Moment's Notice

Recent CDs Briefly Reviewed

(continued)

Anthony Braxton

Piano Music (1968-2000)

Leo 901-909

Surveying Anthony Braxton’s scored music for piano is not like tackling the repertoire of Bach, or Beethoven, or even Schönberg for that matter; the breadth of stylistic considerations, notational complexities, and interpretive options requires not only technical command but a philosophical and conceptual commitment to what the composer calls “idea formation.” That is to say, seldom does he provide the pianist with a score simply to be followed; for the most part, these are like maps which display the details of the musical landscape, but it is up to the performer to chart a course that is faithful to the nature of the sounds and illuminates the spirit of the journey. In the booklet accompanying this lavish nine-CD package, Braxton praises pianist Geneviève Foccroulle’s “strategies of time and material integration,” and it is to her credit that her strategic vision of Braxton’s challenging music allows each work to express its own character while suggesting evocative associations and analogies.

Surveying Anthony Braxton’s scored music for piano is not like tackling the repertoire of Bach, or Beethoven, or even Schönberg for that matter; the breadth of stylistic considerations, notational complexities, and interpretive options requires not only technical command but a philosophical and conceptual commitment to what the composer calls “idea formation.” That is to say, seldom does he provide the pianist with a score simply to be followed; for the most part, these are like maps which display the details of the musical landscape, but it is up to the performer to chart a course that is faithful to the nature of the sounds and illuminates the spirit of the journey. In the booklet accompanying this lavish nine-CD package, Braxton praises pianist Geneviève Foccroulle’s “strategies of time and material integration,” and it is to her credit that her strategic vision of Braxton’s challenging music allows each work to express its own character while suggesting evocative associations and analogies.

Of the twelve selections featured here, eight were previously recorded by Hildegard Kleeb in a four-CD set released in the hat Now Series in 1996. Foccroulle adds Composition No. 301 and the multimedia Composition No. 171, as well as a second version of Composition No. 32, and an hour-long collage she derived (with Braxton’s approval) from sections of Compositions No. 30-33, entitled The Trip. She omits Composition No. 16, a graphic score for four pianos, which Kleeb included. As I wrote the program notes for that hat Now release, a potential conflict of interest prevents me from a critical comparison of the two. However, I can say that the interpretive differences between them are significant and easily audible, and the choices that each makes in constructing a performance with Braxton’s material inevitably offer varying details and in some cases a radically distinct perspective – the most obvious examples are Foccroulle’s version of Composition No. 33, which at 42 minutes is twice as long as Kleeb’s, and Composition No. 31, which Kleeb performs in 52 minutes, while Foccroulle takes 36. Braxton is fortunate to have two such conscientious and creative interpreters of this music.

The earliest of the pieces, Compositions No. 1 and No. 5, are, with only minor exceptions, precisely notated, reflecting Braxton’s enthusiasm for Stockhausen and Webern, and Foccroulle plays them with accuracy and an ear for dynamic variety and lyrical flow. The other two fully notated works, Compositions No. 139 and No. 301, are related in Braxton’s mind as alternatives to the strict requirements of post-Schönberg serial processes, so his predetermined motifs are intuitively redesigned and reorganized with an emphasis not on systematic order, but extended melodic continuity. Especially in Composition No. 301, Foccroulle’s varied touch affects the color and intensity of the music, from the biting angularity of line that begins the work to the crisp interaction of bass notes and treble phrases that sustains momentum. Her approach to this nearly-forty minute work brought to mind the Piano Sonata (1952) of Jean Barraqué, a composition of similar scope and syntax, which also sought a reconciliation between systematic and intuitive form and what Paul Griffiths called “pulsed” and “pulseless” rhythms.

