A Fickle Sonance

a column by

Art Lange

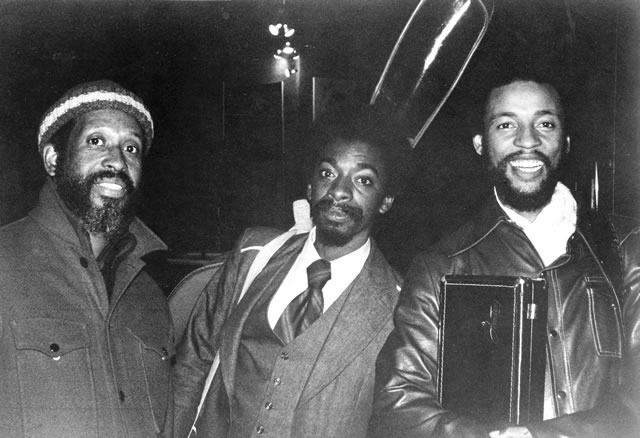

Air: Steve McCall, Fred Hopkins + Henry Threadgill Bobby Kingsley©2010

Retrospectives aren’t what they used to be. In the past, it seemed that only deceased visual artists who had achieved an unassailable, critically validated stature received a career retrospective exhibition from a suitably authoritative museum. These days, in an interesting Catch-22, living artists are frequently certified by the recognition of a retrospective itself – that is, having one makes the artist famous enough to have one. Nevertheless, what’s most important is that the size and scope of the retrospective present the opportunity for a reassessment of their work. Seeing so much art at one time and in one place can be an overwhelming experience, and may revitalize an artist’s reputation – or damage it, if works of lesser quality, necessarily included for the sake of completeness and historical veracity, negatively affect our perception of the artist’s abilities. In a similar way, volumes of usually posthumous “collected” poetry inevitably mix the commonplace in with the greatest hits, for better or worse, and risk suffering neglect for the sheer bulk, if not the unevenness, of their contents. But for the obsessively curious or the compulsively acquisitive, too much is never enough. (I willingly put myself in the former category, but only admit to the latter in special circumstances.)

I suppose the musical equivalent of the career retrospective or collected edition is, in some ways, the ever-more-ubiquitous box set. There are times when “completeness” makes perfect conceptual sense – having all of the Hot Five and Seven recordings together in one place, or compiling all of Robert Johnson’s once-rare recordings, or even, as I’ve recently seen, issuing a box containing all of the otherwise unrelated performances on which the late, apparently now cult saxophonist Joe Maini takes a solo. Not that everyone is, or even should be, interested in hearing every solo Joe Maini ever recorded, but it’s amusing to know it’s there if you want to. On the other hand, completeness for its own sake can be bewildering or obscuring or simply redundant (unless you’re a scholar or one of those aforementioned obsessives) – and yet labels continue to pump out box after box padded with mediocre material from deserving and perhaps-not-so-deserving artists alike, for the sake of completeness. Will there be time enough in the afterlife to finally scrutinize and appreciate the difference between Blind Blake’s alternate takes? Does anyone other than a blood relative feel the need to listen to more than maybe a half-dozen Phil Woods albums? Is there a market for The Complete Conte Candoli?

Which is why it’s such a pleasure to experience a collection that does what a retrospective should do – not only serve to illuminate a valuable portion of a significant career, but also restore to availability long out of print material, and allow us to reconsider some brilliant music from a fresh perspective. The Complete Novus & Columbia Recordings of Henry Threadgill & Air (Mosaic), eight CDs documenting five diverse groups and 18 years of impressive activity, does all that, and more. Alas, ironically, it’s not as complete as one might have hoped. Four of Threadgill’s groups represented here recorded for several labels between 1975 and 1996, including some with which Mosaic does not have contractual agreements. Thus the lack of Air’s first three albums (Air Song, Air Raid, and Air Time), the first three recordings of Threadgill’s Sextet(t) (When Was That?, Just The Facts And Pass The Bucket, and Subject To Change), Very Very Circus’ initial three releases (Spirit Of Nuff…Nuff, Live At Koncepts,and Too Much Sugar For A Dime) and the recording that bridged the gap between Very Very Circus and Make a Move (Song Out Of My Trees) – fine music, of course, and certainly necessary to see how Threadgill devised and developed his individual concepts for each varied ensemble. In effect, however, this means that the Mosaic collection presents each group in full maturity, and still gives us an overview of Threadgill’s evolving artistry during two crucial decades. Most importantly, as Spencer Tracy, with an exaggerated New York dialect, said of Katherine Hepburn in Pat & Mike, “What there is, is cherce.”

Though a canny and penetrating improviser on all sizes of saxophones and flutes, Threadgill’s most innovative and boldly expressive ideas are found in his compositions. His primary roots may lie in Swing, blues, and the evangelistic fervor of the Church of God (his early experiences are documented in George Lewis’ history of the AACM, A Power Stronger Than Itself), but the endearing qualities of his compositions emerge in the idiosyncratic ways he adopts and transforms a world-view of musical resources. Threadgill has traveled widely – to Southeast Asia due to his service in the Army, India, the Caribbean, and South America by choice – and is no doubt a voracious listener; while no single influence ever takes precedence, multiple threads are woven deeply and almost indiscernibly throughout his scores. For example, in Air, the cooperative trio with bassist Fred Hopkins and drummer Steve McCall that arose out of experiences with the AACM, the three musicians – each one a shrewd manipulator of rhythm and tone – layered individual responses to the given material in complex horizontal patterns and gradual modulations that sometimes resembled the linear design of Indian ragas; the percussion hubkaphone, which Threadgill introduced at this time, was a portable one-man Balinese gamelan. Nearly twenty years later, in seguing from Very Very Circus to the Make a Move band, he imported a Venezuelan drummer and vocalist, South African accordionist, Chinese pipa (lute) player, and occasionally added harpsichord or hunting horns to his already unorthodox instrumental palette, blending them together into surreal stylistic dramas.

