Moment's Notice

Reviews of Recent Recordings

(continued)

Illegal Crowns

Illegal Crowns

RogueArt ROG-0066

Taylor Ho Bynum, guitarist Mary Halvorson, pianist Benoit Delbeq, and drummer Tomas Fujiwara – improvise and interact with relaxed alertness, finely judging time, texture, line, and ensemble density to make music comprised of separate personal voices that cohere into a lively whole. Their every gesture is defined, specific, and placed within the flow of music so it harmonizes with what surrounds it. Sure there’s tension and release and dissonance and noise, but there’s never a clash or an element out of place.

Taylor Ho Bynum, guitarist Mary Halvorson, pianist Benoit Delbeq, and drummer Tomas Fujiwara – improvise and interact with relaxed alertness, finely judging time, texture, line, and ensemble density to make music comprised of separate personal voices that cohere into a lively whole. Their every gesture is defined, specific, and placed within the flow of music so it harmonizes with what surrounds it. Sure there’s tension and release and dissonance and noise, but there’s never a clash or an element out of place.

On Benoit Delbeq’s “Colle & Acrylique,” for example, the composer’s prepared piano toys with an ostinato pattern, generating modulating rhythms with the clanking timbre of dancing pots and pans. Halvorson’s spidery vines trace zig-zag lines that suddenly bloom into translucent, broad flowers of sound, or detune and curl up like fall leaves. Fujiwara’s rocky soil of tom tom patter and cymbal splashes and the misty sky of Bynum’s muted trumpet complete a landscape painted in subtle colors and light and shade. It sounds effortlessly executed yet it’s too refined, too balanced and coordinated to be anything but the result of hard-won virtuosity and deep listening.

The other tracks each open up some new proposition for group discourse. The group’s improvising on Fujiwara’s “Wry Tulips” and Halvorson’s “Illegal Crowns” bleeds into various ensemble configurations or shift direction with a collective unity of purpose that’s breathtaking. Their unhurried cat and mouse play with meters and tempos on Halvorson’s “Solar Mail,” helps the piece evolve consensually and deliberately. The jig saw puzzle pieces of melody and tone color – some written, some improvised – fit so snugly together on Delbeq’s “Holograms,” that the boundary between written and improvised dissolves.

In many ways the music can be heard as the ripening of seeds sown in previous decades by the improvised music avant-garde. Illegal Crowns are at home in a collectively improvised environment without set roles for instruments or set rules about what sounds can be included or excluded as music. Likewise they live in a musical world where the relationship between composed and improvised can be continuously interrogated and where classical, jazz, popular, and folk musics from anywhere in the world are accepted as legitimate resources to use within a composition or an improvisation. All the ambiguities and boundless potential offered by these freedoms are their inheritance. What we hear in the music is not primarily the struggle and excitement of innovation, but more the delight of exploring a rich world full of surprise and unexpected challenges, one in which the players feel quite at home. With so much to drawn on, so much to discover, so many mysteries to solve, there’s never a dull moment.

–Ed Hazell

Joe McPhee

Flowers

Cipsela 005

Joe McPhee’s solo albums are always a treat, and finding him with his alto alone on Flowers is an especial rarity. It is, as is McPhee’s custom, earthy and expansive, filled with familiar repertory pieces as well as bold first appearances, all shot through with his irresistible lyricism. There’s wonderful focus and feel throughout, abetted by the nicely resonant recording from the Museu Nacional Machado de Castro, at an opening for Niklaus Troxler’s paintings as part of the Coimbra Festival. Troxler is also the dedicatee on “Knox,” lovingly, patiently explored here (and also the well-loved lead-off track on McPhee’s classic, Tenor). Soft breath and keypads open “Eight Street and Avenue C,” dedicated to Alton Pickens. From an initial statement of avian metallophone squeak and overtones, McPhee patiently elaborates a series of lines, craggy intervals, and some soulful lyricism, the grain of the horn really suiting the musical decisions he makes. This is a virtue that’s apparent all across these performances, ranging from honking to soft flutter, from vocalized overtone harshness to mellow lines in the sweet spot. With regard to the latter, there’s a rapturous transformation of the great “Old Eyes,” with McPhee really giving some lift to the notes that cap each lush phrase (and he evens puts some “Dancing in Your Head” quotes in there). There’s some beautiful wailing on the tune for Tchicai, “Flowers.” After this, McPhee backs off into the near total silence of “The Whistler,” with masterful control of overtones and dynamics, before a forceful churn closes that piece out. Near the set’s conclusion, McPhee addresses the rapt audience and wonders “What should we do?” His response, a dedication to Julius Hemphill, is to clap hands (or is it tap dancing) briefly before closing the set as he opened it. A great date, one to savor.