Foccroulle’s account of the dense, indeterminate “Paris” compositions – Nos. 30-33 – highlight their dramatic differences. She uncovers a subtle blues feeling in the scurrying figures and amusing twists of line in Composition No. 30, and though her staggered phrasing implies both Monk and the syncopations of ragtime, it’s a bit too crisp and reserved to say it swings. In No. 31 she takes a firmer, more aggressive “New Music” tact, but at the same time her varied rhythmic sensitivity brings a bright wit to the relationship of parts. In her hands, No. 32 becomes a firestorm, with hazy echoes and overtones due to Braxton’s indication of the pedal throughout. And her calm, delicate, deliberate depiction of No. 33’s forest of chords gives the music a contemplative mood and sustained frame of reference that recalls not only Morton Feldman, but the mystical, Rosicrucian-inspired works of Erik Satie. (There are similar associations in The Trip, where her chording draws out Messiaenic parallels.)

The longest and most unconventional work is Composition No. 171, conceived for a pianist who has to negotiate a dense, repetitious sequence of motifs and simultaneously recite a complicated, tongue-in-cheek parody of a press conference by a Park Ranger of the future, plus four actors, four prompters, and three projection screens. Without the actors and images, full responsibility falls onto Foccroulle, and her juggling of musical and theatrical roles is remarkable. The text, a blend of touristy ad jargon and Braxton’s scholarly description of his process, is downright funny at times, and also ironically revealing: “The melody is there if you want it,” “Quick changes of mind and/or inspiration are at the heart of the system,” and “Who would have believed it could be possible to wipe out the hopes of a new generation so easily.” The music, using ostinatos and blunt, motoristic patterns that Braxton normally eschews, may be a parody as well, representing a symbolic tripartite system (of government?) that “rarely agrees on anything.” In this non-theatrical format the work has its moments, but at nearly two hours long, and lacking the visual component, the concept seems stretched beyond its limit.

Though this collection may not introduce any new chapters, it is a valuable and often insightful extension of the Braxton canon—challenging, unpredictable, and rewarding as ever.

-Art Lange

Anthony Braxton

Trio (Victoriaville) 2007

Victo cd 108

12tet + 1 (Victoriaville) 2007

Victo cd 109

Nine Compositions (DVD) 2003

Rastascan BRD 060

Ten years ago, a wag predicted that, eventually, everyone – literally everyone – will release a recording by Anthony Braxton. Though this has yet to come to pass, the good will and enthusiasm Braxton and his music creates is manifest in the bushel basket of CDs released each season by an ever-growing roster of labels. What continues to separate Braxton from other obsessively documented artists is that each bulk addition to Braxton’s behemoth discography constitutes a viable chapter of an ongoing saga, in which various narrative threads are extended and entwined with others, occasionally producing pungent twists. These recordings meet this threshold: There is the echo of Braxton’s mid-‘70s trio with Leo Smith and Richard Teitelbaum in the FIMAV performance of Diamond Curtain Wall Trio, and the Rastacan collection has an element of the prodigal professor’s return, given how the Bay Area community rallied about Braxton during his life-pivoting tenure at Mills College..

Ten years ago, a wag predicted that, eventually, everyone – literally everyone – will release a recording by Anthony Braxton. Though this has yet to come to pass, the good will and enthusiasm Braxton and his music creates is manifest in the bushel basket of CDs released each season by an ever-growing roster of labels. What continues to separate Braxton from other obsessively documented artists is that each bulk addition to Braxton’s behemoth discography constitutes a viable chapter of an ongoing saga, in which various narrative threads are extended and entwined with others, occasionally producing pungent twists. These recordings meet this threshold: There is the echo of Braxton’s mid-‘70s trio with Leo Smith and Richard Teitelbaum in the FIMAV performance of Diamond Curtain Wall Trio, and the Rastacan collection has an element of the prodigal professor’s return, given how the Bay Area community rallied about Braxton during his life-pivoting tenure at Mills College..

