Moment's Notice

Recent CDs Briefly Reviewed

(continued)

Horace Silver

Live At Newport ‘58

Blue Note 50999 5 03163 2 8

Prior to this Newport Jazz Festival performance, which was unearthed at The Library of Congress in 2006, Horace Silver’s sole authorized live recording was Doin’ The Thing – At The Village Gate. This is incredibly odd, given that the ’61 Blue Note album demonstrated that the pianist’s well-hooked themes and tangy grooves were perfectly suited for the club date format. It is a gambit Silver could have easily returned to time and again through the ‘60s, probably with a commercial success comparable to Cannonball Adderley’s hit-spawning live albums – which were largely studio sessions with a civilian audience.

Prior to this Newport Jazz Festival performance, which was unearthed at The Library of Congress in 2006, Horace Silver’s sole authorized live recording was Doin’ The Thing – At The Village Gate. This is incredibly odd, given that the ’61 Blue Note album demonstrated that the pianist’s well-hooked themes and tangy grooves were perfectly suited for the club date format. It is a gambit Silver could have easily returned to time and again through the ‘60s, probably with a commercial success comparable to Cannonball Adderley’s hit-spawning live albums – which were largely studio sessions with a civilian audience.

This set catalogs the funk-laden seeds of Silver’s hard bop that flowered with the rise of soul jazz. “Señor Blues,” first recorded in ’56 for Six Pieces of Silver, was already a Silver standard, a smart blending of a catchy piano and bass figure in Latinate 6/8 and a beguilingly simple, bluesy theme. A historical footnote: “Señor Blues” had been rerecorded with vocalist Bill Henderson just prior to Newport for release as a 45rpm single. The flip side was “Tippin’,” which Silver called to open the Newport set; a flowing, if somewhat generic line, it nevertheless is brimming with the bright, crowd-pleasing swing that was fundamental to Silver’s brand of hard bop The set is rounded out by two of the best examples of how Silver made unorthodox structures swing, “The Outlaw,” and “Cool Eyes.” The latter was a classic opener on Six Pieces of Silver; here, it’s an equally effective closer. Credit Silver’s stealth of dispensing with the composition’s ABCD structure for a “Rhythm” changes variant to accommodate the soloists. Recorded six months before Newport for the soon-to-be-reissued Further Explorations, “The Outlaw” changes its rhythmic feel a half dozen times a chorus; but, then, they are very long, irregularly sub-divided choruses. Each time the rhythmic feel changes, it triggers a turn in the theme. But, the solos are buoyed by the type of ebullient grooves that Silver all but patented. Again, Silver was deft at airing out his composer chops, and then stepping back to let his band air theirs in the solos.

The definitive Silver Quintet was soon to jell with the arrival of trumpeter Blue Mitchell, which was precipitated by the imminent departure of Louis Smith, a stint so brief that Smith is not even mentioned in Silver’s autobiography. Yet, Smith’s presence at Newport confirms him to be both an excellent post-Brown stylist and the wrong guy for where Silver was taking his music. Smith was actually daring; he bucked convention on his ’57 Blue Note debut, Here Comes Louis Smith, by opening with almost a minute of blazing trumpet, accompanied only by drums. For a straight-up hard bop band, Smith’s erudition is magnetic; one really has to search no further for evidence of this than tenor saxophonist Junior Cook’s solos. Certainly, a measure of Cook’s hard-chargin’ performances is attributable to the setting, which suggests that Cook’s historical stock would have markedly benefited from at least occasional live recordings. Arguably, Cook is being tugged more towards a Mobleyesque stance on this occasion than would be the case when the tenor player, discovered by Silver at a DC rock and roll show, would team up with R&B journeyman Mitchell. With newly arrived bassist Gene Taylor and drummer Louis Hayes already totally in sync with the pianist, it is apparent that Smith was the odd man out, albeit an extremely talented one. Live At Newport ’58 is a snapshot of an excellent band one personnel change away from greatness.

–Bill Shoemaker

Stan Tracey + Keith Tippett

Supernova

ReSteamed.RSJ105

This is an absolutely stunning album. Pianists Stan Tracey and Keith Tippett were only occasional duet partners (they released just one prior LP on Emanem), but this previously unreleased 1977 concert from the ICA in London brims with vitality and uncanny rapport. Most impressive of all is the way they devote themselves so whole-heartedly to creating a single, unified piece of music together. They begin in close accord on “Veil Nebula,” with one keyboardist completing the gestures of the other, and build upward from there. But for long passages each develops independent, parallel lines that stand on their own, yet each part seems curiously well suited to the other. Everything is improvised, but every detail contributes to a composerly sense of form. Tippett initiates “Vela Pulsar,” the longest and most wide ranging of the duets, with notes cascading in the piano’s treble range, provoking similar star falls of notes from Tracey. Each part is both a fully realized music statement and a transitional bridge to the next part of the improvisation. There is a flowing gracefulness to every arpeggio and glowing trill. Soon massive chords build up clouds of overtones through which the pianists send arc of notes shooting and coiling. Then Tracey interjects some whimsical humor, sly little dissonant motifs that momentarily lighten the mood, but this soon gives way to a more solemn church-music feel. Blues and gospel blend into the music, which swells to a wildly energized, four-handed warped boogie-woogie. “Parallax” follows a more tightly focused path to a similarly ecstatic conclusion. Tracey opens with a lovely meandering line, which is answered in kind by Tippett. Tracey lobs out a contrasting short jittery riff and they exchange snippets of melody, establishing a rhythm that governs the music for a few minutes. Eventually they circle back to their initial intertwining lines gambit, pushing it to a thundering climax. “Supernova” opens with a grand chiming swirl – the bells of Debussy’s sunken cathedral caught in a crashing whirlpool – but the surge of chords and overtones breaks into a “Rite of Spring” frenzy of clashing note clusters and urgent rhythms before it ends. This is 45 minutes of breathtaking beauty and creativity. It can’t be recommended highly enough.