Joe McPhee’s solo albums are always a treat, and finding him with his alto alone on Flowers is an especial rarity. It is, as is McPhee’s custom, earthy and expansive, filled with familiar repertory pieces as well as bold first appearances, all shot through with his irresistible lyricism. There’s wonderful focus and feel throughout, abetted by the nicely resonant recording from the Museu Nacional Machado de Castro, at an opening for Niklaus Troxler’s paintings as part of the Coimbra Festival. Troxler is also the dedicatee on “Knox,” lovingly, patiently explored here (and also the well-loved lead-off track on McPhee’s classic, Tenor). Soft breath and keypads open “Eight Street and Avenue C,” dedicated to Alton Pickens. From an initial statement of avian metallophone squeak and overtones, McPhee patiently elaborates a series of lines, craggy intervals, and some soulful lyricism, the grain of the horn really suiting the musical decisions he makes. This is a virtue that’s apparent all across these performances, ranging from honking to soft flutter, from vocalized overtone harshness to mellow lines in the sweet spot. With regard to the latter, there’s a rapturous transformation of the great “Old Eyes,” with McPhee really giving some lift to the notes that cap each lush phrase (and he evens puts some “Dancing in Your Head” quotes in there). There’s some beautiful wailing on the tune for Tchicai, “Flowers.” After this, McPhee backs off into the near total silence of “The Whistler,” with masterful control of overtones and dynamics, before a forceful churn closes that piece out. Near the set’s conclusion, McPhee addresses the rapt audience and wonders “What should we do?” His response, a dedication to Julius Hemphill, is to clap hands (or is it tap dancing) briefly before closing the set as he opened it. A great date, one to savor.

–Jason Bivins

Rova::Orkestrova

No Favorites!

New World 80782-2

For a group that’s been around for as long as Rova has, it’s mighty impressive that Mssrs. Ackley, Adams, Ochs, and Raskin continue to explore so many different groups and associations. Their Orkestrova settings are invariably challenging and impressive, and No Favorites! convenes a large group of Bay Area improvisers, with long associations of their own as well as (in several cases) connections to the late, lamented Lawrence D. “Butch” Morris, to whom this recording is dedicated. Along with the saxophonists, the ambitious date includes violist Tara Flandreau, violinist Christina Stanley, cellist Alex Kelly, bassist Scott Walton, guitarist John Shiurba (always a pleasure), and Fred Frith’s current bandmates, electric bassist Jason Hoopes and drummer Jordan Glenn.

For a group that’s been around for as long as Rova has, it’s mighty impressive that Mssrs. Ackley, Adams, Ochs, and Raskin continue to explore so many different groups and associations. Their Orkestrova settings are invariably challenging and impressive, and No Favorites! convenes a large group of Bay Area improvisers, with long associations of their own as well as (in several cases) connections to the late, lamented Lawrence D. “Butch” Morris, to whom this recording is dedicated. Along with the saxophonists, the ambitious date includes violist Tara Flandreau, violinist Christina Stanley, cellist Alex Kelly, bassist Scott Walton, guitarist John Shiurba (always a pleasure), and Fred Frith’s current bandmates, electric bassist Jason Hoopes and drummer Jordan Glenn.