What further distinguishes this passel of Braxton recordings is that the either/or choices for recession-wracked consumers are tougher than usual. If one of this threesome would be prone to be lost in the crowd by size-matters, marquee value-minded buyers, it would be Trio (Victoriaville) 2007; though cornetist Taylor Ho Bynum and guitarist Mary Halvorson are integral to Braxton’s music in this period, they are still in ascent. Yet, bypassing this hour-long performance of “Composition No. 323c” would leave a substantial gap in the understanding of Braxton’s current music and where it very well may be going for some time to come. The Diamond Curtain Wall Compositions introduce interactive computer technology into Braxton’s ongoing project of structuring improvisation; it is an element that is well-suited for this trio, as each member has quick, yet subtle reflexes, and wields their own arsenal of sounds. Bynum and Halvorson have a strong feel for both phrase-based and textural materials that are specific and thought-provoking, but do not saturate the moment, a balance more desirable than usual given the unpredictability of the Braxton-programmed SuperCollider materials – it is noteworthy that when the musicians feel the piece has concluded and have ceased, the laptop throws down a final, unaccompanied burst that abruptly quiets to a tenuous tone. The fine rapport that Bynum has with Braxton in improvised space is continued here; but, arguably, it is Halvorson’s dovetailing of Braxton’s sweeping alto lines near the end of the piece that is the performance’s most inspired example of close listening. Throughout the piece, Halvorson demonstrates a smart, free-wheeling approach to tactics codified by Bailey, Frith and others; however, it is her ability to not only key into other players instantly, but to intuit their next several steps that is at the crux of several of the performance’s highlights. Braxton’s own playing is incisive; several passages are absolutely ferocious while several more are piquantly lyrical. His incorporation of six saxophones spanning the sopranino to the contrabass is nothing less than masterful, with each change of instrument shading the music and nudging it into a new direction. As a result, Trio (Victoriaville) 2007 withstands comparison to the Braxton-Smith-Teitelbaum summit on the Sackville classic, Trio and Duet.

The concurrent release of 12+1tet (Victoriaville) 2007 and the audio-only Nine Compositions (DVD) 2003 – a brilliant use of the DVD format that crams six hours of music onto a single disc without any degradation in fidelity – offers insights into how the history and regional flavor of an experimental music community can shape malleable compositions like Braxton’s. The Bay Area musicians who work on an ongoing, if occasional basis with Braxton are an edgy DIY lot. This has been reflected in interpretations of Braxton’s music reaching back to Splatter Trio’s co-op recording with Debris, Jump or Die (1992; Music & Arts), and even further to Rova’s collaboration with Braxton, The Aggregate (1988; Sound Aspects), and Braxton’s Duet 1987 with percussionist and Rastacan founder Gino Robair, interpretations predicated on an earlier image of Braxton, the unflinching trailblazer rather than the avuncular professor. This hard-core stance is also abundantly present on more recent Rastacan recordings like Six Compositions (GTM) 2001 and projects like guitarist John Shiurba’s 5 x 5. So, it is not surprising, even though 12+1tet members Bynum, tuba player Jay Rozen and bassoonist Sara Schoenbeck are on the date, that Nine Compositions has a defiant, stinging energy that stands in contrast to the FIMAV performance. Robair is arguably the epicenter of this energy; a percussionist who uses a blunt attack and clangor with surgical precision, Robair is an agitator rather than an accompanist, as evidenced in the collection’s four large ensemble works and the three trios with Braxton and Shiurba (the latter pieces, notably, date from the 1970s). With Six Compositions veterans like Shiurba and saxophonist Scott Rosenberg scattered through the ensemble, there’s real grit in the scored passages of the large ensemble pieces (compositions numbered “328,” 327,” “322,” “292,” and “195”). The absence of full-time flutist, violinist and bassist, as well as an increased high brass presence established by Bynum and trumpeters Liz Allbee and Greg Kelley, contributes to the ensemble’s rousing, jabbing attack. The woodwind section, rounded out by Ma++ Ingalls, Don Plonsey and Justin Wang – double-reed specialist Kyle Bruckman also plays on one large ensemble performance and two tracks for small horn groups – earnestly buttress the scored passages, and repeatedly generate sparks when the piece grants them latitude. This is an ensemble that honors the maverick audacity of Braxton’s music.