While Air was a largely improvisatory and structurally interactive ensemble, it nevertheless set Threadgill on a compositional path with twists and diversions he would gleefully explore in the coming years. Open Air Suit and the live performances of Montreux Suisse Air revel in group maneuvers – asymmetric syncopations, shifting realignments of motives and timbres, multiple narratives – that impact the music’s form. But in retrospect, Air Lore, with its remarkable time-warp adaptations of a pair of pieces each by Jelly Roll Morton and Scott Joplin, shows even more clearly how the band’s elasticity of phrasing, episodic tempos, redefining of details (like Hopkins’ modernized bass lines), and, especially, emphasis on the contrasting character of multi-sectional forms would be put to good use by Threadgill in compositions to come.

The session-and-a-half recorded under the title X-75, in 1979, was a brief interlude where Threadgill was able to apply his most advanced concepts. The unusual ensemble – four flutes or saxophones, four basses, and voice – had orchestral implications far beyond Air’s compact, limited sonorities, capable of suggesting Bartokian melodic contours and microtonality in the basses, Japanese vocalese, and Varèse (“Density 21.5”) and Debussy (“Syrinx”), as well as shakuhachi qualities, in the flutes. Of the three previously unreleased performances, “Luap Nosebor” (which sounds like typical Threadgillian wordplay, but is a serious dedication to Paul Robeson) is a densely knit, classically contoured piece, but “Salute to the Enema Bandit,” with its driving rhythm and forceful ensemble, points the way to his next, more versatile band.

The fact that the Henry Threadgill Sextet and David Murray’s Octet appeared within a year of each other in the early ‘80s, and moreover that Threadgill participated in the Murray Octet’s first three recordings, cannot be a coincidence; nor is their mutual debt to the sound and rigorous nature of the mid-‘60s midsized groups (six to eight pieces) that Archie Shepp led on Four For Trane, Fire Music, Mama Too Tight,and The Way Ahead – albums notable for their intensity and eclecticism, covering hard-edged post-bop, free polyphony, r&b, Ellingtonian romanticism, and even tongue-in-cheek bossa nova. Threadgill claimed he thought of the Sextett – the second “t” was added when the band switched labels from About Time to RCA Novus in ’86 – in terms of instrumental sections, but the variety of styles which he put it through required the flexibility of a theater pit band, the rough spirit of King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band or a Charles Mingus combo, and the sensitivity and colors of a chamber ensemble.

During this period Threadgill’s compositions blossomed, as the three albums included here attest. From this point on, Threadgill is crafting tone poems – works of unconventional form, vibrant colors, and dramatic moods – not in the Richard Strauss programmatic, bloated manner (Strauss once boasted he could describe a fork with music), but alternately robust, nimble, seductive, or introspective multi-sectional mini-dramas. The breadth of detail and design are exhilarating: fanfares, horns as backing choirs, counter-themes, episodes of contrasting character or tempos, rhythmic shifts (from rollicking New Orleans struts to suave Latin tinges to joyfully lilting romps), unpredictable melodic contours, and solos that do not divert attention from the composition, but refocus and intensify it. Threadgill carried over this tone poem sensibility to subsequent groups, albeit with newly circumscribed tonal qualities. For a while this meant the twin guitars and twin tubas (plus trombone or french horn and Threadgill’s reeds) of Very Very Circus. The tracks on Carry The Day and Makin’ A Move exhibit the band’s airy textures, taut rhythms, and crisp, chiming, chugging, choogling foundation. But by the time Very Very Circus signed with Columbia, Threadgill was already expanding the band’s colors and personality with guests, inventing pieces for guitar quartets, cello trios, and combinations thereof, watching it gradually morph into the smaller but equally evocative Make a Move.

Henry Threadgill has a unique, restless compositional vision, and an equally novel sense of language – witness the care and cleverness he devotes to his titles. Certain themes repeat, as do mysterious motifs in his music – enigmatic references or allusions to death and sex, food and flowers, are common, and people seem to reappear in different guises – there’s Trinity (whom Threadgill apparently identifies with), and the Jenkins Boys, the Dodge Boys, the Enema Bandit, Sir Simpleton, and “Those Who Eat Cookies.” Puns and poetic descriptions abound. Are they meant to be clues, or conundrums? Certainly, the rags (“Off the Rag” and “Sweet Holy Rag”) from Rag, Bush And All reflect back on the early, meaningful influence of Morton and Joplin, and there is the possibility of reading the titles as sexual slang, but keep in mind “to rag” is also to scold or make fun of, so is this a subtle, satiric political comment on George Bush the First? (The album was recorded just a month after his election in 1988.) “The Devil Is On the Loose and Dancin’ With a Monkey,” indeed. This is why we need retrospectives like this, to take a closer look at what we thought we knew, hopefully understand it better and appreciate it all the more the second time around.

Art Lange©2010