On the opening “Nothing Stopped/But A Future (for Buckminster Fuller)” (penned by

Ochs and conducted by Gino Robair) one can immediately detect the influences of Morris, who was all about maximal color fields, textural range, and smart instrumental groupings. It’s effective in particular in the strings playing here, mournful and lyrical in some places, furiously scratching in others. Like the other pieces here, this one is complex and ever-moving, filled with beautiful dynamics and quite difficult transitions, all handled with aplomb by the smart, sensitive Robair. But regardless of how many different places it goes – stuttering rhythms, boiling multi-directional horns – it’s all unified by the intense conviction of the players and by the piece’s own directional ascent, rising from staccato drums into a huge horn fanfare and a maximum density chordal ending.

“The Double Negative” (co-composed by Adams and Raskin) opens with delicate strings pointillism, contrasting pizzicato and high keening as other musicians join steadily in layers to conjure an unsettled and tense atmosphere. Intervals and elegant sax lines move in and out of the foreground, providing structure and improvisational reference points. Lines increase in number and density, weaving in and out of each other until along come Shiurba and Hoopes to activate their twittering machines. It’s a marvelous study in contrast. And then, almost out of nowhere, it’s like all the varied elements are sucked into a great humming cloud of sound, with occasional percussive declamations. The long Rova-composed piece “Contours of the Glass Head” opens by contrasting furious electronic scrabble with the stateliest, most elegant horns and strings. At length, the gnashing and the wailing take the lead, and there’s some especially intense stuff from Glenn and Flandreau. With great big slashes, the engine heats up and then – in another of the marvelous coalescences heard on these pieces – unfurls in a long ensemble gliss that recalls Giacinto Scelsi. With an “anything is possible” aesthetic over nearly half an hour, the piece goes to all kinds of places. Paradiddles and trills endeavor to withstand white noise. A harmolodic guitar trio matches wits with a hyper-drive Braxtonian pulse track. And intense improvisations scuffle over an almost hymnal tone-bath. When the album ends in an abrupt, crystalline punctuation, it’s almost hard to get your bearings again. But it’s hard not to be intoxicated by such head-scrambling exploration.

–Jason Bivins

Elliott Sharp Aggregat + Barry Altschul

Dialectrical

Clean Feed CF386CD

The 2013 Clean Feed release of Elliott Sharp’s Quintet marked the first time the veteran multi-instrumentalist issued an album that found him performing exclusively on saxophones and clarinet. The session featured a somewhat traditional jazz combo; trumpeter Nate Wooley and trombonist Terry L. Green joined the leader as part of a three-horn frontline, supported by bassist Brad Jones and drummer Ches Smith. Despite the relatively conventional instrumentation, the results were expectedly avant-garde (unsurprising, considering Sharp’s oeuvre), alternating between kinetic expressionism and aleatoric impressionism.

The 2013 Clean Feed release of Elliott Sharp’s Quintet marked the first time the veteran multi-instrumentalist issued an album that found him performing exclusively on saxophones and clarinet. The session featured a somewhat traditional jazz combo; trumpeter Nate Wooley and trombonist Terry L. Green joined the leader as part of a three-horn frontline, supported by bassist Brad Jones and drummer Ches Smith. Despite the relatively conventional instrumentation, the results were expectedly avant-garde (unsurprising, considering Sharp’s oeuvre), alternating between kinetic expressionism and aleatoric impressionism.

Diaelectrical, Sharp’s third offering with his Aggregat ensemble, is aesthetically similar to the former release, albeit with a notable change in personnel. With Wooley and Smith unavailable for this date, Sharp recruited trumpeter Taylor Ho Bynum and legendary drummer Barry Altschul to take their place. The ensuing music’s angular themes and asymmetrical rhythms – driven by Altschul’s “from ragtime to no time” approach – regale with a swinging vitality rarely heard in Sharp’s prior work, resulting in the most accessible recording of his career thus far.