Even though the Victo performance occurred more than a year after the 12+1tet performances that yielded the still-staggering Firehouse 12 box set, this reading of “Composition No. 361” feels like a direct continuation of the earlier work. The Iridium stand gave the 12+1tet comprehensive operational knowledge of Braxton’s daunting conventionally notated scores, his graphic notation and cueing systems; subsequently, this performance exudes a relaxed confidence that can be misheard as mere polish. Not surprising, given that several of Braxton’s most steadfast cohorts of the past decade are on board, including Bynum and saxophonists James Fei and Steve Lehman. The diverse colors in the 12+1tet’s palette make an almost continuous impact, beginning with violist Jessica Pavone’s soaring solo following the ensemble’s opening salvo. Even though Pavone and flutist Nicole Mitchell make substantial individual contributions, their pull on the ensemble sound is equally important; they, along with bassist Carl Testa, give Schoenbeck in particular a warmer spectrum of colors into which to integrate. Something of the same can be said of trombonist Reut Regev and Rozen, who create a burnished low brass mass in several passages. A much fuller orchestral sound is the result, one that makes the saxophone-dominated early GTM ensembles sound comparatively two-dimensional. Yet, the real benefit of this configuration is realized when sub-groups emerge, improvised elements seep into the foreground and the protean nature of Braxton’s concepts are clearly audible. The combinations of possible colors are multiplied by the number of multi-instrumentalists in the ensemble – Halvorson is the only musician playing just one instrument. The changes resulting from one musician changing his or her instrument can be pronounced, as is the case when Aaron Siegel switches between the drum kit and the vibraphone, or subtle, as is the case when Andrew Raffo Dewar slips between clarinet, and C melody and soprano saxophones. Regardless, each shift steams the pace, which is no small consideration given Braxton’s mandate of hour-long performances of his current compositions. With everyone – including a conspicuously inspired Braxton – generating engaging material, 12tet + 1 (Victoriaville) 2007 is a sterling example of how Braxton’s music system equally accommodates the individual and the collective.

-Bill Shoemaker

Rob Brown Ensemble

Crown Trunk Root Funk

AUM Fidelity AUM044

It is almost twenty years since Rob Brown made his debut as leader with the Silkheart release Breathe Rhyme. It introduced a fiery, tempestuous player whose saxophone lines were nonetheless impressively liquid and clearly enunciated, distinguishing Brown at once from a whole raft of soapbox altoists in an approximately post-Ornette freebop mode.

It is almost twenty years since Rob Brown made his debut as leader with the Silkheart release Breathe Rhyme. It introduced a fiery, tempestuous player whose saxophone lines were nonetheless impressively liquid and clearly enunciated, distinguishing Brown at once from a whole raft of soapbox altoists in an approximately post-Ornette freebop mode.

The recorded output under his name has been patchy since then, with discs tending to come in small clusters with sizeable gaps in between, a not uncommon situation but one that quickly undermines any whiggish desire to trace a path of “development” or “evolution”. The sophomore disc, High Wire for Soul Note, was precisely that, suggesting strongly that while Brown had his chops in order his compositional skills either hadn’t advanced in the seven year gap between the two releases (though only four between the recordings) or else Brown didn’t regard written form as unduly important.

He’s touched down for a variety of labels since – Music & Arts, Bleu Regard, Riti, CIMP, Rogue Art, Marge, Clean Feed, No More – and apart from the last of these he hasn’t, to my knowledge, made more than one record for any imprint; again, not unusual, but not necessarily a positive tack for a player. Aum Fidelity’s Steven Joerg could be the making of him. This is a beautifully shaped and presented set, the themes mostly based round simple ostinati set up by pianist Craig Taborn (who adds electronic washes and glitter here and there), bassist William Parker and drummer Gerald Cleaver.

