acknowledged his debt to Charlie Parker on Bird Calls, reimagining Parker’s canon in a modernist light. Here legacy is more explicit, with a dazzlingly rearranged version of Parker’s “Red Cross” kicking off the album. Rife with stops, starts, and sharply veering asides, it launches into an expansive groove that’s more funk than bebop. A funky take on “Barbados” is conjoined to John Coltrane’s “26-2,” transforming breakneck bebop into sheets of sound, while a bracing “Dewey Square” merges bebop with a shifting rhythmic structure that pivots between swing and funk.

Other standards include an aching rendition of Coleman’s “Sadness,” with sonorous bowed bass, wavering alto, and soft mallets; a lively version of Jarrett’s “The Windup,” that spotlights Moutin’s resonant pizzicato; and a dirge-like interpretation of “I Can’t Get Started,” featuring Mahanthappa’s introspective intro. The group’s focused intensity shines on a keen arrangement of “I’ll Remember April,” a standard associated with both Parker and Rollins. Mahanthappa surges atop a relentless syncopated vamp in 9/8 that gives way to the swinging theme, his quicksilver alto bobbing and weaving between the two grooves, venturing outward bound, while Moutin and Royston hold down the foundation.

Two surprises stand out: a Danilo Pérez-arranged version of Stevie Wonder’s “Overjoyed,” and Mahanthappa’s take on the June Carter Cash/Merle Kilgore hit “Ring of Fire.” Although novel detours, neither are entirely successful. The unadorned melody of “Overjoyed” suffers when translated from pop to jazz, although Mahanthappa’s plangent tone does reach lyrical heights that recall the work of Marty Ehrlich. The same dilemma hinders Mahanthappa’s straightforward interpretation of “Ring of Fire,” whose plain harmonic structure becomes a liability when used as a springboard for advanced improvisation. Although Mahanthappa’s decision to include pop songs is questionable, the trio invests the remaining standards with exceptional vitality worthy of repeated spins.

–Troy Collins

Simon Nabatov

Plain

Clean Feed CF546CD

Pianist and composer Nabatov has one of the best batting averages in the music, but somehow never quite seems to get the attention he merits. A prodigious technician, a lover of quirky repertory, and always the beneficiary of a cracking band, Nabatov brings together all the elements I generally look for. And simply put, Plain is one of his best in recent years. He’s joined by Chris Speed on tenor and clarinet, trumpeter Herb Robertson, and the telepathic team of bassist John Hébert and drummer Tom Rainey.

Pianist and composer Nabatov has one of the best batting averages in the music, but somehow never quite seems to get the attention he merits. A prodigious technician, a lover of quirky repertory, and always the beneficiary of a cracking band, Nabatov brings together all the elements I generally look for. And simply put, Plain is one of his best in recent years. He’s joined by Chris Speed on tenor and clarinet, trumpeter Herb Robertson, and the telepathic team of bassist John Hébert and drummer Tom Rainey.

The date starts off with the title track, featuring an exploratory, tonally ambiguous duet between Nabatov and Speed’s sinuous clarinet. There’s marvelous simpatico among the whole group, no small feat given how different the personalities are. Needless to say, the bassist and drummer are well versed in playing together, but the singular contributions of Robertson especially bring such flavor to these tunes, whether it’s in rambunctious swing or the faint melancholy of the track’s ending.

Many of the tunes are of the tough-to-navigate sort that combine serious textural experimentation with a noticeable density of line or notation. In “Copy That,” for example, the quintet falls into dark clouds, filled with glissandi and smears. They ride a pedal point that stops on a dime for a sparse, pointillistic turn. Then there’s quick trading and unisons of “Cry from Hell” filled with crisp snare and clarinet chirps. These tunes feel so natural, but they are brash and inventive in their construction and in the improvising, whether it’s the spacious drift of “Break” or the outrageous “Ramblin’ On,” which finds Robertson – in his best Waits/Beefheart voice – hollering through a bullhorn.

Beautiful rhythmic shapes emerge organically, often playfully in this music. It ranges from rhapsody to churn, from hush to clangor. The wide-ranging “Slow Thinker,” for example, has the horns playing aching long lines over lovely brushwork before multiple curveballs speed things into and out of abstraction. And, fittingly given Nabatov’s influences, the date is capped off with a lively stroll through Herbie Nichols’ “House Party Starting,” Nabatov gleefully leaning into the familiar theme with playful asides, tempo shifts, and bracingly swift runs. As captivating as the rhythmic and harmonic variations from his bandmates are, it’s Nabatov who compels throughout this performance, right down to the last lingering notes of the gloriously lyrical solo piano coda.