Sharp finds stylistic concordance in Bynum and Green’s vanguard company, parlaying brassy vocalizations with piercing altissimo refrains, multiphonic split-tones, wobbly pitch bends, and other extended techniques. Although possessing a singular style, Sharp’s bristling cadences and tonal manipulations on multiple horns (soprano and tenor saxophones, Bb and bass clarinets) are part of a longstanding lineage, ranging from the muscular linearity of Sonny Rollins to the un-tempered phrasing of Steve Lacy.

For all of Sharp and company’s colorful contributions, it’s Altschul’s gracefully abstract swing that defines the proceedings. Sharp’s intervallic writing for Aggregat favors manic, carnival-esque free bop, with sporadic interludes allotted for moody introspection, but Altschul’s unfettered zeal negotiating the no-man’s-land between inside and outside forms lends a unifying dimension to an otherwise varied set. Dialectrical is a remarkable accomplishment – not just for Sharp, but for Altschul as well.

–Troy Collins

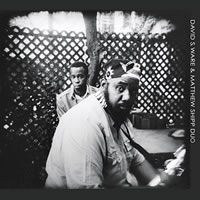

David S. Ware & Matthew Shipp Duo

Live in Sant’Anna Arresi, 2004

AUM Fidelity AUM 100 (DSW-ARC02)

Recorded in September of 2004 in Sardinia, Italy, Live in Sant’Anna Arresi is the second album in AUM Fidelity’s David S. Ware Archives series. Having performed with the other two members of the David S. Ware quartet a few days earlier, Ware and Matthew Shipp played a forty minute improvised duo set that is stunning in its urgency, vitality, virtuosity, and coherence as a large scale work. Throughout the pair feed and build off one another’s energy and creativity, taking turns leading, following, and working out ideas. At the time of the recording, Shipp had played with Ware for fifteen years, and this duo setting is ideal for witnessing their chemistry and dedication to shared musical goals.

Recorded in September of 2004 in Sardinia, Italy, Live in Sant’Anna Arresi is the second album in AUM Fidelity’s David S. Ware Archives series. Having performed with the other two members of the David S. Ware quartet a few days earlier, Ware and Matthew Shipp played a forty minute improvised duo set that is stunning in its urgency, vitality, virtuosity, and coherence as a large scale work. Throughout the pair feed and build off one another’s energy and creativity, taking turns leading, following, and working out ideas. At the time of the recording, Shipp had played with Ware for fifteen years, and this duo setting is ideal for witnessing their chemistry and dedication to shared musical goals.

As inspired as Ware’s playing is, what is perhaps more impressive is the key role Shipp plays in structuring the music. The way he reuses, reshapes, and returns to thematic, rhythmic, and motivic ideas and devices throughout binds the set while providing inspiration for Ware’s endless pursuit of the truth. Melodic fragments from Ware often appear verbatim or slightly modified in Shipp’s piano, sometimes a delightfully surprising twenty minutes after the fact. Other times he returns to a quasi-walking bass left hand that spurs Ware in new directions that gives him a new context to explore. Perhaps the best example of Shipp’s architectural and formal sensibilities is his use of steadily repeating block chords that he deploys and revises in different tempos, ranges, and dynamic levels throughout the performance. The album’s brightest moment stems from this repeated chord foundation. A quarter through the set, as the duo begins to really lock in, Shipp settles into an eighth note pattern of block chords that shift harmony every four beats, while Ware moves from his cascading sheets of sound runs into longer held, sonorous high notes. One gets the feeling the duo had found the path to discovering a deep profundity, and as they transitioned from that episode to the next the audience applauds, knowing it had witnessed something special.

As Shipp explains in the liner notes, on this recording the listener experiences “the intersection of the world of David S. Ware and the world of Matthew Shipp, as I go in and out of what my role might be within David’s music and what I might do in my own universe.” The listener gets an additional peek into this dynamic during the performance’s brief encore, in which Ware and Shipp trade a series of short solos that further flesh out the contours of their singular, yet complimentary worlds. One can only hope that the further installments of the David S. Ware Archives series will continue to add to our understanding of Ware’s life and his significant contribution to the music.

—Chris Robinson