The meters are mostly relatively simple, though the subtle rhythmic slippage of “Ghost Dog” is characteristic. Brown still doesn’t run to long-lined themes, but worries at modest melodic material with a concentration that sometimes suggests Ornette, sometimes Jimmy Lyons, though I strongly suspect you might also find some old Paul Desmond vinyl in his private collection, alongside a slew of Jackie McLean Blue Notes; there’s something of Jackie’s ever-so-slightly sharp blues wail on some of the higher register lines, though as he shows on “Ghost Dog” again, Brown moves comfortably into a lower register with little sense of a break. He does something similar on the opening “Rocking Horse”, but there throws in some uncharacteristically tentative trills and abstract patterns that don’t add much to the track and only serve to divert attention to what Taborn and Cleaver are doing underneath.

As far back as High Wire, Brown had formed the notion that Parker was the right bassist for his music. I’ve long been skeptical, not so much about William’s skills and vision, which are unquestionable though possibly now both over-rated and –exposed, but rather about his suitability to Brown’s overall sound. Listening back through the records where he appears, you get a strong sense that what’s needed is either an Izenzon who can sing underneath the alto lead or else a Fred Hopkins or Malachi Favors who could bring a die-stamped authority to the line as well as lyricism. Parker’s rumbles sound sententious here and on “Clearly Speaking” he fails to do that, for all Glen Forrest and Michael Marciano’s efforts to sharpen him up in the mix; I’ve noticed this before – attempt to tweak Parker or foreground him, and he sounds even more recessed and muffled.

Otherwise, it’s a formidable group. Taborn is most interesting the simpler he plays, and his longish statement on “Rocking Horse” is shaped out of a rag-picker’s strips of melody. “Clearly Speaking” is perhaps Brown’s strongest moment, a wonderfully shaped and highly effective solo statement. Listen to it twice, though, and what jumps it is Cleaver’s magnificent work behind. For me, he’s a more compelling figure than the equally over-exposed Hamid Drake, and this is among his best showings on record.

“Sonic Echosystem” is overlong for its relatively slight substance, and there’s a sense of ideas being retreaded over the final fifteen minutes, but that’s just a way of wheeling on a familiar beef about duration. At all but an hour, Crown Trunk Root Funk isn’t exactly stretched by present standards, but it would have gained more than lost from the shedding of one track. That said, it’s probably Brown’s most compelling disc to date and one hopes the start of a longer association that will allow him to develop the kind of sympathetic studio sound his work surely merits.

-Brian Morton

By Any Means

Live at Crescendo

Ayler aylCD-077/078

Given the trio is comprised of Fire Music and Ecstatic Jazz icons Rashied Ali, Charles Gayle and William Parker, By Any Means is remarkably rooted in blues, motif-driven heads and otherwise thematically based pieces on this 2-disc set. However, this does not dampen their intensity. If anything, the materials give Gayle well-grounded lenses through which his fiercely braying alto burns with precision, bringing his fluent use of bop and blues idioms into sharper focus than usual. This gives both Ali and Parker enough leeway to modulate the feel, but without stretching the materials or the form of a given piece beyond recognition. Ali and Parker’s respective dexterity in shifting accents allows them to repeatedly move the pocket, spiking the voltage of even Gayle’s most generic phrases, while supplying a tether for the saxophonist’s most explosive outbound flights. In addition to their percolating duo exchanges, both Ali and Parker take full advantage of the ample available solo space. Parker’s solos are, as usual, beguiling, even if they are constructed from familiar mixes of skittering and moaning arco passages and tuneful and propulsive pizzicato lines. Intriguingly, Ali doesn’t solo to stereotype, often employing both a lighter than expected touch and rudimentary materials, which solders his connection to the modern jazz drumming tradition he allegedly atomized with Coltrane. For that matter, Gayle does much of the same when he barrels through blues choruses. This tendency is at the crux of why By Any Means is a group that lives up to its name.