This is an absolutely stunning album. Pianists Stan Tracey and Keith Tippett were only occasional duet partners (they released just one prior LP on Emanem), but this previously unreleased 1977 concert from the ICA in London brims with vitality and uncanny rapport. Most impressive of all is the way they devote themselves so whole-heartedly to creating a single, unified piece of music together. They begin in close accord on “Veil Nebula,” with one keyboardist completing the gestures of the other, and build upward from there. But for long passages each develops independent, parallel lines that stand on their own, yet each part seems curiously well suited to the other. Everything is improvised, but every detail contributes to a composerly sense of form. Tippett initiates “Vela Pulsar,” the longest and most wide ranging of the duets, with notes cascading in the piano’s treble range, provoking similar star falls of notes from Tracey. Each part is both a fully realized music statement and a transitional bridge to the next part of the improvisation. There is a flowing gracefulness to every arpeggio and glowing trill. Soon massive chords build up clouds of overtones through which the pianists send arc of notes shooting and coiling. Then Tracey interjects some whimsical humor, sly little dissonant motifs that momentarily lighten the mood, but this soon gives way to a more solemn church-music feel. Blues and gospel blend into the music, which swells to a wildly energized, four-handed warped boogie-woogie. “Parallax” follows a more tightly focused path to a similarly ecstatic conclusion. Tracey opens with a lovely meandering line, which is answered in kind by Tippett. Tracey lobs out a contrasting short jittery riff and they exchange snippets of melody, establishing a rhythm that governs the music for a few minutes. Eventually they circle back to their initial intertwining lines gambit, pushing it to a thundering climax. “Supernova” opens with a grand chiming swirl – the bells of Debussy’s sunken cathedral caught in a crashing whirlpool – but the surge of chords and overtones breaks into a “Rite of Spring” frenzy of clashing note clusters and urgent rhythms before it ends. This is 45 minutes of breathtaking beauty and creativity. It can’t be recommended highly enough.

–Ed Hazell

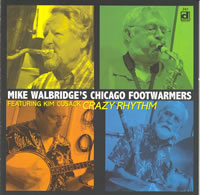

Mike Walbridge’s Chicago Footwarmers

Crazy Rhythm

Delmark 247

In traditional jazz, as in classical music, there are two primary theories of playing historical repertory. One is the “period instrument” approach, which dictates a recreation as close to the original performance as possible. The other is less rigidly authentic, and in the case of jazz ranges from reading transcriptions of the material while allowing new solos all the way to completely revised modern arrangements. The Chicago Footwarmers — named after a series of ad hoc small local bands that recorded in the ‘20s — have throughout their history adopted a comfortable middle tact, changing their instrumentation to suit the gig while maintaining a healthy respect, if not dogmatic reverence, for the style of music they play, which straddles ‘20s rollicking trad and ‘30s cozy swing. The irony of this release is that it combines the band’s first-ever recording, from 1966, and a new session featuring two of the founding members, tubaist Walbridge and undersung reedman Kim Cusack, recorded forty years later to the day.

In traditional jazz, as in classical music, there are two primary theories of playing historical repertory. One is the “period instrument” approach, which dictates a recreation as close to the original performance as possible. The other is less rigidly authentic, and in the case of jazz ranges from reading transcriptions of the material while allowing new solos all the way to completely revised modern arrangements. The Chicago Footwarmers — named after a series of ad hoc small local bands that recorded in the ‘20s — have throughout their history adopted a comfortable middle tact, changing their instrumentation to suit the gig while maintaining a healthy respect, if not dogmatic reverence, for the style of music they play, which straddles ‘20s rollicking trad and ‘30s cozy swing. The irony of this release is that it combines the band’s first-ever recording, from 1966, and a new session featuring two of the founding members, tubaist Walbridge and undersung reedman Kim Cusack, recorded forty years later to the day.

The initial edition of the band alternated between quartet and quintet (adding Johnny Cooper’s piano), notable for the flexible role of Walbridge’s tuba, which provided propellant bass lines but also slipped into the front line to engage Cusack’s clarinet or alto saxophone. Without cornet or trombone in the band, there was plenty of elbow-room for Cusack to flit in and out of synch with the rhythm section; his clarinet in a more active, lyrical Chicago mode (a la Pee Wee Russell without the exaggerations) than down home New Orleans style, and his alto sax rooted in the ‘20s, unbeholden to the influence of Benny Carter or Johnny Hodges. Walbridge’s facility was and is remarkable, offering fluid melodies on the likes of “Crazy Rhythm” and turning robust on “Big Butter and Egg Man.” “Nagasaki,” composed long before the bombing which brought the city to the world’s attention, is a great piece of hot jazz. The only problem with this early program is the relentless (albeit prevalent at the time) on-the-beat banjo. For the recent session, however, the late Lynch was replaced by Don Stiernberg who, in addition to prickly banjo solos, plays guitar on several of the tracks, contributing to the quartet’s smoother, mellow ensemble. Not attempting to mimic their old sound, the rhythm section here (with Bob Cousins on drums) has a subtlety all the more appropriate for Cusack’s flow of tasteful, occasionally tart, ideas on “I Never Knew” or the extended, unorthodox “Tin Roof Blues.” Walbridge, meanwhile, has lost none of his prowess or enthusiasm. It’s a fine band, then and now.

–Art Lange