–Jason Bivins

New York Contemporary Five

Consequences Revisited

ezz-thetics 1105

That an album calls to be revisited at all suggests at once both its presumed value and its erstwhile neglect. It also evokes, perhaps, a form of learned listening, calling upon the careful judgement of the serious connoisseur. And yet, when we put on Consequences Revisited by the New York Contemporary Five (NYC5) – a recent reissue on Hat Hut’s excellent Revisited series – the music that comes tumbling out of the speakers carries a shock and an urgency that unsettles any hope of tranquil contemplation. There is a hole in the bottom of this music. Or rather you can almost hear the bottom falling out of it: a frantic brilliance casting out over and over. And yet for all its fire and searching, for all its newness (albeit almost 60 years old), it is nonetheless inhabited by ghosts of the past. Abstraction rubs up against nursery rhymes. (blues and the abstract truth.) Or to borrow Archie Shepp’s description of Ornette Coleman’s music, it sounds like “a square dance telescoped through the barrel of a machine gun.”

That an album calls to be revisited at all suggests at once both its presumed value and its erstwhile neglect. It also evokes, perhaps, a form of learned listening, calling upon the careful judgement of the serious connoisseur. And yet, when we put on Consequences Revisited by the New York Contemporary Five (NYC5) – a recent reissue on Hat Hut’s excellent Revisited series – the music that comes tumbling out of the speakers carries a shock and an urgency that unsettles any hope of tranquil contemplation. There is a hole in the bottom of this music. Or rather you can almost hear the bottom falling out of it: a frantic brilliance casting out over and over. And yet for all its fire and searching, for all its newness (albeit almost 60 years old), it is nonetheless inhabited by ghosts of the past. Abstraction rubs up against nursery rhymes. (blues and the abstract truth.) Or to borrow Archie Shepp’s description of Ornette Coleman’s music, it sounds like “a square dance telescoped through the barrel of a machine gun.”

Certainly, the album’s opening track, “Sound Barrier” (aka “Cisum”), composed by the group’s cornetist Don Cherry, bears the mark of his mentor. The melody combines clarion calls (the three horns echoing each other to form a piercing unison) with nursery rhyme fragments broken into constantly shifting tonal centers, sometimes moving in Monk-esque half-steps. It’s the kind of modular melody that sings of Cherry’s debt to Ornette – the disjointed parts fitting together so miraculously that you start to question where one finishes and the other begins. The other compositions on the album – by John Tchicai (on alto), Archie Shepp (on tenor), Thelonious Monk (another of the group’s other major influences besides Ornette), and Bill Dixon (arranger of the first 6 tracks) – corroborate Amiri Baraka’s hypothesis upon hearing the NYC5 in concert that “[t]his new band ought to have a pretty wild book...”

In being revisited by this music, it is worth bearing in mind that the NYC5 was born and died at the height of a treacherous period in which the New Thing emerged into a jazz scene that was losing its commercial viability and had not yet secured any institutional support. As Erik Wiedemann pointed out in the liner notes to the group’s self-titled Sonet release in 1963, almost no club in New York was interested in booking them, so they formed for an engagement in Copenhagen. (On this reissue, Bill Shoemaker’s informative text fills out the details of the group’s story.) Shepp put it this way: “This is where the avant-garde, begins. It is not a movement but a state of mind.” An insistent searching somewhere between hunger and freedom. These recordings contain a piece of that searching: the sound of a generation stretching out before our ears – stretching the music, themselves, their instruments, the tradition. And it calls to be revisited.

–Gabriel Bristow

Potsa Lotsa XL

Silk Songs for Space Dogs

Leo 878

The resourceful alto saxophonist and composer Silke Eberhard has led a wide variety of sessions, ranging from post-bop quartets to repertory takes on Ornette Coleman or Eric Dolphy. Her Potsa Lotsa group has come in all shapes and sizes over the years, and for this outrageously good Leo date, PL is XL. Joining Eberhard are: Juergen Kupke (clarinet), Patrick Braun (tenor sax and clarinet), Nikolaus Neuser (trumpet), Gerhard Gschloessl (trombone), Johannes Fink (cello), Taiko Saito (vibraphone), Antonis Anissegos (piano), Igor Spallati (bass), and Kay Luebke (drums). The absolute star of this date, though, is Eberhard the composer and arranger.

The resourceful alto saxophonist and composer Silke Eberhard has led a wide variety of sessions, ranging from post-bop quartets to repertory takes on Ornette Coleman or Eric Dolphy. Her Potsa Lotsa group has come in all shapes and sizes over the years, and for this outrageously good Leo date, PL is XL. Joining Eberhard are: Juergen Kupke (clarinet), Patrick Braun (tenor sax and clarinet), Nikolaus Neuser (trumpet), Gerhard Gschloessl (trombone), Johannes Fink (cello), Taiko Saito (vibraphone), Antonis Anissegos (piano), Igor Spallati (bass), and Kay Luebke (drums). The absolute star of this date, though, is Eberhard the composer and arranger.