Given the trio is comprised of Fire Music and Ecstatic Jazz icons Rashied Ali, Charles Gayle and William Parker, By Any Means is remarkably rooted in blues, motif-driven heads and otherwise thematically based pieces on this 2-disc set. However, this does not dampen their intensity. If anything, the materials give Gayle well-grounded lenses through which his fiercely braying alto burns with precision, bringing his fluent use of bop and blues idioms into sharper focus than usual. This gives both Ali and Parker enough leeway to modulate the feel, but without stretching the materials or the form of a given piece beyond recognition. Ali and Parker’s respective dexterity in shifting accents allows them to repeatedly move the pocket, spiking the voltage of even Gayle’s most generic phrases, while supplying a tether for the saxophonist’s most explosive outbound flights. In addition to their percolating duo exchanges, both Ali and Parker take full advantage of the ample available solo space. Parker’s solos are, as usual, beguiling, even if they are constructed from familiar mixes of skittering and moaning arco passages and tuneful and propulsive pizzicato lines. Intriguingly, Ali doesn’t solo to stereotype, often employing both a lighter than expected touch and rudimentary materials, which solders his connection to the modern jazz drumming tradition he allegedly atomized with Coltrane. For that matter, Gayle does much of the same when he barrels through blues choruses. This tendency is at the crux of why By Any Means is a group that lives up to its name.

-Bill Shoemaker

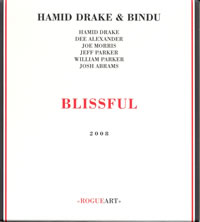

Hamid Drake & Bindu

Blissful

RogueArt ROG-0011

For nearly half a century, an important strain of avant garde jazz sees music-making as both a form of worship and a path to spiritual enlightenment. Hamid Drake’s new album is firmly in that tradition. Near the beginning, vocalist Dee Alexander sings, “Use any method of worship you please, or be free of method.” Under the circumstances, the line, from a book of Tantric verse in praise of the Hindu goddess Kali, applies equally well to worship and music. Through the centuries, Kali has been worshipped as a destructive deity, a mother-goddess, and a redeemer. Drake selects poems that address all these aspects of Kali so that the work converges in a vision of universal female spiritual energy. On “There Is Nothing Left but You,” he also invokes the names of female Santeria deities Yemaya and Ochun, and African American women liberators such as Harriet Tubman and Alice Coltrane as manifestations of this same spiritual power.

For nearly half a century, an important strain of avant garde jazz sees music-making as both a form of worship and a path to spiritual enlightenment. Hamid Drake’s new album is firmly in that tradition. Near the beginning, vocalist Dee Alexander sings, “Use any method of worship you please, or be free of method.” Under the circumstances, the line, from a book of Tantric verse in praise of the Hindu goddess Kali, applies equally well to worship and music. Through the centuries, Kali has been worshipped as a destructive deity, a mother-goddess, and a redeemer. Drake selects poems that address all these aspects of Kali so that the work converges in a vision of universal female spiritual energy. On “There Is Nothing Left but You,” he also invokes the names of female Santeria deities Yemaya and Ochun, and African American women liberators such as Harriet Tubman and Alice Coltrane as manifestations of this same spiritual power.

The music is of a piece with the spiritual vision. It draws on from Indian, African, and African American musical culture, and improvisation is the method which unites the sounds in a unified vision. The band, which includes guitarists Joe Morris and Jeff Parker and bassists Josh Abrams and William Parker re-enforces non-Western associations by doubling on African guimbri and doson ngoni, banjo (a descendant of the guimbri), Indian shenai, tabla, and bata drums. Alexander has a rich, gospel-tinged alto voice, with dark undertones and bright highlights and a fine command of extended techniques. Initially the instrumentals seem fraught with tensions, the texture of the shenai rasps against Parker’s rounded jazzy chords, Morris’s banjo cutting across the beat. But as Drake sets a tight, medium groove on “Playful Dance at Soma,” Morris’s thorny lines fit neatly into the weave of basses, Parker’s arco soars in a trio with Drake and Abrams and the band takes flight. The interlocking riffs and drum patterns on “Supreme Lady Victorious in Battle” and “There Is Nothing Left But You” generate escalating excitement that practically achieves levitation at times. The concluding “The Beautiful Names” is infused with genuine serenity and joy. This album is like one of Ellington’s Sacred Concerts, a very personal work that moves from a particular religious basis to a universal message. You don’t have to be a believer to get it.

-Ed Hazell