The opening “Max Bialystock” (and Zero Mostel’s loony character gives you some indication as to the brio of Eberhard’s music) is a riot of counterpoint, an astoundingly rich sound-field that makes full use of the dynamic ensemble. Complexity and contrast are on full display, but Eberhard’s tunes swing, if oddly (Spallati and Luebke sound great, but Anissegos and especially Saito are consistently riveting players). Eberhard, who takes a cracking solo here, is audibly fond of the robust rhythmic language of Third Stream composers like Gunter Schuller and George Russell, whose continual motion and transformation is balanced with the freshness and exuberance of spontaneous improvising.

No inessential details here, just pure energy and invention. The counter lines that open “Crossing Colours” are infectious, the tight snare patterns and snaking piano setting up some boisterous work from the horns (Neuser in particular is killer). Ranging and rolling, it turns on a marvelously paced drum solo, and everywhere there are just loads of dynamic shifts that give real power to the charts. “Skeletons and Silhouettes” opens with a really slinky noirish lope, and boasts some exceptional cello/trombone unisons (Fink also tees up a terrific solo, skittering manically over the elegance).

“Fuenfer, or Higher you Animals” is filled with unexpected moves. I was knocked out by the Steve Reich-level skeins of piano and vibes, shifting meters until a climax yields an unexpected, achingly soft denouement. There’s a lot to process, even as the music feels direct and natural. Changes seem to sneak up on you, whether it’s the elegant chord changes wending their way through “Ecstasy on Your Feet,” the Gil Evans-like voicings on the patient, steady procession of “Schirm,” or the duos that seem to bloom out of nowhere, a righteous clarinet and vibes dialogue here, a cello and trombone work out there.

On top of the music’s sheer inventiveness, its individual and collective statements, 2020 positively demands that I emphasize what a fun record this is. I found myself laughing at how many turns it takes, and muttered “sweet!” to myself at least once per track. I can only imagine how enjoyable PLXL would be live. For now, at least I can enjoy one of my favorite records of the year so far.

–Jason Bivins

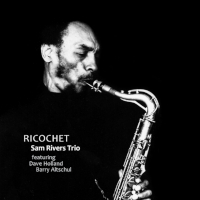

Sam Rivers Trio

Ricochet

NoBusiness NBCD 128

It’s taken until NoBusiness Records’ third selection from Sam Rivers’ personal archive for the spotlight to solely settle on the classic trio perhaps most associated with the multi-instrumentalist, the one completed by bassist Dave Holland and drummer Barry Altschul (though both appeared as part of a quintet on a 1977 concert from Berlin, under the title Zenith, issued last year). Appreciation of their value wasn’t confined to Rivers, as the pair also furnished the rhythm section for the group Circle with pianist Chick Corea and reedman Anthony Braxton, as well as Braxton’s subsequent quartets. But it was Rivers’ trio which persisted longest, with Holland equating it to a finishing school.

It’s taken until NoBusiness Records’ third selection from Sam Rivers’ personal archive for the spotlight to solely settle on the classic trio perhaps most associated with the multi-instrumentalist, the one completed by bassist Dave Holland and drummer Barry Altschul (though both appeared as part of a quintet on a 1977 concert from Berlin, under the title Zenith, issued last year). Appreciation of their value wasn’t confined to Rivers, as the pair also furnished the rhythm section for the group Circle with pianist Chick Corea and reedman Anthony Braxton, as well as Braxton’s subsequent quartets. But it was Rivers’ trio which persisted longest, with Holland equating it to a finishing school.

Ricochet presents the triumvirate on a single set long piece, recorded live at San Francisco’s Keystone Korner in 1976. As typical for Rivers, he employs each of his four axes in the collective improvisation which organically shifts between fiery freeform and spontaneous groove. On bass, and briefly cello, Holland parades his A-game throughout, whether in astute counterpoint, kinetic riff or angular sawing. It’s Altschul who is probably least well-served by the recording, with his trap set slightly distant, though his musicianship is similarly inspired.

This outfit could write the book on trio interplay. They change gears smoothly between the scorching opening, replete with Rivers’ emotive soprano saxophone cries, a rubato episode of responsive dialogue with Holland wielding his bow, and a dancing passage in which Rivers unspools an undulating tale with lyric inflections. Even when Holland diverges from the vamp, the swinging impulse remains. Transitions too are handled with such aplomb that they might be preordained. Witness how Holland’s sure-footed unaccompanied bass excursion closes with the repeated pattern which cues Altschul and Rivers to rejoin, this time with the leader on piano.

In fact, this disc contains some of Rivers’ most fully realized work on the 88-keys, as he develops a perfect balance between rhythmic energy and melodic variation, encompassing bluesy lilt, swaying calypso and wayward stride. Other fine moments include the invigorating cries of intertwined cello and tenor saxophone, and the final straight where Rivers’ buoyant flute almost trades fours with Holland’s pizzicato, supported by Altschul’s drum boogaloo, demonstrating how their hard-won freedom was grounded in mastery of convention.

Such events amid the magnificent flow make this outing one of the most satisfying performances from these three titans.

–John Sharpe